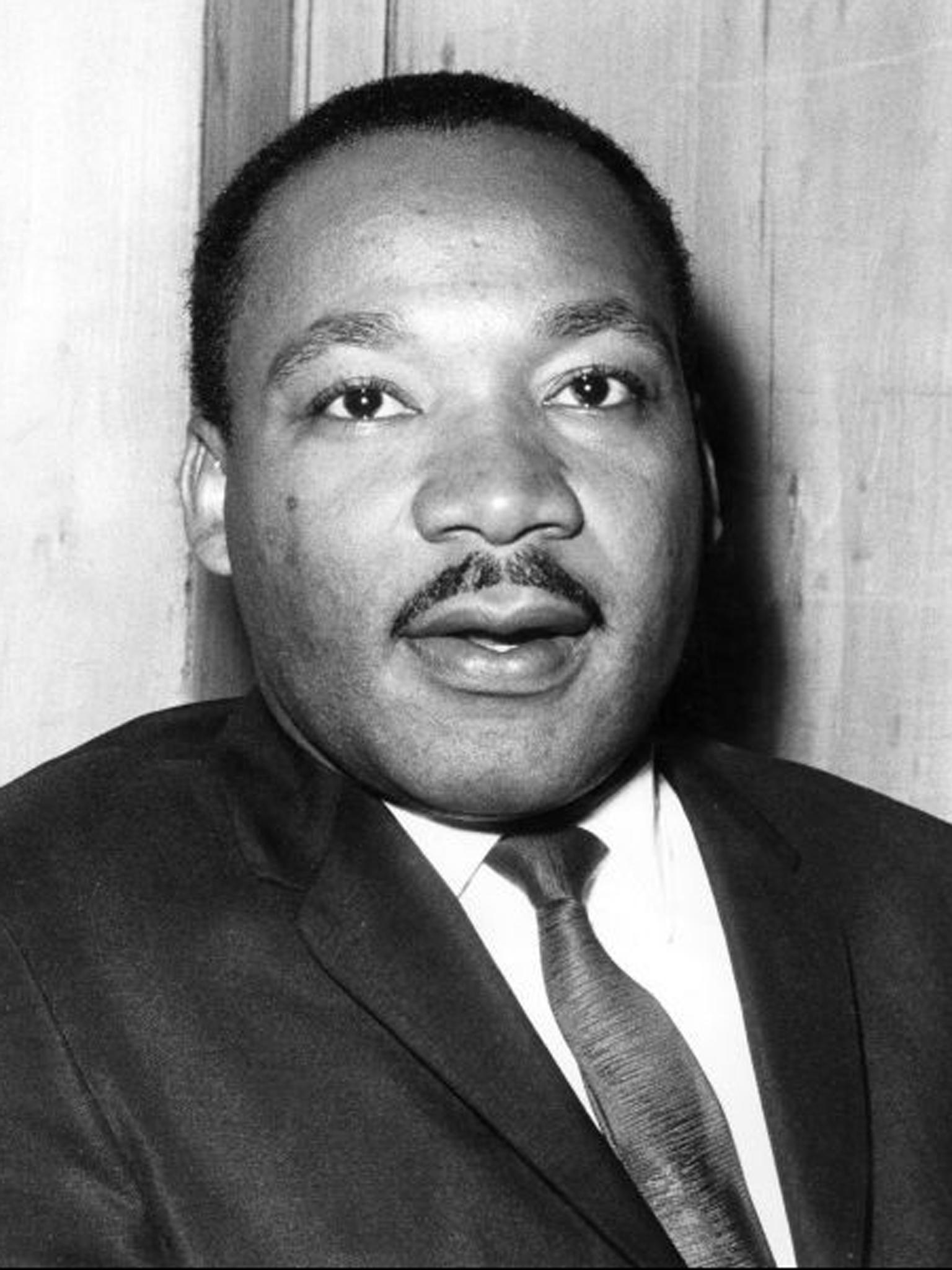

'The word "Wait!" rings in the ear of every Negro with piercing familiarity': 50 years on Martin Luther King's letter from Birmingham jail is still a remarkable work

In 1963 Dr Martin Luther King defended his campaign of direct action to religious leaders calling for negotiation. Here, in an edited fragment, is some idea of the power of King’s words and the clarity of his vision

Some 50 years ago this week one of the great documents of the twentieth century was written in a prison cell on scraps of newspaper pages smuggled out to a lawyer. Its author was Dr Martin Luther King, newly imprisoned for taking his campaign of non-violent protest to the streets of Birmingham, Alabama, then America's most cussedly bigoted and segregated city.

Little known outside the United States, or to civil rights specialists, the ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail’ is a remarkable work, justifying his actions, in the cadences and soaring language which King would make immortal a few months later in his ‘I Have A Dream’ speech at a Washington rally.

The letter was written in response to a plea, by eight white ministers of religion, for King and his comrades to stop their protests and settle instead for a policy of patient waiting and the hope of negotiation.

King’s letter is 7,000-words long. Here, in an edited fragment, is some idea of the power of King’s words and the clarity of his vision.

Time, and the progress swiftly made by him and his supporters, are a vindication of all that he worked and yearned for.

Letter From Birmingham Jail

16 April 1963

My dear fellow clergymen:

I am in Birmingham because injustice is here… I cannot sit idly by in Atlanta and not be concerned about what happens in Birmingham. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere…. There can be no gainsaying the fact that racial injustice engulfs this community. Birmingham is probably the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States. Its ugly record of brutality is widely known.

You may well ask: “Why direct action? Why sit-ins, marches and so forth? Isn't negotiation a better path?” You are quite right in calling, for negotiation… The purpose of our direct-action program is to create a situation so crisis-packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation. … Too long has our beloved Southland been bogged down in a tragic effort to live in monologue rather than dialogue… For years now I have heard the word “Wait!” It rings in the ear of every Negro with piercing familiarity. This “Wait” has almost always meant “Never.” We must come to see, with one of our distinguished jurists, that “justice too long delayed is justice denied.”

… We have waited for more than 340 years for our constitutional and God-given rights. The nations of Asia and Africa are moving with jet-like speed toward gaining political independence, but we stiff creep at horse-and-buggy pace toward gaining a cup of coffee at a lunch counter. Perhaps it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging dark of segregation to say, “Wait.” But when you have seen vicious mobs lynch your mothers and fathers at will and drown your sisters and brothers at whim; when you have seen hate-filled policemen curse, kick and even kill your black brothers and sisters; when you see the vast majority of your twenty million Negro brothers smothering in an airtight cage of poverty in the midst of an affluent society; when you suddenly find your tongue twisted and your speech stammering as you seek to explain to your six-year-old daughter why she can't go to the public amusement park that has just been advertised on television, and see tears welling up in her eyes when she is told that Funtown is closed to coloured children, and see ominous clouds of inferiority beginning to form in her little mental sky, and see her beginning to distort her personality by developing an unconscious bitterness toward white people; when you have to concoct an answer for a five-year-old son who is asking: “Daddy, why do white people treat coloured people so mean?”; when you take a cross-country drive and find it necessary to sleep night after night in the uncomfortable corners of your automobile because no motel will accept you; when you are humiliated day in and day out by nagging signs reading “white” and “coloured”; when your first name becomes “nigger,” your middle name becomes “boy” (however old you are) and your last name becomes “John,” and your wife and mother are never given the respected title “Mrs.”; when you are harried by day and haunted by night by the fact that you are a Negro, living constantly at tiptoe stance, never quite knowing what to expect next, and are plagued with inner fears and outer resentments; when you go forever fighting a degenerating sense of “nobodiness” then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait. There comes a time when the cup of endurance runs over, and men are no longer willing to be plunged into the abyss of despair. I hope, sirs, you can understand our legitimate and unavoidable impatience.

I have travelled the length and breadth of Alabama, Mississippi and all the other southern states. On sweltering summer days and crisp autumn mornings I have looked at the South's beautiful churches with their lofty spires pointing heavenward. I have beheld the impressive outlines of her massive religious-education buildings. Over and over I have found myself asking: “What kind of people worship here? Who is their God? Where were their voices when the lips of Governor Barnett dripped with words of interposition and nullification? Where were they when Governor Wallace gave a clarion call for defiance and hatred? Where were their voices of support when bruised and weary Negro men and women decided to rise from the dark dungeons of complacency to the bright hills of creative protest?”

I hope the church as a whole will meet the challenge of this decisive hour. But even if the church does not come to the aid of justice, I have no despair about the future… Abused and scorned though we may be, our destiny is tied up with America's destiny. Before the pilgrims landed at Plymouth, we were here. Before the pen of Jefferson etched the majestic words of the Declaration of Independence across the pages of history, we were here. For more than two centuries our forebears laboured in this country without wages; they made cotton king; they built the homes of their masters while suffering gross injustice and shameful humiliation-and yet out of a bottomless vitality they continued to thrive and develop. If the inexpressible cruelties of slavery could not stop us, the opposition we now face will surely fail. We will win our freedom because the sacred heritage of our nation and the eternal will of God are embodied in our echoing demands.

The full text of the letter can be read here

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies