A hero of Spanish cinemas: Meet the man who opened 14 small film houses in the remote regions of Catalonia

97-year-old Javier Escarceller fought to open a cinema during Spain’s great recession in 1951. He explains his obsession – and how he is determined to keep it open in equally troubled times

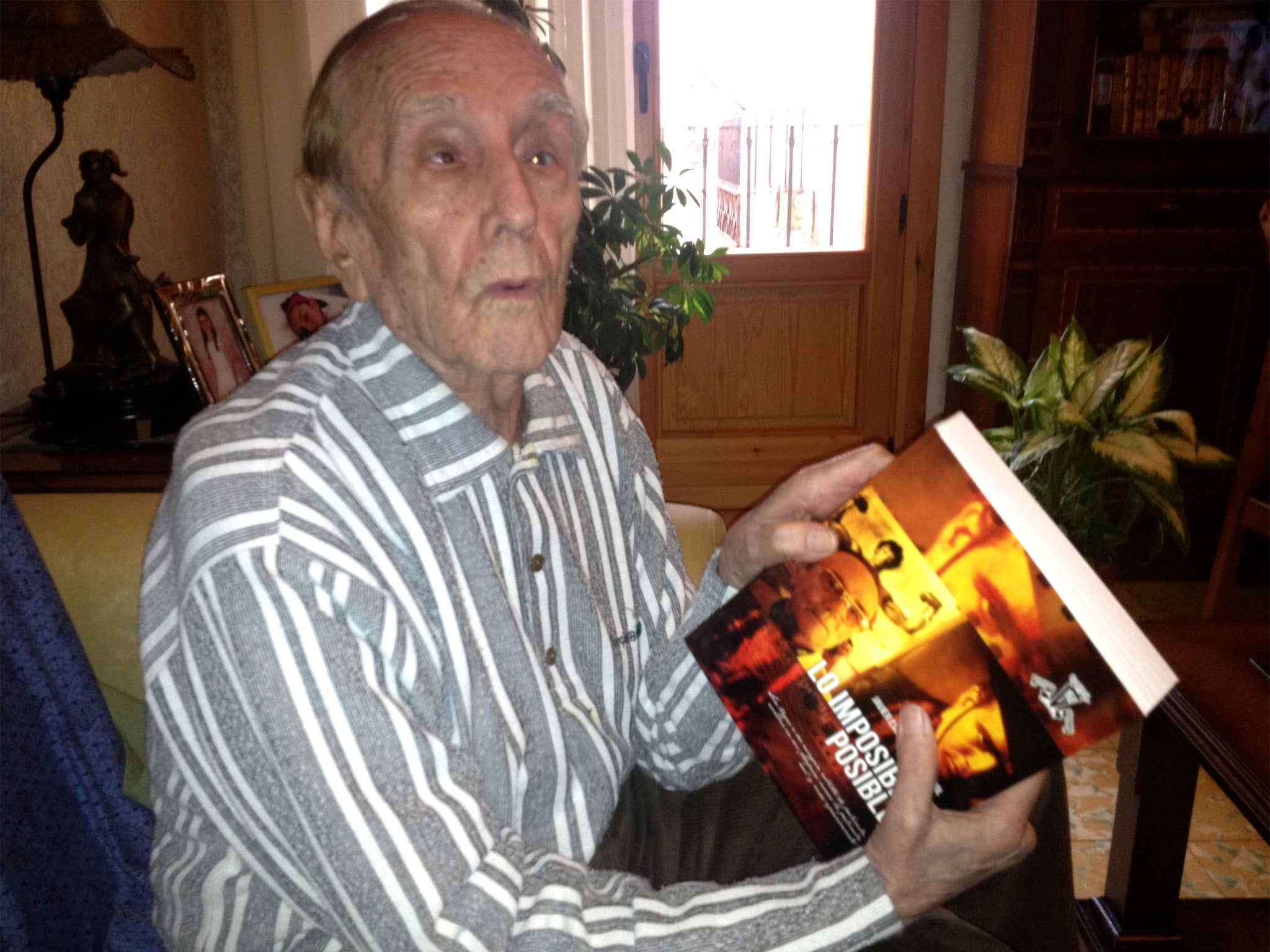

His autobiography is entitled Lo Imposible, Posible – “Making the Impossible Reality”– and in the case of 97-year-old Javier Escarceller, his dream, more than six decades ago, was to build a cinema in a tiny village in one of Catalonia’s most remote regions.

Not only did Mr Escarceller manage to do that, his cinema in the village of Caseres – population 300 and still accessible only after a lengthy drive through the dense woodland and high moors of South-west Catalonia – is still running: a success story that is even more remarkable given recession-blighted cinemas in towns and cities across Spain are currently closing in droves.

Sitting in his niece’s living room in Caseres, Mr Escarceller has just come back from a hospital appointment because of long-standing health problems, and he has some difficulty walking. However, his recollections of how, since 1951, he created and maintained Spain’s real-life version of the Italian cult movie Cinema Paradiso – where an impoverished Sicilian village battles to retain its cinema – show no sign of weakening.

Mr Escarceller was born in 1917 into a very poor family of farm workers and after fighting in the Civil War on both sides, including that conflict’s last great battle at the nearby River Ebro, he became mayor of Caseres at the age of 27. Yet despite the village being accessible only over unsurfaced country backroads, and Spain being in the throes of its worst ever modern-day recession – still known as 'the Years of Hunger' – he was still determined to go ahead with his project.

“The first thing to get was electricity for the village,” he tells The Independent, “and after a year as mayor, I managed to do that. But there was no money for the cinema itself.

“The local capitalists weren’t interested, they thought it was impossible. Fortunately, there were seven Civil Guards based here to fight the Maquis” – guerrilla fighters from Spain’s losing Republican side – “and they loaned me the money to buy the equipment.”

All of it was then shipped on the cart-tracks from the coast 60 miles away, while Mr Escarceller painstakingly gained, one by one, the 20 different licences needed to run a cinema under General Franco’s bureaucracy-obsessed local authorities.

And so the Cine Moderno, later renamed the Cine Vendrell, was born. An old warehouse in the middle of Caseres’s narrow streets was used for the projection of its first film on 31 August 1951, Agustina de Aragon, the stirring biopic of one of Spain’s cult heroines from the Napoleonic wars of independence.

“It was what everybody liked the most round here in those times, folk-lorey stuff, lots of Andalusian dancing, flamenco and so on,” he recalls. “They couldn’t identify so easily with films from outside Spain. I tried showing them The Great Caruso” – the 1951 smash biopic of the Italian opera star – “and they all walked out and went off to watch something Spanish-made in the next village instead.”

Each ticket cost four pesetas – about 5p – and for the first films villagers had to bring their own seats. “There were too many people to fit in the cinema, and I had to go outside and face off the rest of the mob of people trying to get in,” he recalls.

Mr Escarceller says his love of cinema came from seeing films in the nearest small town, Mora d’Ebre, about 40km (24 miles) away, as a teenager. “It was like something lit up in me and grew and grew,” he says. And the depth of his obsession becomes clear when he uses films to explain how determined he has been to keep the cinema open in Caseres.

“I had to have the same kind of tenacity shown by Rocky,” – the boxer in Sylvester Stallone’s films – “and the same ability to never to show any suffering as Marlon Brando in [the 1961 western] One-Eyed Jacks, to pretend everything was OK even when it wasn’t,” he says.

As a tribute to their inspiration, his two screen heroes feature on the cover of Lo Imposible, Posible, whose 600 pages are crammed with anecdotes from his career, complete with photographs of the cinema’s first tickets and the hand-held cardboard fans that for years served as “air-conditioning”.

Audiences were so big that Mr Escarceller managed to convert the warehouse into a 140-seat cinema, still being used today, although 14 years of continuous opposition from the local priest for showing films with overly racy content was perhaps the biggest threat to its existence. “They [the religious authorities] were like eagles digging their claws into me. They didn’t just want to shut the cinema, they wanted to kick me out of the village,” he recalls.

But they did not succeed, and Mr Escarceller has managed to open 14 cinemas in small villages in the same region, and he and his nephew deliver the film reels from one weekly showing to another. However, the cinema in Caseres remains the cornerstone of his business.

“We haven’t closed for a single week since 1951; whatever’s being premiered in Barcelona is shown here the same day,” he says proudly. “No other village in Spain as small as here has had such a high level of access to such culture.” It is perhaps no surprise that his favourite film is Cinema Paradiso: “There’s so much in there I can identify with,” he says.

However, the financial headaches facing the Spanish film industry also pursue Mr Escarceller. He claims thousands of cinemas have closed countrywide in the last decade and the total number of cinema tickets sold annually in Spain has plummeted from 141 million to 79 million in the past 10 years. Furthermore, the population decrease in much of Spain’s countryside continues apace in his region: picturesque as Caseres is, on a Saturday morning its streets are almost deserted, its one bar is closed and the mayor’s office is open “by appointment only” just two hours a week on Tuesdays.

Mr Escarceller admits times are difficult. “We only had four people in for last week’s showing,” he says, “and that won’t even pay for the electricity bill.” His next challenge, he says, will be converting the cinema’s projectors to digital. “We’re getting rid of the drums [of film reels] and all you’ll need is a tiny little packet, place it in a machine and it works. We’ll need a lot of money to do that, which we don’t have.”

However if anybody can keep the Caseres cinema going, it is surely Mr Escarceller. As he puts it “I made a vow that whilst I was alive, the cinema would not die. You need a level of commitment that businessmen with 1,000 times more money sometimes do not have, and to be a bit of a bohemian, too.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies