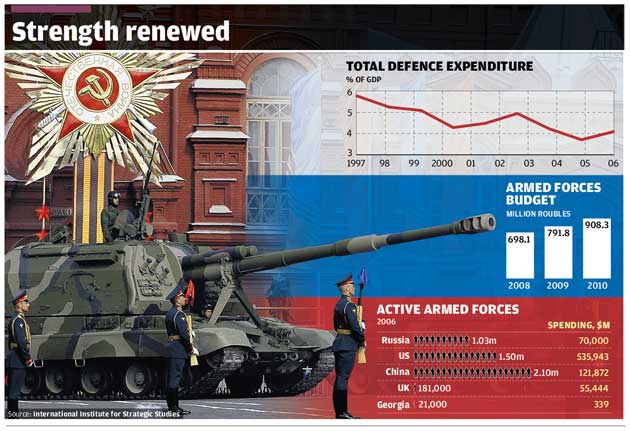

The Big Question: Why is Russia building up its armed forces, and should the West worry?

Why are we asking this now?

Russia's President, Dmitry Medvedev, addressed a combined meeting of the country's senior officers and top brass earlier this week, where he set out sweeping plans to modernise and upgrade the armed forces. It was the first time he had spoken at such a gathering in his capacity as President, and the occasion was widely seen as as underlining his status as commander-in-chief, a year after his election.

Did Medvedev warn that Russia was re-arming?

Yes and no. Outside Russia, many reports implied he had given the West notice of a new arms race in stressing Russia's intention to enhance its nuclear capability. He did say a long-range nuclear missile capacity would remain key to Russia's defence. But his central theme was not re-armament – nuclear or conventional – but the urgent need for Russia to modernise its armed forces in every respect: from structures and equipment to servicemen's pay and conditions.

So he was soft on the West?

Not exactly. He had a sideswipe against Nato, which – as he put it – "has not curbed its efforts to station some of its military infrastructure close to our borders". But you would expect this sort of thing from a national leader speaking to a military audience. It would have been strange if he had not at least alluded to US plans to station anti-missile installations in former Warsaw Pact countries that now belong to Nato. But he was careful not to name the US or any other country. He left the sabre-rattling to his chief of general staff, Anatoly Serdyukov, who accused the US of trying to secure its supplies of raw materials (ie. oil and gas) by stationing troops in Central Asia and elsewhere.

Does Russia need military reform?

And how. Aside from a new flag and new uniforms, almost everything about the Russian armed forces has remained unchanged since Soviet days. It is still almost entirely a conscript army. It retains a ponderous, top-heavy command structure (with one officer for every two-and-a-half men). Pay is abysmally low; housing for the rank-and-file is barely civilised, and much hardware is more than 20 years old. The collapse of the Soviet Union drastically reduced the prestige of the armed forces, whose retreat – first from eastern and central Europe, then from the Baltic States, and then from most other former Soviet republics in Central Asia and the Central Caucasus – was seen by many in Russia as a defeat. Germany helped, by paying for new housing to resettle many of the troops returning to Russia from East Germany, but that still left a huge shortfall. Then there were the two Chechen wars, in which Russian forces hardly covered themselves with glory.

What other problems need to be tackled?

Two especially intractable problems. The first is corruption. The armed forces, especially the less prestigious units, were beset by corruption even in the late Soviet period. But it escalated through the 1990s, as troops hawked everything they could, not just uniforms and firearms, but tanks and other hardware. Sometime this was for self-enrichment, and sometimes simply to survive. The second is bullying. Again, the problem goes back a long way. The campaign group, Soldiers' Mothers, came to prominence in the 1980s, and lobbied against brutal induction practices. Even now, more than 1,000 soldiers a year die from a variety of non-military causes, which include accidents and bullying.

Why has so little been done so far?

Partly because the logistical problems presented by so many returning troops were so great. Partly because there were more urgent priorities, such as the need to secure dilapidated nuclear installations – for which Nato supplied finance and expertise. And partly because Russia had a whole new border to defend after the Soviet Union collapsed and most of its military installations were in the wrong places. Russia's most heavily, and expensively, fortified border in 1992, for instance, was with Norway – because this was the single frontier it still had with Nato – but its greatest post-Soviet vulnerability was its southern flank. Of course, there was also resistance to reform among members of the top brass, across all services, who feared the threat to their status and expertise. The loss of the Kursk submarine in August 2000 showed Russia's military at its most closed and recalcitrant.

What makes reform so urgent now?

The Russian military and Russian politicians would offer a whole series of reasons. But there is really only one that explains both the timing and the sense of urgency: the experience of the brief war with Georgia last August. While Russia "won", to the extent that it was able to secure Georgia's two pro-Russian enclaves (South Ossetia and Abkhazia), the campaign exposed embarrassing weaknesses in Russia's capability. A bit like Britain having to reorient its Army away from notional tank battles for control of central Europe and towards desert and guerrilla warfare in Afghanistan and Iraq, Russia found itself having to fight Georgia's upgraded, Nato-compatible forces with Cold War-era structures and equipment.

What did Russia learn from the Georgia war?

Principally, how inflexible and backward its own forces were. Russia lost 66 servicemen, including the deputy commander in the field, and four warplanes. But officers are also said to have been shocked by Georgia's high-tech capability, including night-sight, which left Russian forces highly vulnerable in the dark. Ordinary conscripts were seized with envy at the standard of accommodation enjoyed by Georgian troops – and in at least one instance proceeded to trash it in their fury. The whole experience left Russia's high command shocked and – for the first time since the Soviet collapse – amenable to change.

Has there been no reform at all since 1992?

Not much. Both Boris Yeltsin in the 1990s and Vladimir Putin between 2000 and 2008 said they wanted Russia to have completely professional armed forces. But plans were always shelved, primarily for cost reasons, but maybe also because of the risk of higher youth unemployment. Putin did manage to bring the conscription period down from two years to one for the army; he also introduced a stipulation that only volunteers would serve in Chechnya. Pay was raised, but it is still very low, and a programme begun to improve military housing. But, as Mr Medvedev made clear this week, progress has been slow.

Should the West be concerned?

By any standards, the Russian military is overdue for reform. And while more efficient armed forces could present a greater threat, the opposite can also be argued. Reform should make the Russian military not only leaner, fitter and better equipped, but also more disciplined and more responsible. This should reduce the threat of unsecured nuclear materials and unruly troops. In the end, it will not be Russia's military capability, but its political stance that determines whether it constitutes a threat to the West.

Will President Medvedev succeed in modernising the Russian military?

Yes...

* He is determined. One of his first acts as President was to sack the Chief of General Staff.

* The experience of the war against Georgia proved that modernising the military could not be delayed.

* If Russia wants to increase, or even retain, its international influence, it needs a modern fighting force.

No...

* Modernising an outdated force of more than 1 million men will take at least a generation.

* The fall in oil and gas prices means that Russia will not be able to afford such a costly project all at once.

* The military is one of Russia's last unreformed institutions and there are those who want to keep it that way.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks