A History of the First World War in 100 Moments: Britain’s ‘enemy aliens’ get their own railway

Tens of thousands of Germans living in the UK were interned during the war. Simon Usborne finds out where they went

On the west coast of the Isle of Man, a narrow road leads from the tiny village of Patrick to a remote farm. It is unusually straight but otherwise unremarkable. Look closely at the low walls alongside it, however, and clues about the area’s past emerge. They are made of chunks of 100-year-old concrete. The rubble, which looks like stone, once formed the foundations of a giant, secure camp that at its peak housed more than 25,000 men. They were officially known as “enemy aliens”.

At the outbreak of war, Germans living in Britain – aristocrats, waiters and bakers among them – found themselves in sudden peril. Many had settled years before. But as Germanophobia consumed the country, men aged 17 to 55 were considered to be potential spies. Deporting them risked boosting the enemy ranks, so it was decided they should be locked up, inside Britain, for the duration of the war. Tens of thousands of men were registered. But where to keep them?

Alexandra Palace in north London became a holding camp for up to 3,000 “aliens”. They slept in rows on plank beds as their families survived outside, in increasingly hostile communities and with drastically reduced incomes. Other camps opened across Britain, swelling significantly in the anti-German backlash that followed the sinking of the Lusitania cruise liner in May 1915. By then the government had identified the Isle of Man as the perfect site for a larger, more secluded facility.

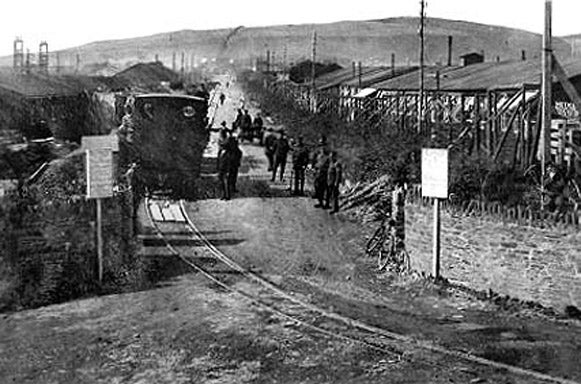

Knockaloe was by far the biggest internment camp in the British Isles. A village of 100 people became a complex of wooden sheds, housing 25,000 internees, significantly boosting the island’s existing population of about 40,000. By September 1915, the camp had grown so large that a railway line was opened along what is now the road out of Patrick. An engine shed is the only surviving structure of what was in effect a town with borders of barbed wire. On the rare occasion men escaped the camp, they never escaped the island.

Meanwhile, in Douglas, the island’s capital, a tented holiday camp had become an early prison for up to 5,000 internees. The railway proved useful for transferring most of them to Knockaloe. But wealthier “aliens” travelled in the opposite direction. “Knockaloe covered a cross-section of society, from aristocrats to the working class,” explains Matthew Richardson, a curator at Manx National Heritage, which has a museum in Douglas. “At Douglas they opened a ‘privilege camp’ where those with money could pay to live in luxury, employing other internees as servants.”

Priority was given to keeping men occupied. They tended kitchen gardens, while artists used what materials they could gather (Leece Museum in the city of Peel has a collection of left-over beef bones ornately carved to create vases). Others weaved baskets. George Kenner was a German artist who had moved to London in 1910. While interned at Knockaloe, he painted more than 100 scenes of camp life, unwittingly becoming a crucial historian of the time.

Mr Richardson says most enquiries the museum receives today concern an internee who was well-known inside Knockaloe for his unorthodox approach to fitness. The son of a gymnast from Mönchengladbach had survived a childhood beset by illness to become a bodybuilder and boxer. He moved to Britain in 1912 and trained police officers in self-defence. During his internment, he developed a yoga-inspired exercise that required only a mat, a technique he developed further after the war when he emigrated to America. His name was Joseph Pilates.

Knockaloe included a post office and even printing equipment, which inmates used to publish five camp magazines. One elaborately illustrated journal was called Quousque Tandem – a Latin phrase meaning “for how much longer?” Mr Richardson’s team has only recently set about translating the pages. “I think in post-war years it carried a stigma to have been interned, so a lot of people didn’t talk about it,” he says. “You can count on one hand the number of published personal accounts.”

Historians say Britain has been equally reluctant to face up to the policy – essentially organised xenophobia – for different reasons. While rarely questioned in the heat of war, the treatment of Germans inside and outside camps has been criticised since. The majority of those interned fled Britain after the war or were deported. Many never saw their families again. As the historian Richard Dove wrote in 2005, internment “brought little discernible benefit to Britain [and] cruelly damaged the lives and livelihoods of those detained, breaking up families and disrupting social networks. It resulted in the destruction of German communities in Britain, which suffered a blow from which they never recovered.”

Tomorrow: A poet in the trenches

The '100 Moments' already published can be seen at: independent.co.uk/greatwar

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments