For free real time breaking news alerts sent straight to your inbox sign up to our breaking news emails Sign up to our free breaking news emails

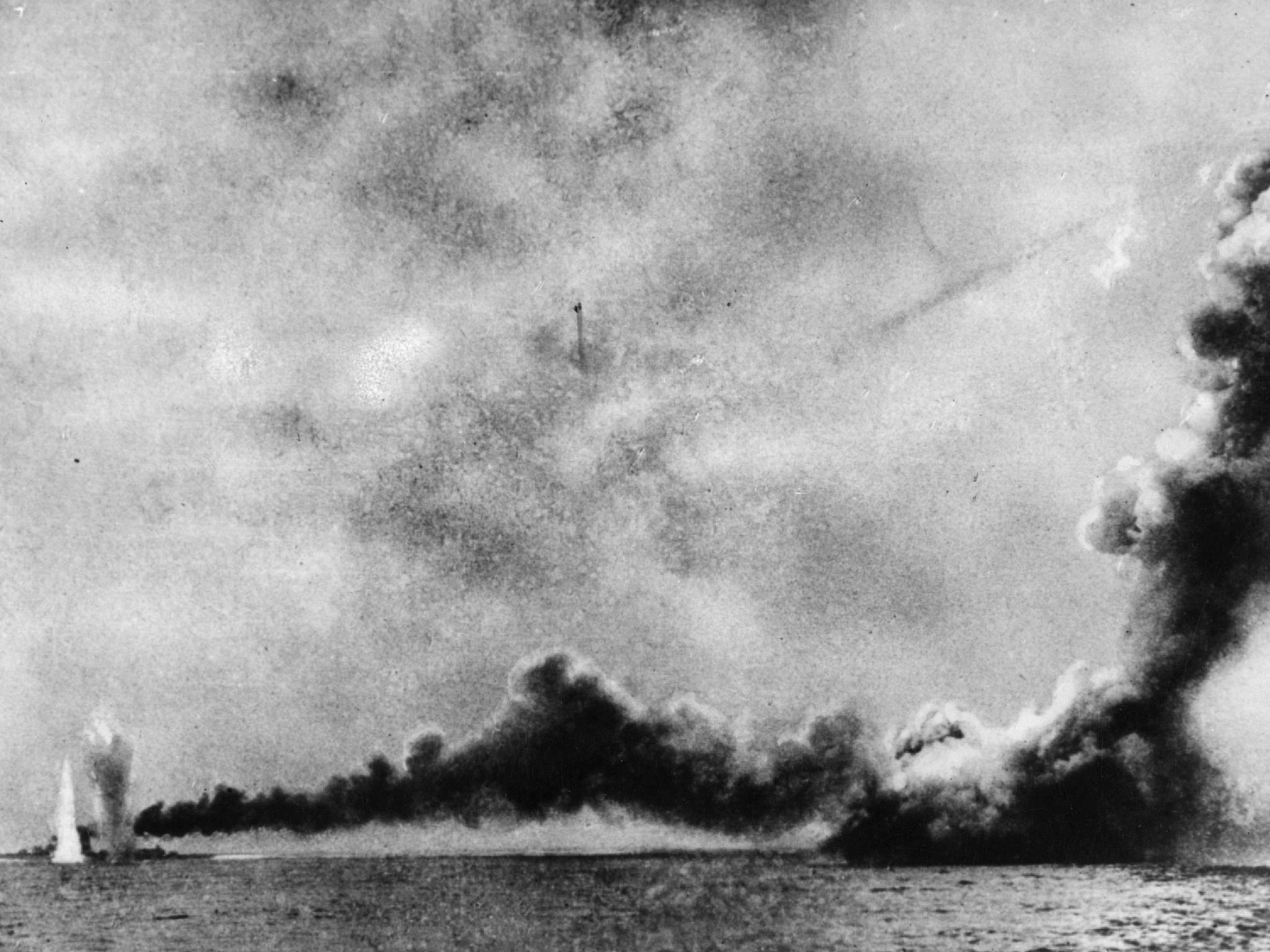

At about 4.25pm on 31 May 1916, the HMS Queen Mary, the most advanced battlecruiser in the Royal Navy, disintegrated under brutally accurate German gunfire.

“First of all a vivid red flame shot up from her forepart,” wrote Commander Georg von Hase, gunnery officer aboard the Derfflinger, one of two German ships which were attacking her. “Then came an explosion forward which was followed by a much heavier explosion amidships… and immediately afterwards the whole ship blew up with a terrific explosion. Finally nothing but a thick, black cloud of smoke remained where the ship had been.”

Petty Officer Ernest Francis was one of only nine members of Queen Mary’s crew of 1,275 to survive. “I struck away from the ship as hard as I could,” he recalled. “I must have covered nearly 50 yards when there was a big smash, and stopping and looking around, the air seemed to be full of fragments and flying pieces.”

The Queen Mary was one of three British battlecruisers to blow up during the Battle of Jutland, which was fought roughly 300 miles east of Aberdeen and 50 miles west of the Danish coast on 31 May to 1 June 1916.

Show all 149 1 /149In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Supporting troops of the 1st Australian Division walking on a duckboard track near Hooge, in the Ypres Sector

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Final moments: The Archduke of Austria Franz Ferdinand with his wife Sophie in Sarajevo minutes before his shooting

AP

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Arresting Princip’s fellow conspirator Nedeljko Cabrinovic after a failed attempt to kill the Archduke on the same day

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Crowds in central London cheer Britain’s declaration of war on Germany

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War The innocents: New recruits, with bicycles, training with the British Army in 1914

Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War 1914: A lone soldier with a bicycle stands amid the remains of a German motor convoy which lines a country lane after an attack by French field guns in the battle of the Aisne in France

Topical Press Agency/Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Troubled waters: The Cambridge eight included John Andrew Ritson (fourth from cox)

Museum of London, Christina Broom

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War John Andrew Ritson (left)

Museum of London, Christina Broom

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Dennis Ivor Day

Musuem of London; Christina Broom

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War German infantry advance through Belgium in August 1914

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Civilians near the Austrian lines in Serbia are strung up – probably as a reprisal for guerrilla resistance to the invaders

Miroslav Honzík/Hana Honzíková

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Captured soldiers of the Russian 2nd Army after their defeat at the Battle of Tannenberg

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Wounded and exhausted British and Belgian soldiers retreating after the Battle of Mons

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Crowds gather outside a recruitment office

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War French General Joseph Joffre (second right), Commander- in-Chief of the French Armies, and General Michel Joseph Maunoury (right) on the front during the First Battle of the Marne. Six hundred scarlet taxis were requisitioned, at a cost of Fr70,102, to ferry reservist troops to the Battle of the Marne in 1914

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War A French firing squad escorts a deserter to his execution in November 1914

Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War One of the trenches from which deserters tried to escape

Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War German soldiers in Wirballen, a border town between the German Reich and Russia

Mary Evans Picture Library

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Carl Hans Lody, who spied in Britain

Popperfoto/Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Up to 12 million letters a week were sent to the front line via the wooden sorting office hastily set up in Regent’s Park in 1914

Royal Mail

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Survivors from SMS ‘Gneisenau’ in the sea off the Falkland Islands, with HMS ‘Inflexible’ in the background, 8 December 1914

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War The ruins of the cloth hall and cathedral in Ypres during WWI

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Margot Asquith, the Countess of Oxford and Asquith and the wife of Britain’s wartime leader

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War A wounded American in a London hospital reads a magazine with a red cross nurse by his bedside.

A. R. Coster/Topical Press Agency/Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War A mass execution by firing squad following the unsuccessful Singapore mutiny of 1915

rebelsindia.com

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Indian soldiers serving in France were known for their fighting spirit

Underwood Archives/Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Russian artillery positions outside Przemysl, during the six-month siege of the heavily fortified Austro-Hungarian city, part of present-day Poland

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Residents assess the damage after Suffolk was rocked by bomb attacks mounted by German Zeppelin

Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War German infantrymen attack through a cloud of poison gas. By the end of the war, both sides had employed various kinds of gas

Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Children of Armenian refugees in a camp

Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Armenian civilians being led away by Ottoman soldiers

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War A public hanging in Istanbul

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War A pile of skulls from the Armenian village of Sheyxalan

AFP/Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Allied troops at Anzac Cove (Gaba Tepe) during the Gallipoli campaign

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Allied troops unloading heavy guns in the Dardanelles

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Volunteer nurse Florence Farmborough was part of the Russian retreat from Gorlice

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Cunard liner RMS Lusitania, after secret Whitehall misgivings about the official account of one of the most controversial and tragic episodes of the First World War were revealed in newly-released government documents. Almost 70 years after the Cunard liner RMS Lusitania was sunk by a German U-boat off the coast of Ireland, some officials expressed concern that the truth was still being covered up

PA Wire

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War The RMS Lusitania sailed from New York on 1 May 1915 on her last voyage; the liner was sunk off southern Ireland on 7 May

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Welsh Liberal politician and future Prime Minister David Lloyd George (1863 - 1945) enjoys a quiet read of a newspaper in his garden with his faithful dog for company

Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War French troops line up for inspection on a trench on the Western Front

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War German military prisoners, at Southend-on-Sea, on their way to Knockaloe

Print Collector/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War The railway line running the length of the access road into Knockaloe, the biggest camp in the British Isles

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Survivors of the sinking in Cobh, Co Cork

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Robert Graves (1895-1985), who served on the Western Front from 1915 to 1917

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War 2nd Lieutenant John Kipling is thought to have been killed in The Chalk Pit, in Loos, France, on 27 September 1915

Wikimedia Creative Commons

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Laid to rest: Edith Cavell circa 1905

Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Her funeral cortege in London in May 1919

Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War George Samson is celebrated on a cigarette card of the time

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Flora Sandes, who rose from private to sergeant-major in the Serbian army, playing chess with her Serbian comrades. After the war ended, she was promoted to lieutenant

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Italian light infantry of the 1st Alpini Regiment on Monte Nero, during the Isonzo campaigns

Universal History Archive/UIG/Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War As Italian as mozzarella cheese: Giuseppe Ungaretti

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War French troops under shellfire during the Battle of Verdun

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War A French soldier is shot during a counter attack

Alamy

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Devastation near Fort Souville, Verdun

Alamy

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Conscripts, among the first men ever to be compelled to join the British Army, undergo a medical

Central Press/Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Chandeliers and bed rest

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War The Pavilion was meant as a seaside home for the Prince Regent

Royal Pavilion and Museums, Brighton & Hove

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Fun and games were vital

Royal Pavilion and Museums, Brighton & Hove

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Patients get some sea air

Royal Pavilion and Museums, Brighton & Hove

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War The medical staff

Royal Pavilion and Museums, Brighton & Hove

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Britain saw the Easter Rising as a stab in the back and the rebels, pictured here being led to captivity, as traitors. Subsequent executions made them into national heroes

Rex

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War A steamer hit by a torpedo during the First World War

Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War The Ottoman army besieged the British forces for 147 days until they surrendered on 29 April 1916

Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War General Sir Charles Townshend

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War The tear-stained letter

Imperial War Museum

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Siegfried Sassoon as a second lieutenant in the Royal Welch Fusiliers. His bravery won him the Military Cross in July 1916, but he later turned against the war

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War The sinking of the ‘Queen Mary’

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Admiral John Jellicoe, commander of the British fleet

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War German destroyers off the English coast

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War One of the architects of the revolt: Sharif Hussain, religious leader of Mecca

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War One of the architects of the revolt: Sir Henry McMahon, British minister in Cairo

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Emilio Lussu, who fought in the battle with the Italian Army, on the side of the allies, against the Austrians, who sided with Germany

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Field Marshal Horatio Herbert Kitchener, whose face appeared on the recruitment poster ‘Your Country Needs You’

Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Conscientious objectors at a protest on Dartmoor in 1917

Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Objectors were forced to cultivate the soil although many were said to have spent much of their time "strolling on the moors, reading, smoking and talking"

Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War British conscientious objectors leaving Dartmoor Prison under a gateway inscribed with the words "Parcere subjectis" ("Spare the conquered")

Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Going over the top during the Battle of the Somme in 1916

PA

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War The British Machine Gun Corps during the battle

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Canadian troops prepare for the charge

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Remains of the German airship shot down over Cuffley

Popperfoto

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Captain William Leefe Robinson received the VC for his courage

Hulton/Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War A British Mark 1 tank on the Western Front

Topical Press/Hulton/Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War A British soldier covers a dead German on the firestep of a trench near the Somme

Hulton/Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Carnage on the road to Romania’s Turnu Rosu Pass. A German NCO stands beside an Italian-made cannon and the body of what may have been a gun crew member

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Edward Thomas, a Second-Lieutenant in the Royal Garrison Artillery, at home on leave in early 1917

Edward Thomas Fellowship

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Edward’s wife Helen with two of their three children, Merfyn and Bronwen

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War May Bradford writing a letter for an injured soldier in a French hospital

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Composer and poet Ivor Gurney (left) and the artist Paul Nash

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Filling shells at the Vickers munitions factory, Barrow-in-Furness. Strikers’ grievances included the use of female labour

BAE Systems Submarines

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War The moment that ushered in the American century: President Woodrow Wilson asks Congress to ratify a declaration of war against Imperial Germany

AP

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Supporters greet Lenin on his arrival at Finland Station, Petrograd, on 16 April 1917, after a week-long journey by sealed train from Switzerland

Everett Collection/Rex Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War War effort: Women war workers at Cross Farm, Shackleton, Surrey, in 1917

Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War French ‘poilus’ at Chemin des Dames, where the bloody Nivelle Offensive of 1917 pushed many into mutiny

Rex

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War An early colour photograph of the crater left by the biggest of the blasts beneath German positions near Messines on 14 June 1917

Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War British sappers laying the mines

Heritage Images/Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War The remains of a German trench

Alamy

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Ernst Jünger’s German platoon overcame the enemy forces with his ‘mastery of the situation and iron command’

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Siegfried Sassoon was sent to Craiglockhart Hospital to be treated for ‘shell shock’ following his protest

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Erich Maria Remarque (1898-1970), whose 1929 novel, ‘All Quiet On The Western Front’, was based on his wartime experiences. Here he is seen with Carl Laemmle of Universal Pictures (left)

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War The conscription of reserve soldiers in Greece to fight on the Salonika front in 1916. The Greek city was ravaged by a fire the following year, which devastated the area and left thousands homeless

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Allied troops marching down the Boulevard de la Victoire in Salonika in 1916, the year before the great fire which devastated the Greek city

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Women leaving a munitions factory on Eiswerder Island in Spandau, near Berlin, at the end of their shift, in around 1917. They are crossing the bridge over the river Havel

TopFoto

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Female workers of the Spandau factory getting their dinner during the midday break

TopFoto

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Wet weather plagued the Third Battle of Ypres, which included the battles of Langemarck and Passchendaele. Perhaps 70,000 Allied soldiers died between 31 July and 10 November

Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War A British stretcher party

Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War German prisoners on a duckboard track at Yser Canal, Belgium, on the opening day of the battle

Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War 3rd September 1917: Veterans of the American Civil War at the opening of the Eagle Hut

Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War US Ambassador Page greeting veterans of the American Civil War at the opening of the Eagle Hut

Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War 22nd December 1917: Christmas preparations at the Eagle Hut

Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Albin Köbis, who was shot as one of the ringleaders of the German naval mutiny in 1917

Alamy

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Stokers of the SMS Prinzregent Luitpold in 1913

Alamy

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Allied troops in what is now Zambia, in vain pursuit of the forces of the elusive German general Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Genius in the art of bush warfare: German general Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck

Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War German women and children queue for food rations

Alamy

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Crowds at Petrograd’s Winter Palace during the October Revolution. (Russia still used the Julian calendar, in which the West’s 7 November equated to 25 October)

Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War The Mayor of Jerusalem (with walking-stick) had tried to surrender the city to them

Imperial War Museum

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Allenby walks into Jerusalem: Sergeants James Sedgwick and Frederick Hurcomb of 2/19th Battalion, London Regiment, outside the city two days earlier

AP

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Artist John Nash not only painted the ordeals of Britain’s front line troops: he experienced them first-hand

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War A British housewife with her grocery items after the introduction of rationing. The government feared hunger might lead to revolution

Rex

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Edmund Morel as an MP after his release

Topham Picturepoint

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War A suffragist rally in Hyde Park

Hulton/Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War A newly enfranchised woman votes for the first time in 1918

Hulton/Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Masked doctors and nurses treat flu patients lying on cots and in outdoor tents at a hospital camp during the influenza epidemic of 1918

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War The immense long-range naval gun which was used to bombard Paris from behind the German lines in Picardy

TopFoto

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War The immense naval gun was manned by 80 German sailors. It launched its shells from behind the German lines

TopFoto

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Walter Tull, left, Britain’s first black Army officer, in a photograph handed down to his great-nephew Edward Finlayson

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Tull was singled out for his "gallantry and coolness" following a daring raid across the frozen river Piave in January 1918

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War The German air ace Baron Manfred von Richthofen

Hulton/Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Baron Manfred von Richthofen's 'flying circus'

Hulton/Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Dogs at the British War Dog School in Essex

Mary Evans Picture Library

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Tweed, far left, with his handler Private Reid

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War A dog courier runs through barbed wire and mines to deliver a message

Corbis

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Piete Kuhr, pictured in 1915

Memoria Hürth

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Vera Brittain became a nurse during the war

Hulton/Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War The aftermath of the explosion at the munitions plant in Chilwell

Nottingham City Council

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Remains of a soldier on the Western Front, where millions were killed or wounded, or went missing

Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War From left, Marshal Joffre, President Henri Poincaré, King George V, General Foch, and Field-Marshal Haig

Time life pictures/Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Captured German officers receiving orders from a French officer

Universal Images Group/Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War American troops advance on a German position on the Saint Mihiel salient, north-eastern France, in 1918

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War American soldiers of the 18th Infantry Machine Gun Battalion advance through the ruins of St Baussant on their way to the St. Mihiel Front

Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War A group of captured Germans being marched through St Mihiel Salient

Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Wilfred Owen in uniform as a 2nd Lieutenant. The poet was teaching in France when the war began

Fotosearch/Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War The poet Rainer Maria Rilke, circa 1920. The poet describes to his wife the rising tide of popular unrest in Munich

Hulton/Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War The interior of the railway carriage in which the Armistice ending the First World War was signed

Hulton/Getty

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War The Allied delegation was led by France’s Marshal Ferdinand Foch (front row, second right)

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War The Royal Family appear on the balcony

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War People celebrate in the streets in 1918

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Crowds in London celebrate the end of hostilities on 11 November 1918

Getty Images

In pictures: A history of the First World War in 100 moments First World War Crowds in London celebrate the end of hostilities in 1918

Getty

A battlecruiser was broadly the same as a battleship but faster and less heavily armoured. In all three cases, weaknesses in design and carelessness in the management of explosives allowed the flash from German shell-strikes to penetrate the British ships’ magazines and destroy them with their own unused ammunition.

Jutland was the first and last fleet action of the war. It was only the third large battle to be fought by steel-clad warships. It was the only battle ever fought by large numbers of “dreadnoughts” – the large, heavily armoured and heavily armed warships invented by Britain in 1906.

The arms race between Britain and Germany to build dreadnoughts was one of the principle causes of tension between the two countries in the years before the war. Unless the Royal Navy maintained a significant lead, the hawks argued, Britain would be invaded or strangled by a German blockade.

The ill-fated HMS Queen Mary, commissioned in 1913, was one of the products of a shrill political and press campaign for “more dreadnoughts” during a period of acute suspicions of German ambitions around 1910–11.

Jutland was a great disappointment to the British, who had been nourished on tales of crushing naval victories over the French a century earlier. The Royal Navy lost 14 ships to the German navy’s 11. Britain lost 6,784 men, Germany 3,039. On the other hand, the badly battered German fleet fled for home and never ventured en masse into the North Sea again before surrendering in 1918.

The outcome was shaped by industrial strengths as well as military ones. The German ships were tougher. The British gunnery was excellent but the Royal Navy’s shells were often too weak to penetrate the heavy German armour. Many of the British shells were duds (just as they were at the battle of the Somme, one month later).

“Next morning: It has now become a victory.”

Who was right?

Strategically, Jutland maintained the status quo – the dominance of the Royal Navy and the maritime blockade of Germany. As one American journalist wrote at the time, the Hochseeflotte (High Seas Fleet) had “assaulted its jailor but it remains in jail”.

The German navy had planned to lure the British fleet from its bases in Orkney and the Firth of Forth and reduce its numerical superiority by submarine attacks and mines. The Admiralty could read the German naval codes and knew that the Hochseeflotte was preparing for sea.

The British Grand Fleet, under Admiral John Jellicoe, left Scapa Flow, before the German fleet sailed under Vice-Admiral Reinhard Scheer. A smaller force of British battlecruisers and last battleships under Admiral David Beatty, sailed from the Firth of Forth and made the first contact.

The Royal Navy ships were still largely communicating with flags, as they had at Trafalgar. The Germans successfully used wireless. Unseen flags and other miscommunication divided Beatty’s force. He lost two battlecruisers, including the Queen Mary, as he pursued what he assumed was a smaller German force to the south.

He found that he had been drawn into the entire German fleet. He turned tail and fought a running battle, drawing the whole of the German navy into the massed ranks of Jellicoe’s dreadnoughts.

Twice, Jellicoe achieved the tactical advantage of “crossing the T” – sailing his fleet, all guns bearing, across the head of the German line. Twice, using their superior communications, the Germans turned away in perfect formation.

German destroyers off the English coast (Getty Images) Jellicoe’s fleet was forced to manoeuvre to avoid a volley of torpedoes. The Germans escaped his clutches in the dark and sailed for home. Jellicoe was much criticised for turning away from the torpedoes and allowing the Gemans to escape. This was unfair. He had, at all costs, to preserve his fleet.

A British victory would have changed little; a German victory would have changed everything. As Winston Churchill had said, Jellicoe was the “only man who could lose the war in an afternoon”.

Despite their claims of victory, the German navy and high command accepted, de facto, that Jutland had been a failure. They rapidly switched to unrestricted submarine warfare against all merchant ships, allied and neutral. This strategy almost won the war before the admiralty reluctantly started to organise convoys. It also guaranteed Germany’s ultimate defeat by outraging public opinion in the US.

What Jutland proved – though naval strategists were slow to grasp the lessons – was that the dreadnought was already a clumsy and obsolete weapon. Most future naval battles would be decided by submarines and aeroplanes.

Many of the 34 British dreadnoughts which survived Jutland never fought again. They were scrapped between the wars. The 20 surviving German dreadnoughts were surrendered in 1918, interned at Scapa Flow in Orkney and scuttled by their crews in June 1919, almost exactly three years after Jutland.

Most, including the Derfflinger, were later raised for scrap. Seven remain to this day below the beautiful, placid water of Scapa Flow. They have become a popular deep-sea diving destination.

Tomorrow: The Arab Revolt begins

The '100 Moments' already published can be seen at: independent.co.uk/greatwar

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies