Why we should be scared of Marine Le Pen's Front National

It has repackaged some of the most destructive and sweetly persuasive ideas of the hard right – xenophobia, protectionism, authoritarianism – into a seemingly modern programme for office

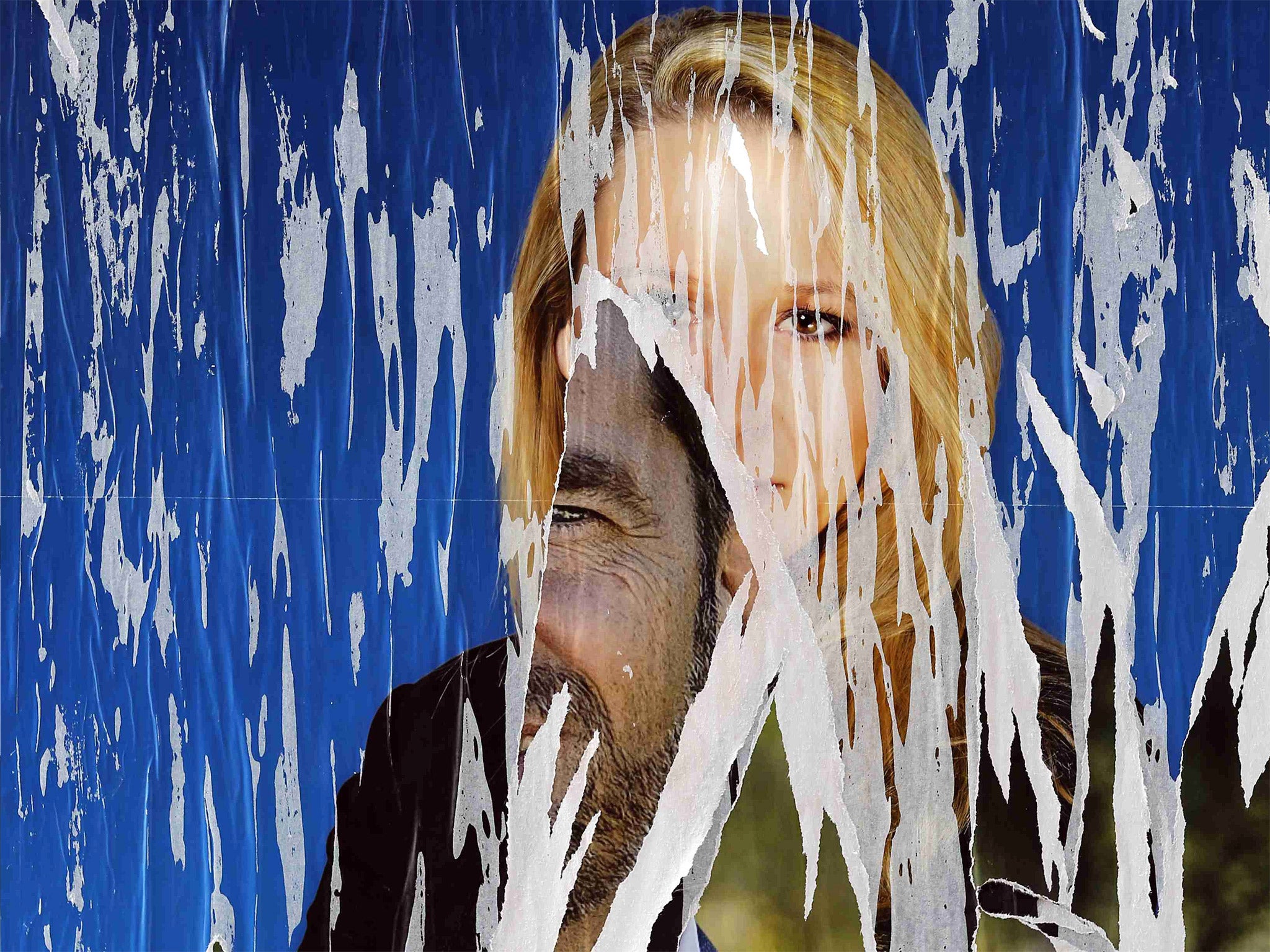

The most terrifying thing about Marine Le Pen is how likeable she is. She is relaxed, fluent, chatty and funny. You may detest what she stands for but it is difficult to resist her confident charm – rather like Nigel Farage in a blonde wig.

Ms Le Pen set alarm bells jangling all over Europe on Sunday with her party’s stunning performance in the first round of the French regional elections. If the results are confirmed this Sunday, from January the Front National could preside over three of the biggest regions in France with a combined population of 16,000,000 – the same as the Netherlands. Even if Ms Le Pen falls short – other parties were scrambling to try to block her yesterday – Sunday’s result establishes her deodorised far-right party as the biggest single force in French politics.

Should we be scared of the FN? Should we be scared of Ms Le Pen?

Yes.

We should be scared of Ms Le Pen because she has repackaged some of the most destructive and sweetly persuasive ideas of both the hard right and the hard left – xenophobia, protectionism, authoritarianism – into a single, seemingly modern programme for government.

We should be scared of Ms Le Pen because her updated politics of intolerance have invaded and hollowed out the traditional politics of the centre-right. One of most striking features of Sunday’s election result was the collapse of the vote of Nicolas Sarkozy’s supposedly moderate right, especially in southern France.

That the FN should take almost 28 per cent of the nationwide vote on Sunday was a calamity easily foretold. Ms Le Pen took 25 per cent of the vote, on a similarly low turnout, in local and European elections last year.

Since then, events might have been scripted by Ms Le Pen: the immigrant crisis this summer; the 13 November jihadist attacks on Paris; the failure of President François Hollande’s cautious but necessary market-opening reforms to reverse the rise in unemployment in France to a record level.

All the same, the “natural” party of opposition, Mr Sarkozy’s Les Républicains, should have triumphed on Sunday over an unpopular government. Instead, it was the NF which emerged as the main opposition force. This is disturbing – and has disturbing precedents.

Ms Le Pen’s father, Jean-Marie Le Pen, was obsessed with history and the lost far-right causes of the past (Vichy, French Algeria). It was his sincere allegiance to these old demons which caused their father-and-daughter of all quarrels earlier this year.

Ms Le Pen has deliberately erased the tape of that history. She says that she would have supported Charles de Gaulle against the Nazis and the collaborationist Vichy regime in 1940. She says that her “de-demonised” FN is not a “far-right” party but a patriotic champion of ordinary people, of all races and religions, against the betrayals of the “elites”.

Papa Le Pen comes from a French ultra-right tradition which existed long before Nazism and fascism; he is an anti-Semitic social conservative and an anti-government populist.

His daughter is both a “nationalist” (anti-European, anti-immigrant) and de facto a “socialist” (trade barriers and subsidies for industry; a higher minimum age; and a reduction of the retirement age to 60). She is also, as a double divorcee, socially liberal. She supports abortion and some gay rights. Many of the ambitious young men who surround her are openly homosexual.

On one level, this can be dismissed as a ragbag of policies and attitudes designed to appeal to every grievance and frustration in a country which has been spinning its wheels for four decades. Ms Le Pen has skilfully exploited the anger of a blue-collar and provincial middle-class electorate which berates politicians and demands “change” but refuses most specific changes. On the other hand, “nationalism” and “socialism” combined have a dark history, whatever Ms Le Pen may say. To that extent, the “Mariniste” FN is more authentically fascist – even if “fascist lite” – than her father’s party was.

In pictures: Extremists in the EU

Show all 6Exactly how “lite” is open to question. Several of the FN mayors elected in 2014, notably David Rachline in Fréjus and Robert Ménard in Beziers, have pursued a campaign of petty harassment and denigration of their local Muslim populations. Ms Le Pen’s niece, Marion Maréchal-Le Pen, said last week that it was not possible for French-born Muslims to be “truly French” because they did not share France’s Christian “traditions and values”.

Ms Maréchal-Le Pen, 25, a law student turned politician, is a rising force in the FN – not as likeable or clever as her aunt, nor as outwardly moderate. On Sunday, she may be elected president of the vast Provence-Alpes region, stretching from Marseilles to Nice.

Ms Le Pen herself has an even stronger chance of presiding over 6,000,000 people from the Pas-de-Calais to the outer Paris suburbs. If the FN can win in two such disparate regions – and also possibly Alsace-Lorraine-Champagne in the east – what is to prevent Ms Le Pen from becoming president in 2017?

Hervé Le Bras, a historian and expert on the far right, points out that Ms Le Pen’s 28 per cent is far short of the 50 per cent that she needs to win the second round of a presidential election. On the other hand, he says, Adolf Hitler only had “33 per cent of the votes” in Germany in the early 1930s before he “made alliances with some parties of the centre-right”.

One of the most intriguing implications of last Sunday’s result is that President Hollande, not Mr Sarkozy or any other centre-right candidate, might easily be Ms Le Pen’s opponent in the two-candidate presidential second round in May 2017. Would centre-right voters choose the failed reforming Socialist or the anti-European, national-socialist xenophobe? Polls suggest that it would be a miserably close-run thing, but that Mr Hollande would win. What, however, of the 2022 election, when Ms Le Pen will be just 54 years old?

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies