Isis in Iraq: Peshmergas have new weapon in fight against militants - the ability to read

An inability to understand signs can cost fighters their lives – night school aims to change that

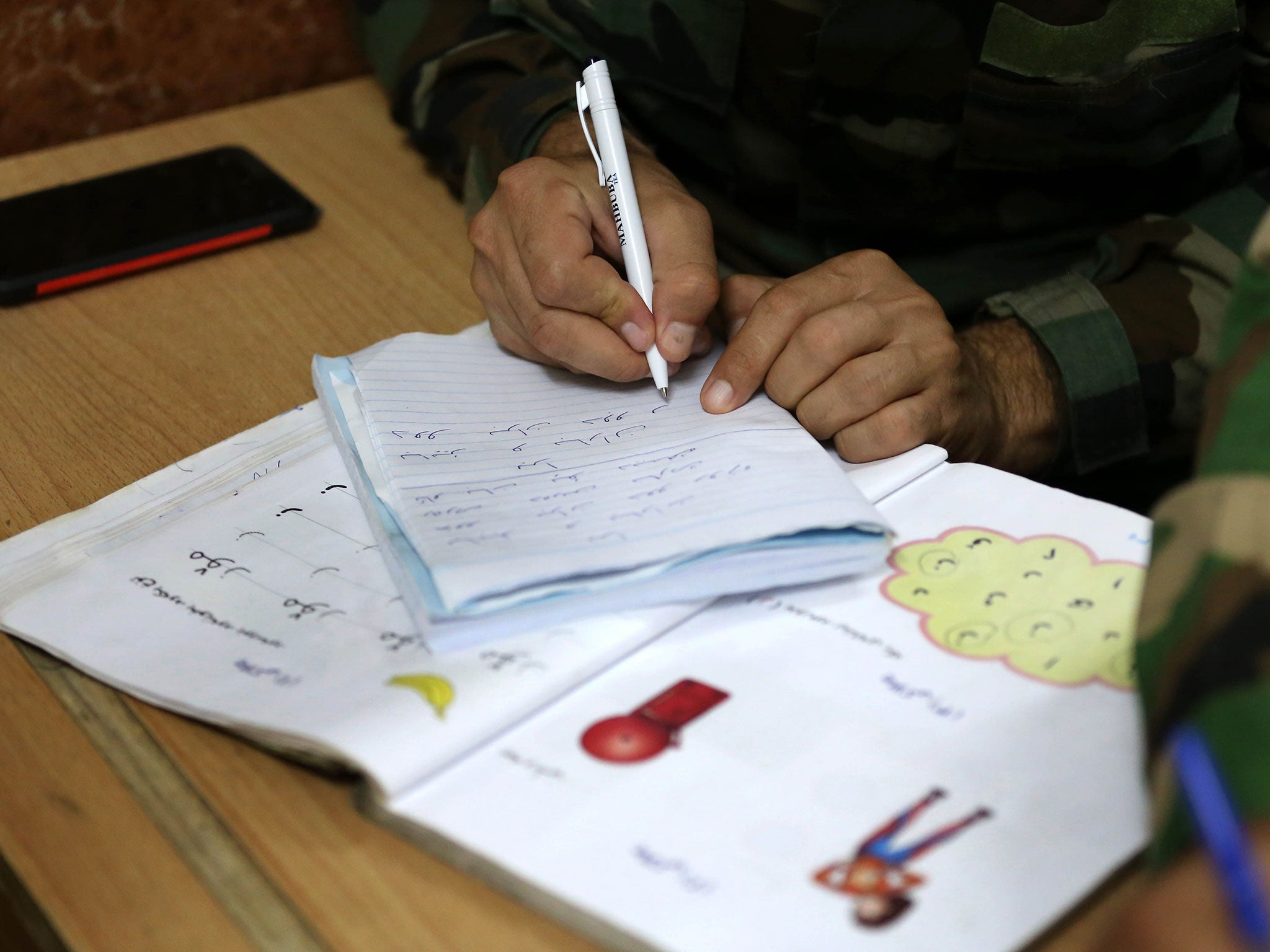

A student looks diligently up at his teacher and then down at an exercise book filled with rows of letters. Shkur Miro and the rest of the men listening carefully to what their teacher tells them are Peshmerga fighters, taking a break from the war with Isis.

In the past, fighters here had their schooling interrupted by conflict and poverty. Now they are taking night classes that could save their lives.

The location of the class is a closely guarded secret for the safety of the students.

Mr Miro, 33 is a fighter on the Makhmour front, 36 miles away from the region’s capital city of Irbil. “It’s really bothering me that I don’t know how to read road signs,” he says, after his evening Kurdish lesson. “When we go to the front line or into a recaptured village there are posters warning us not to touch things that are harmful and I can’t read them.”

Major Kamal Rashid, a representative from the Ministry of Peshmerga Affairs, said 10 Peshmerga soldiers have fallen into Isis hands because they could not read the road signs and went the wrong way. Since the start of the war around 1,300 Peshmerga have died and 7,000 have been wounded.

Major Kamal added that more education is needed so Peshmerga soldiers can benefit from the coalition’s training programme, which teaches the Peshmerga key battlefield skills. The idea behind the night school, said Major Kamal, is “to build an educated military force in Kurdistan”. The school fits around the schedules of the Peshmerga who work varied shifts but often spend 15 days on the frontline and 15 days off. They are paid around £345 per month so often must take other part-time jobs to survive.

Adding to the woes of the Peshmerga, who number more than 100,000, are salary delays stemming from a dispute between the regional government in Irbil and the government in Baghdad. Stalled public sector salaries are one of the factors plunging the region into discontent.

Many of the Peshmerga work under the control of Kurdistan’s ruling parties instead of the Ministry of Peshmerga Affairs, threatening further disunity for the region which experienced an internecine war in the 1990s, and is now suffering from a financial crisis, security threats and internal discontent.

Mr Miro is the oldest of six children and when he was growing up his father was a shepherd. “Because of financial problems I couldn’t even begin primary school,” he said. “My father wanted me to go but he was too old and had a problem with his eyes so I went to look after the sheep instead. I was taking care of all my siblings and I was like a father to them. I didn’t go to school for their sake, so they could study.”

Aside from the danger, Mr Miro has another reason to study: two children aged eight and six. “My wife says it is better for my kids if I am educated. At the moment my son is helping me with school work because he is in the second class in primary school and I am in the first,” he said.

Across the school’s courtyard, Mushir Fatih, 46, is leaving a geography class. He left school in the 1980s because of Saddam Hussein’s policies of oppression against the Kurds. “In school I was threatened. I could either join the Baath union or become a Peshmerga fighter in the mountains. I didn’t want to join the Iraqi army.” In 1991 he joined the Peshmerga. In 2013 he went back to school but his studying was once again interrupted by the war with Isis.

He is now fighting on a frontline north of Mosul, as well as studying geography, history and Arabic at secondary school level. In school he has learned about respecting human life, he said and “to not to be like Isis”.

Omar Aziz, 31 works in the Ministry of Peshmerga Affair’s arms depot and delivers weapons and ammunition along the 600-mile frontline. Financial difficulties meant he couldn’t finish high school.

My hobby now is to learn. Some people want to marry a second wife, but I say ‘I want to learn’, that’s my aim

But the night school is helping him in his job. “If we can understand new technology, such as GPS systems, that allows us to go straight to the frontline without any questions. We also need to be able to count ammunition and read the numbers and models of weaponry.”

Mr Aziz added that the teachers are helpful and take into account the difficulties faced by mature students.

Peshmerga schools are not a new phenomenon. During their guerrilla war against Iraqi government forces, fighters would study in the mountains in caves, sometimes pausing classes to hide from attack, said the principal of the school whose father ran a similar school in the mountains.

“There is nothing worthier than the Peshmerga except for God,” said Mr Miro, showing The Independent his exercise books filled with lines of carefully written letters. “My hobby now is to learn. Some people want to marry a second wife, but I say ‘I want to learn’, that’s my aim.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments