Grapes of wrath: how wine could bottle the Israeli-Palestinian peace process

The labelling of Israeli settlement wine brings the battle over land in the West Bank to Europe, writes Bel Trew

Just a half an hour drive north of Jerusalem, atop a rocked-rippled hill in the West Bank, a battle with the European Court of Justice is under way.

Lush vines line the forehead of Jabel al-Taweel, or “tall mountain”, overlooking the Palestinian towns of al-Bireh and Ramallah. At its tip is a clutch of red-roofed houses surrounded by lands fat with fig trees and grapes that come to an abrupt halt with a snarl of barbed wire.

This is Psagot, an Israeli settlement, which like all Israeli settlements in the occupied West Bank, is illegal under international law (a point Israel disputes).

Since the mid-1990s it has also been home to a winery that now produces highly rated Israeli wine from vineyards built on stolen private Palestinian land.

The serenity of the area belies the international legal fight here, which is centred around wine bottle labels and has travelled from the Conseil d’État in Paris to the supreme court of the European Union (EU) in Luxembourg

The fight came to a head on Thursday and, according to both Palestinians and Israeli observers, is part of a bigger story of the steady collapse of a two-state solution to the decades-old Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Yaakov Berg, the wealthy Israeli owner of the Psagot winery, wants to cancel a 2015-imposed EU regulation that requires member states to specifically label products as coming from Israeli settlements in the West Bank, rather than Israel proper.

Mr Berg, who moved here from Russia when he was three years old, likens the labels to the yellow patches Jewish people were made to wear by the Nazis.

He argues that it is discriminatory against Israel, politicised and designed to encourage a boycott of his produce, and so a boycott of his country, although neither the EU nor the United Nations recognise Israeli settlements within the West Bank as being part of Israel.

Together with the US-based Lawfare Project, he first raised the case in Paris, where it was referred to Europe’s top court. On Thursday the court’s Advocate-General issued his opinion ahead of a final ruling.

“When you say ‘West Bank: Israeli settlement’ it’s a political definition it has nothing to do with geography,” he tells The Independent from a glass-walled room in his winery that overlooks hundreds of oak wine barrels.

He cited biblical texts as a reason why.

“In all the maps of the world, for 3,000 years it has been written that here [the West Bank] is Israel, everyone knows where Israel is.”

The winery could face financial troubles if the labelling impacts purchasing habits of people who may not want to buy from settlements.

Israel’s economy ministry estimated at the time the new regulation was introduced, it would cost producers around $50m (£40m) a year, affecting fresh goods such as grapes and dates, wine, poultry, honey, olive oil and cosmetics.

That is around a fifth of the $200-$300m worth of goods produced in settlements each year: a tiny drop of the $30bn of goods and services Israel exports to the EU annually.

For Mr Berg, 70 per cent of the 400,000 bottles his winery produces every year are exported, and Europe is one of his largest markets.

“The labelling is worse than wearing the yellow star [in Nazi Germany] which just says, ‘this is a Jew,” Mr Berg continues. “It is like a cigarette warning, [saying] it is dangerous to your health.”

Despite the pressure, on Thursday Advocate-General Gerard Hogan did not mince his words. He recommended that the EU keep the regulation, saying the settlements are a “manifest breach of international law”.

A violation of that, he continued, constitutes “the kind of ethical consideration which the EU legislature acknowledged as legitimate in the context of requiring country of origin information”.

In short, the labels should stay, he concluded.

Though unlikely, the court could choose to ignore this opinion and cancel the labelling requirements in a ruling due this autumn.

If it did this, it would mean the EU greenlights the right of Israel to loot land in the West Bank, warns Dror Etkes, an Israeli researcher who has spent two decades monitoring the Israeli settlement enterprise and heads up watchdog Kerem Navot.

The battle of wine bottle labels and even Psagot winery itself, he says, tells a larger story of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict at a time when many fear further encroachment on Palestinian territory.

In just two weeks, Washington is expected to unfurl Donald Trump’s long-awaited peace plan for the region, that already been rejected by the Palestinian leadership on the grounds it will likely be too pro-Israel.

The Palestinians cut diplomatic ties with the States when the US president recognised the disputed city of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital last year.

In March Mr Trump recognised the Israeli annexation of the Golan Heights, which it seized from Syria in 1967, sparking concerns he may do the same for areas within the West Bank.

A few days ago, David Friedman, the Trump-appointed ambassador to Israel, said in an interview he believed that Israel had the right to annex “portions” of the West Bank, worrying Palestinians further.

Like other Trump officials, Mr Friedman has implied that there should be continued Israeli military presence in the West Bank.

We are scared of annexation. No single person is not afraid

Palestinians see this as confirmation that the US has no interest in supporting the creation of a sovereign Palestinian state but would rather advocate officially handing over more land.

Amit Gilutz of Israeli rights group B’Tselem says that Israel already uses the vast majority of the resources in the West Bank – often fertile land needed for the development of a viable Palestinian economy – for its own use, at the direct expense of the Palestinians.

This week the rights group released a new interactive project, “Conquer and Divide”, illustrating Israel’s encroachment on Palestinian space “shattering land into small, isolated units, and keeping Palestinians apart from one another and from Israelis”.

Mr Etkes says one of the “main patterns” of this trend over the last 15 years was agricultural land grabs by settlers and the state, like Psagot.

Since 2004, nearly 1000 hectares of privately owned Palestinian land has been seized by the settlers for agricultural purposes, according to Mr Etkes’s own calculations based off decades of research and freedom of information requests from the authorities.

Of that nearly a quarter, just over 220 hectares, have been converted into vineyards like Psagot.

“This is especially happening in hill country… where religious hardcore radical settlements like Psagot are located,” he tells The Independent.

“It’s an attempt to take more land and to create sources of livelihood for settlers. Psagot is one of a few dozen settlements which specialise in private land grab for use of mainly vineyards,” he adds.

Back in the countryside surrounding the vineyard, the Palestinians who own that land, say every grab is a double loss.

“They are not only stealing our land but because we are forbidden to use it, it makes us less capable of providing for ourselves,” says Ka’anat Quran, 52, who owns the plot of land Mr Berg’s family home and first vineyard now sits on.

“We used to live off the products of the land – growing olives, figs, cereals, lentils. Now we are forced to purchase from outside,” she adds.

She says it dimmed hopes of Palestinian statehood:“Of course we are scared of annexation. No single person is not afraid.”

To Ka’anat and her cousin Karima, 50, who jointly inherited the 2.5 hectares on Jabal al-Taweel from their grandfather, the Psagot vineyards are known better to them as five-digit registry numbers.

They say they started to lose access to their fields in the area in the late 1990s as the settlers violently expanded their vineyards. They were finally sealed out when the Israeli military built a security fence enclosing the land in 2003 in the middle of the Second Intifada.

Although Mr Berg denies this to The Independent, Psagot’s first batch of vines, his own house and swimming pool appears to lie on a quarter of a hectare of Quran land, known as Parcel 233, block 17.

The Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT), the Israeli security unit which oversees civilian issues between Israel and the Palestinians, declined to comment about this on the record.

However, Israeli officials confirmed to The Independent the vineyards were located on private Palestinian land. The Palestinians owners and the Bireh municipal council showed documentation to The Independent that showed the Berg house lay specifically on Parcel 233, block 17 owned by the Qurans.

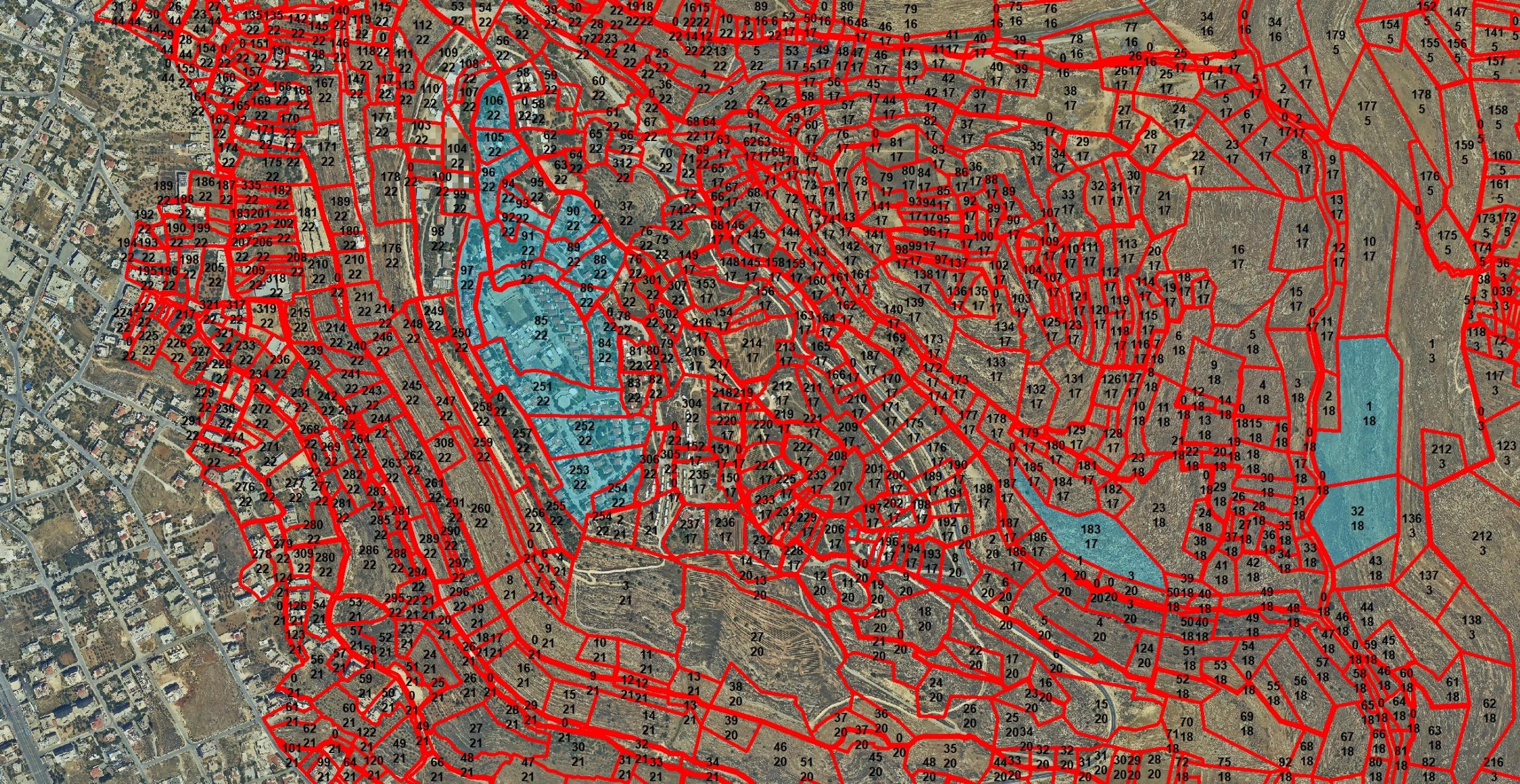

It is also verified by COGAT’s own log obtained by Mr Etkes, which shows a mesmerising grid of Palestinian land parcels, registered by the Jordanians, which lie under the steadily expanding plots of Psagot’s grape fields.

In fact in 2003 the Israelis themselves issued a demolition order against Mr Berg’s home (order number 252/03) as, even under Israeli law, his decision to build on the Quran’s privately own land is illegal. The order has yet to be enforced.

There have been efforts by the Palestinians to fight the land grab in the Israeli courts.

Munif Triesh, 69, a member of Bireh council who owns a plot adjacent to the Quran land, twice tried to have the settler caravans on his land removed. But although he claims the court initially admitted they were wrongfully erected, the case was finally dropped due to a technicality in 1998.

For the families, who live in the shadow of the settlement and its accompanying military outpost, the fight over labels on bottles thousands of mile way in Europe is not the most pressing issue. But they do fear the vineyards and the fine wines they produce are “wine-washing” their daily reality.

“After the evening sunset we are afraid to go out of our houses because of the threat of the settlers, we hear gunfire nearly every night from the soldiers,” Ka’anat claims.

“Every night we put ourselves in a kind of self-imposed prison because we are scared to leave our homes.”

Mr Berg denies that any violence is shown to the local inhabitants and maintains that in creating Psagot winery he has only “returned to his homeland not stolen land”.

“I think annexation is the reality already,” he says, adding that the Palestinians should thank the Israelis “10 times”.

“We came back to our homeland. Instead of desert we made it successful. The first guys that benefit are the Palestinians from our success. The place used to be desert, now it is green and working for everybody.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks