The Big Question: How serious is the political unrest on the Continent, and can it be calmed?

Why are we asking this now?

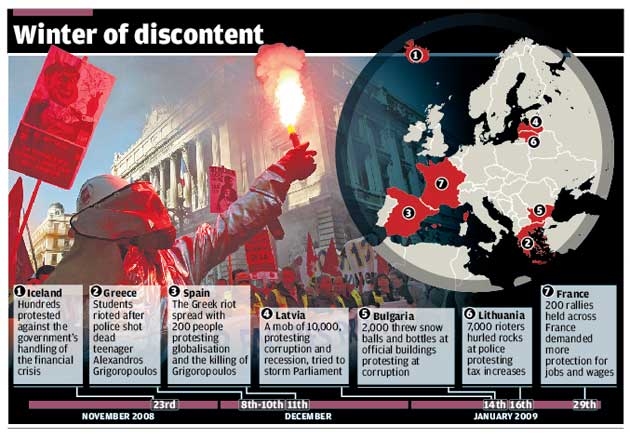

As the economic consequences of the credit crunch rumble across Europe, producing soaring unemployment rates and falling wages, protesters are taking to the streets in more and more countries to voice their anger.

Like where?

Yesterday saw the first mass demonstrations against the government response – or lack of it – to the economic crisis in France, where, in the biggest protests for many years, more than a million demonstrators turned out across the country, demanding that President Sarkozy do more to stanch the economic bloodletting. Public transport was drastically reduced, and one third of teachers stayed away from their schools. Factory, postal, hospital and many other workers struck. Even some staff at the Paris stock exchange joined the protests.

Why did the strike call produce such a response?

Unemployment in France is soaring at the fastest rate for 15 years, consumer spending has plummeted, and the eight unions which combined forces to stage the protest say the €26bn stimulus package that President Sarkozy announced recently is a woefully inadequate response to the crisis. Nearly 70 per cent of the French population was said be in favour of the protests.

Where did all this start?

The shooting dead of a teenager by a policeman in Athens in December unleashed weeks of violently destructive demonstrations, not only in the Greek capital but across the country. Although sparked by the killing, it became clear that what underlay the protests and made them so large and widespread was the country's galloping economic malaise.

Why was Greece affected first?

As the weakest member of the Eurozone economically, Greece is suffering disproportionately from the credit cruch and has none of the cushions of its wealthier fellow-members in northern Europe. Lacking competitive industry and agriculture, it has been heavily dependent on services, shipping and tourism – all of which have been sliding as consumers worldwide cut back on their spending. Last week Standard & Poor delivered another blow when it downgraded Greece's credit rating, arguing that the crisis had aggravated the Greek economy's "underlying loss of competitiveness."

How do these factors translate into problems for ordinary Greeks?

The protests were overwhelmingly by the young, and it is the young who have been most drastically affected, with youth unemployment rates of up to 30 per cent and many graduates forced to take menial jobs. But this week another disgruntled sector hoved into view as Greece's farmers blockaded the capital with more than 9,000 tractors to demand that the government hike its emergency support package to them of €500m.

Where else have protests broken out?

France aside, the countries affected have been small, historically weak ones which grew rapidly richer during the recent boom but are now being hit from every direction at once, with rising unemployment and wage and budget cuts, combined in the case of Latvia with tax increases mandated by the IMF. It's countries like Latvia and Lithuania that are the walking wounded of the credit crunch. Dominique Strauss-Kahn, head of the IMF, recently singled out Latvia, Hungary, Belarus and Ukraine as among the most vulnerable to turmoil.

What's the Latvian story?

During the boom its growth rates were in double figures, putting it among the champions of the EU, but last year the economy shrunk by 2 per cent and is forecast to sink by another 5 per cent in 2009, while unemployment has doubled in the past six months to 8 per cent, with three times that rate for young people.

So Latvians are angry?

Very. This is a country with little history of violent protest, but earlier this month a peaceful demonstration in the capital, Riga, by more than 10,000 people degenerated into a drunken riot in which 25 people were injured and 106 arrested. Public anger about the economy had been exacerbated in December when a leading member of the government, quizzed about the reasons for the economic crisis, told the TV interviewer, "Nothing special." The phrase infuriated many Latvians, and became an ironic slogan of the demonstrators.

What action were the protestors demanding?

Go home, and let other people take over. Government spokesmen argued in vain that the problem had its roots in reckless economic decisions made by the previous administration.

So the protests were pretty incoherent?

That's a feature of all the protests so far, and it reflects the confusion of governments at which the demonstrators are protesting. The authorities are flinging everything they can think of at the crisis, reversing years of economic wisdom and pulling every lever in sight in the hope that something might work. So far nothing has , despite the vaporisation of tens of billions of euros in the process. As panic grips Cabinet rooms across the Continent, the public is driven to fury.

But no government has fallen?

Wrong: Iceland's coalition government succumbed last week, after protests by 8,000 people were quelled by tear gas. A caretaker government is filling the breach, and elections will be held in a couple of months.

Where is all this going?

Nowhere good, is the broad consensus. Those who have long been sceptical about the validity of European Monetary Union are chortling with schadenfreude as the Eurozone's weaker members, sometimes offensively known as the Pigs – Portugal, Italy, Greece and Spain – struggle to make ends meet inside the (relatively) strengthening currency, with weakening competitiveness and ballooning deficits exposing what the sceptics see as the innate contradictions of yoking economies as different as Germany's and Greece's in a single currency.

What are they saying could happen?

Some predict that one or more of the "Pigs" could eventually be booted out of the Eurozone altogether. Even those who scorn such a scenario – pointing out that in the midst of its worst ever economic and political turmoil Iceland is actually applying to join the Euro – fear stronger economies could exact a fearsome price for continuing to entertain the weaker ones.

What sort of price?

Basically, imposing the obligation to cut their swollen deficits. For instance Jean-Claude Juncker, the prime minister of Luxembourg, has proposed that the Eurozone as a whole might take on the debts of the weaker members. In return the governments of those countries would have to submit to having their budgets drawn up in Brussels. Deep budget cuts in the depth of a severe recession in countries such as Italy, with a long history of violent street protest, could only be a recipe for further political unrest.

Will the disaffection and protest spread to more European countries?

Yes...

* Despite throwing huge sums around, no government has a clue how to stop the rot

* Online technology enables political indignation to spread across the continent like wildfire

* No longer able to devalue their way out of trouble, the weaker Eurozone economies are sitting ducks

No...

* The Eurozone will rise to the challenge and its weaker members will take their medicine calmly

* Despite spiralling problems, Germany and the UK have yet to see any serious mass protests

* The auguries of doom are inescapable, but this panic may pass sooner than we expect

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks