Turkey constitutional changes: what are they, how did they come about and how are they different?

The model proposed by Turkey lacks the safety mechanisms of checks and balances present in other countries like the United States, observers say

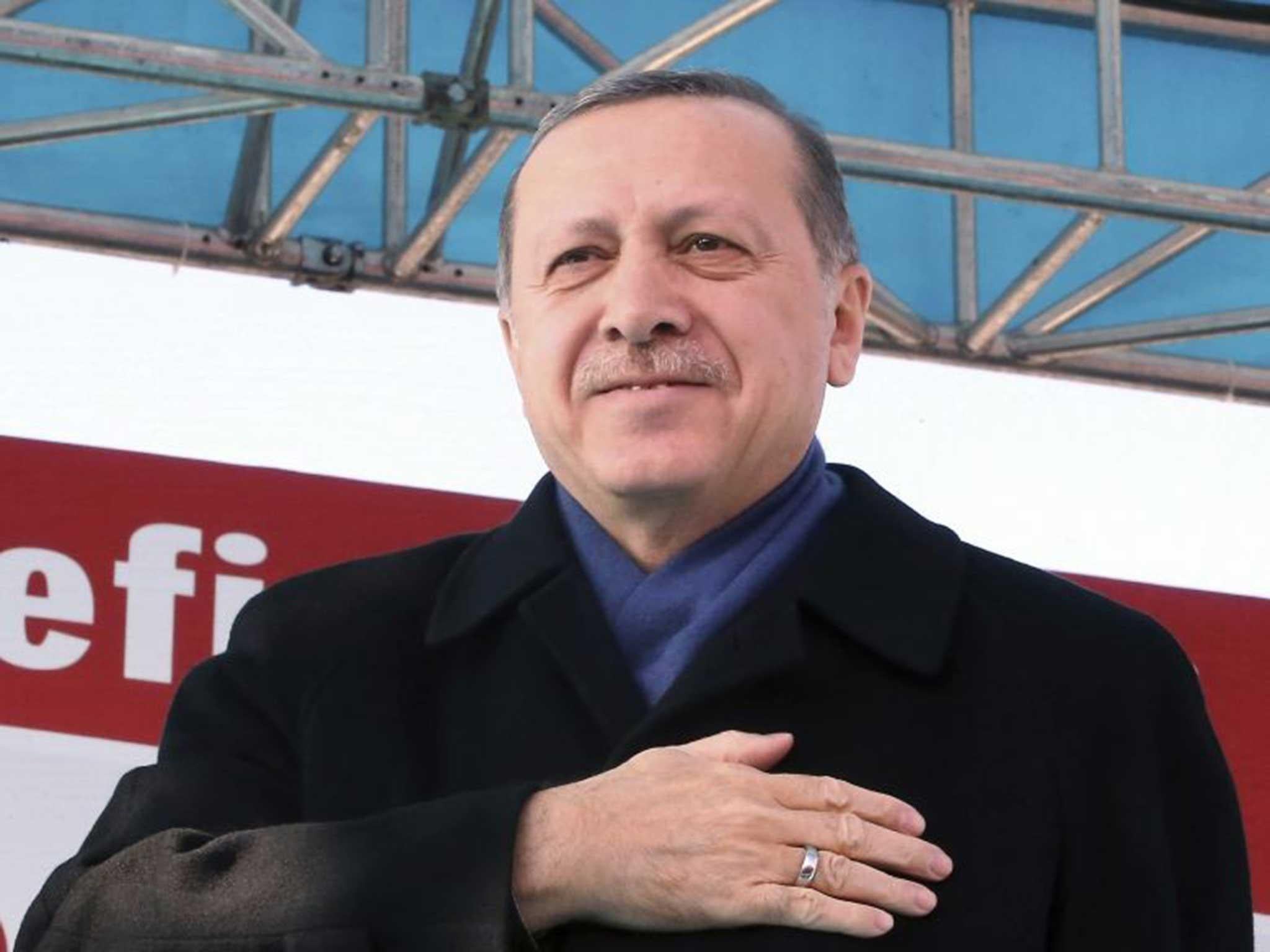

Turkey’s parliament has signed off on a contentious constitutional reform package that would concentrate even more powers in the office of the president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, and potentially extend his mandate till 2029. The reforms will come into effect if approved in a national referendum.

How it came about

Constitutional reform was first floated by the ruling party after it won the 2011 general election, but that failed to gain traction immediately.

In 2014, Recep Tayyip Erdogan became the country’s first directly-elected president and the idea of bolstering his office resurfaced.

The ruling Justice and Development Party, AKP, made the executive presidency central to its campaign promises in June 2015 general elections.

In November 2016, the nationalist party declared it would back moves to switch to a presidential system, saying Erdogan’s rule was a de-facto presidential system anyway.

The changes

The presidency would be catapulted from a largely ceremonial role to a nearly all-powerful position as head of government, head of state and head of the ruling party.

The office of the prime minister disappears, making way for a strong, executive president supported by vice-presidents. The president would have the power to appoint cabinet ministers without requiring a confidence vote from parliament, propose budgets and appoint more than half the members of the nation’s highest judicial body. The president would also have the power to dissolve the national assembly and impose states of emergency.

Parliament would be elected every five years, instead of every four, in general elections held in tandem with presidential elections.

The reform package also raises the number of lawmakers in parliament to 600 and lowers the age of political candidacy to 18.

Controversially, it also allows for a partisan president. To date, the symbolic head of state has been obliged to remain neutral and cut ties with his party.

It also introduces technical requirements that would make it harder for the assembly to remove the president from office or bring down his government with a vote of no confidence.

What makes Turkey’s proposed system different?

Turkey’s presidential system would allow Erdogan to be the head of state, the head of government and the head of the ruling party.

The model proposed by Turkey lacks the safety mechanisms of checks and balances present in other countries like the United States, observers say. The proposed changes transfer powers traditionally held by national assembly to the presidency rendering it a largely advisory body.

The context

The proposal comes six months after a violent coup attempt on 15 July 2016 failed to unseat Erdogan. The government reacted by declaring a state of emergency and sweeping purges that left no government institution untouched.

More than 100,000 civil servants have been dismissed for their alleged ties to the movement of Fethullah Gulen, a US-based cleric Ankara blames for the revolt. He denies involvement.

At the same time, Turkey is waging a multifaceted war against “terrorists,” a term encompassing Gulen supporters as well as the Islamic State group and Kurdish rebels at home, Syria and Iraq.

Turkey suffered dozens of stinging bombing attacks in 2016 in violence linked to the resumption of conflict with Kurdish rebels in the southeast and increased activity of foreign and local IS cells in Turkey.

The controversy

Supporters of a powerful presidency argue that a strong president would strengthen Turkey as it confronts a broad array of internal and external security threats.

Critics say that the reforms concentrate too many powers in the hands a leader who has increasingly displayed authoritarian tendencies. They point to anti-terrorism campaigns that have decimated an opposition pro-Kurdish party, the closure and government takeover of dozens of media outlets, the detention of more than 100 journalists, and hundreds of defamation lawsuits brought against individuals who “insulted” the president.

They also say that holding a referendum when the country is under a state of emergency prevents the opposition from campaigning freely against the proposed changes.

What next?

Turkish authorities say a referendum on the reforms will be held between late March and mid-April. If more than 50 per cent of voters approve it, the reforms would come into effect.

Parliamentary and presidential elections would be held at the same time in 2019.

The constitutional changes would also reset the clock on term limits, giving Erdogan the possibility of continuing as president until 2029.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks