Isis steps up online propaganda war after defeat in Raqqa warning, 'We are in your home'

Jihadist posts picture of himself outside New York City's Metropolitan Museum of Art just before New Year's Eve on terrorist web channels as ominous reminder of threat group still pose

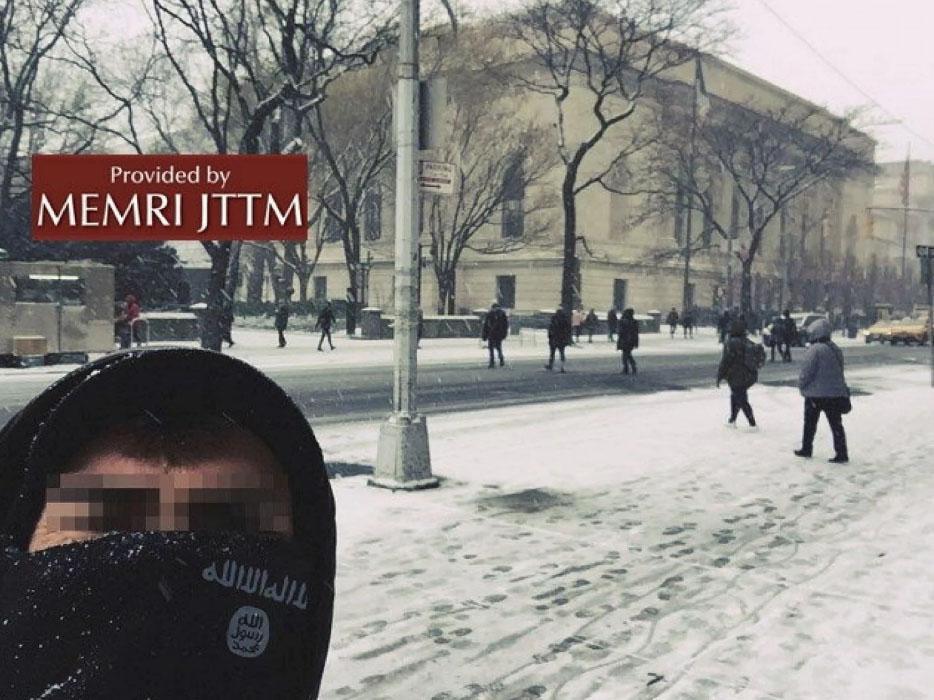

The man with the Isis scarf appears to be playing a kind of jihadist peekaboo.

In the photo, he hides his features behind the terrorist group's infamous logo but shows just enough background scenery so viewers can recognise his location: New York's Central Park, in wintertime.

“We are in your home,” reads the photo's simple caption, posted online a few days after Christmas and circulated widely on a prominent jihadist internet channel.

Precisely when the photo was taken is not known, but the message is chillingly clear. It has been repeated in similar posts in recent weeks, all purporting to show Isis operatives casing landmarks in Western cities and urging followers to carry out attacks wherever they are. “It is time to harvest the heads,” the narrator in one such video states.

Such is the typical fare served up by Isis's propaganda machine, which remains very much alive three months after the fall of the terrorist organisation's capital in Raqqa, Syria. The self-proclaimed caliphate has been reduced to a handful of villages in the Syrian desert, but the “virtual caliphate” fights on, a diminished but still formidable presence focused on rallying the group's followers in the face of crushing military defeats, according to US officials and independent analysts.

The content has changed significantly since the loss of Raqqa, formerly home to the group's official media division and production facilities. Gone are the glossy Isis magazines and slick videos extolling the virtues of life under militant Islamist rule. In their place is a steady stream of incitements, nearly all of them aimed at offering encouragement and detailed instructions for carrying out terrorist attacks.

Some are amateurish and appear to originate not from studios or official spokesmen, but from bloggers and other volunteers who often are only loosely affiliated with Isis - the online equivalent of lone-wolf terrorists who act without official guidance or instruction. Terrorism analysts say Isis is growing more dependent on such independent platforms, which are capable of distributing highly targeted appeals in scores of local languages and can't be easily silenced by military strikes.

At the same time, there are signs of new life from the group's official mouthpiece. Last week, Isis's Amaq News Agency issued its first English-language communiques since mid-September, just before the fall of Raqqa. The first weeks of 2018 have also seen a sharp rise in traffic on pro-Isis social media accounts compared with previous months, according to an analysis released Friday by the SITE Intelligence Group, a private firm that monitors jihadist content.

“The Islamic State is now showing the first signs of a regrouping media operation,” said SITE Executive Director Rita Katz. “The group suffered major setbacks by coalition and regime attacks but is now clearly taking major steps to reassemble its propaganda operation, which is among its most dangerous weapons.”

The newest propaganda campaign illustrates the difficulties faced by counter-terrorism officials in seeking to stop militants from connecting with would-be terrorists in the United States and throughout the West. Even after destroying the Isis's sanctuary and successfully blocking - with help from private companies - hundreds of the group's social media accounts, the terrorists and their supporters continue to find ways to get their messages out, analysts say.

“The depletion of Isis on the battlefield has not yet translated into the degradation of Isis in the online space,” said Tara Maller, a former CIA military analyst and senior policy adviser for the Counter Extremism Project, a nonpartisan group that promotes policies to block extremist content online. “What we see is a continuing effort to engage online and an increased effort to inspire people to carry out lone-wolf attacks.”

US officials and analysts have been watching closely to see how the collapse of the caliphate would affect the group's propaganda machine, the driving force behind Isis's rise to global prominence. Beginning in Syria in 2013, the group's leaders spent millions of dollars creating a nimble, technically savvy media operation with a heavy social media presence.

Under Presidents Barack Obama and Trump, the Pentagon and CIA tried different measures to knock the terrorists offline. US fighter jets and drones bombed Isis's production houses and stalked its spokesmen, while the State Department pressed YouTube and other social media companies to block the militants' Web channels and chat rooms. In response, the terrorists shifted tactics, migrating to different social media platforms and cultivating a global network of allies to amplify official messages and post their own pro-Isis content.

Still, the fall of Raqqa in October resulted in a steep decline in Isis's official media output. Rumiyah, the group's flagship online publication, appears to have ceased production entirely, while the number of routine posts and videos is down sharply. The analysis by SITE shows that Isis-affiliated websites put out a total of 907 communiques, reports and videos between November and December of 2016. During the same period this past year, the group and its supporters managed only 211.

An analysis published on 7 January by the national security blog Lawfare cites an overall drop in content of about 90 percent from Isis's high-water mark in 2015.

“This is not just a media decline - it is a full-fledged collapse,” the report's authors, counterterrorism researchers Charlie Winter and Jade Parker, write in the blog.

But volunteers have stepped up to fill the gap, analysts say. The broader web of militant commentators and videographers - a network that was encouraged and facilitated by Isis in its heyday - was designed to continue functioning even if the mother branch was completely shut down.

While many of the individual cyberwarriors have been around for years, Isis has become more reliant on them in issuing appeals for what Winter and Parker call “retributive terrorism” - acts of violence intended to avenge the group's losses while convincing followers and foes that it remains relevant.

“Before its territorial decline, a successful terrorist operation was a tactical bonus. Now, it is a strategic necessity,” the writers state. “The online sphere has been tailored to facilitate these attacks more efficiently than ever before.

The posting of the “peekaboo” jihadist's selfie in New York was part of a remarkable incitement campaign that began in the weeks before Christmas and continued through early January. Several videos and photographs that appeared online during the period sought to convey the impression that Isis warriors were lurking everywhere. The images depict well-known landmarks such as Paris's Eiffel Tower, the Sydney Harbour Bridge in Australia and the Los Angeles skyline.

The New York photo appears to have been taken outside New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art, on the edge of Central Park on the city's Upper East Side. It is unclear whether the photo is genuine or altered, but it depicts weather similar to that experienced by New Yorkers late last month, with pedestrians in heavy coats and hats trudging along sidewalks lightly covered with snow.

A commentary accompanying one of the videos warns of coming terrorist attacks while offering tips to supporters on how to unleash mayhem during the Christmas holiday season, when urban streets would be packed with shoppers and revellers.

“Make [explosive] devices and plant them in their celebrations,” it says, “or set their homes and forests on fire, or run over the largest number of unbelievers with your vehicle, or stab them repeatedly with a knife.”

Other postings in recent weeks offered detailed technical advice. On the messaging application Telegram, Isis supporters published a Knights of the Lone Jihad series with how-to manuals on everything from bomb-making to the poisoning of food supplies.

Experts who closely monitor jihadist channels say the overall impression is that of a vibrant propaganda machine that hasn't slowed appreciably or moderated its content. To ensure the broadest audience, the messages are typically translated into multiple languages, including English, Arabic, Russian, Urdu and even Chinese.

“When you look at the unofficial Isis material out there - the stuff posted by Isis supporters - that has not diminished,” said Steven Stalinsky, executive director of the Middle East Media Research Institute, a Washington nonprofit. “There is so much content - so many accounts, so many new chats - and more popping up every day.”

For whatever reason, the holiday season appeals did not bear fruit, although there was at least one close call. In mid-December, federal officials arrested a 26-year-old California man for allegedly plotting a Christmas-week attack on San Francisco's famed Pier 39 commercial area. US officials said the suspect, a former Marine, had expressed support for Isis on social media.

Both suspects in the two attacks in New York last year - Sayfullo Saipov, the Uzbek immigrant who ran over pedestrians with a truck in Lower Manhattan on 31 October, and Akayed Ullah, a Bangladeshi immigrant who exploded a crude bomb in a Times Square subway tunnel on 11 December - also told authorities they were inspired by Isis videos.

Each terrorism attempt - successful or not - serves as a reinforcer, generating waves of excitement among online jihadists while encouraging further use of the same tactics, said Stalinsky, who also is the author of American Traitor, a biography of the al-Qaeda propagandist Adam Gadahn.

“Even if it's a small attack, it pumps blood into the cyber-body of ISIS,” he said. “All it takes is one attack to produce a lot of energy for the online movement.”

The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks