Allied forces knew about Holocaust two years before discovery of concentration camps, secret documents reveal

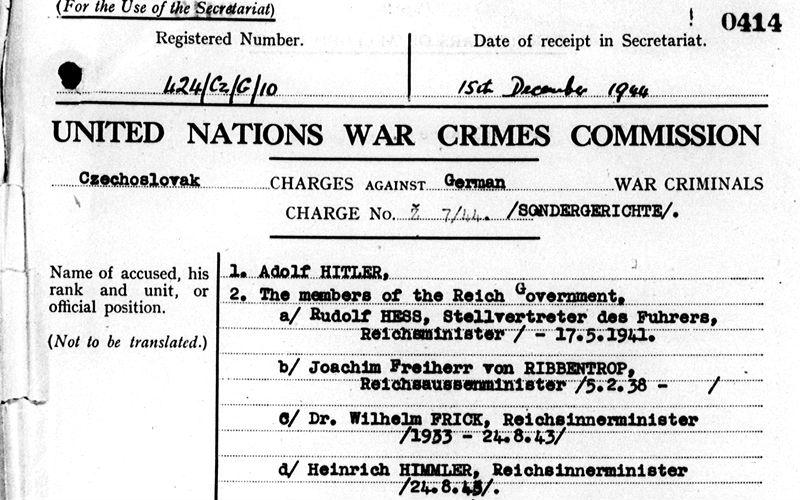

Archive shows Adolf Hitler was indicted for war crimes in 1944

The Allied Powers were aware of the scale of the Jewish Holocaust two-and-a-half years earlier than is generally assumed, and had even prepared war crimes indictments against Adolf Hitler and his top Nazi commanders.

Newly accessed material from the United Nations – not seen for around 70 years – shows that as early as December 1942, the US, UK and Soviet governments were aware that at least two million Jews had been murdered and a further five million were at risk of being killed, and were preparing charges. Despite this, the Allied Powers did very little to try and rescue or provide sanctuary to those in mortal danger.

Indeed, in March 1943, Viscount Cranborne, a minister in the war cabinet of Winston Churchill, said the Jews should not be considered a special case and that the British Empire was already too full of refugees to offer a safe haven to any more.

“The major powers commented [on the mass murder of Jews] two-and-a-half years before it is generally assumed,” Dan Plesch, author of the newly published Human Rights After Hitler, told The Independent.

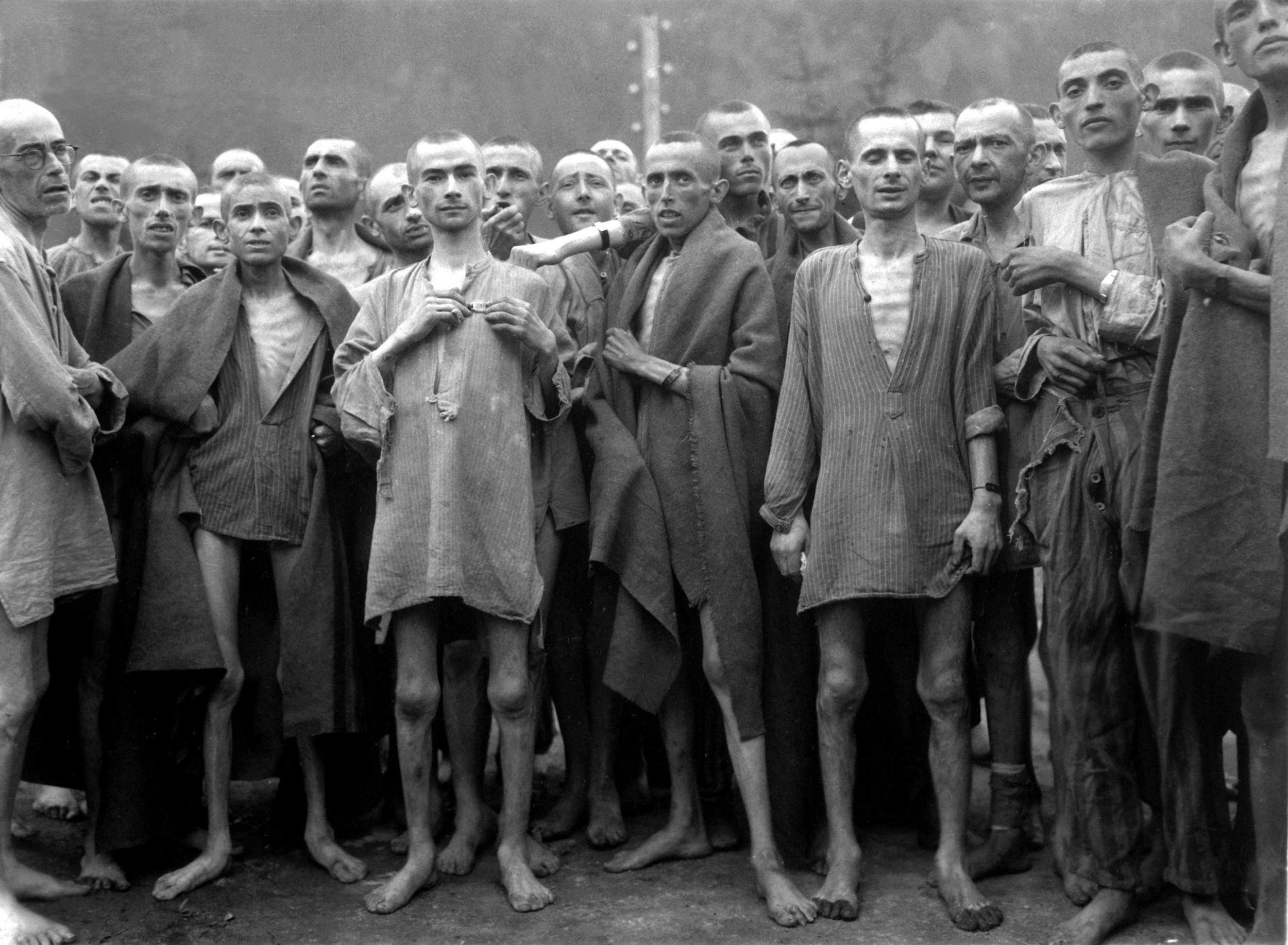

“It was assumed they learned this when they discovered the concentration camps, but they made this public comment in December 1942.”

Mr Plesch, a professor at the Centre for International Studies and Diplomacy at SOAS University of London, said the major powers began drawing up war crimes charges based on witness testimony smuggled from the camps and from the resistance movements in various countries occupied by the Nazis. Among his discoveries were documents indicting Hitler for war crimes dating from 1944.

In late December 1942, after the US, UK and others issued a public declaration about the Jewish slaughter, UK Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden told the British parliament: “The German authorities, not content with denying to persons of Jewish race in all the territories over which their barbarous rule extends, the most elementary human rights, are now carrying into effect Hitler’s oft-repeated intention to exterminate the Jewish people.”

Mr Plesch said that despite the collection of evidence and the prosecution of hundreds of Nazis – a judicial process that has been overshadowed by the trial of the Nazi leadership at Nuremberg – the Allied Powers did little to try and help those in peril. He said efforts by President Franklin D Roosevelt’s envoy to the United Nations War Crimes Commission (UNWCC), Herbert Pell, were pushed back by anti-semites in the US State Department.

Mr Pell would later claim that individuals within the State Department were concerned that America’s economic relationship with Germany after the war would be damaged if such prosecutions went ahead. After Mr Pell went public with the scandal, the State Department agreed to the prosecution of the Nazi leadership at Nuremberg, something that gathered pace after the highly publicised liberation of the concentration camps in the summer of 1945.

“Among the reason given by the US and British policy makers for curtailing prosecutions of Nazis was the understanding that at least some of them would be needed to rebuild Germany and confront Communism, which at the time was seen as a greater danger,” writes Mr Plesch.

Mr Plesch said the archive on which he based his research was closed to researchers for 70 years. Those wishing to read the UNWCC archive required the permission not only of the person’s own national government, but the UN Secretary General. Even then, researchers were for several years not permitted to make notes.

Former American ambassador to the UN Samantha Powers took the action that made the archive available.

Mr Plesch said the new material provided a further “cartload of nails to hammer into the coffins” of Holocaust denial – not that further evidence was required.

Yad Vashem, the Holocaust remembrance memorial in Israel, says on its website that “information regarding mass murders of Jews began to reach the free world soon after these actions began in the Soviet Union in late June 1941, and the volume of such reports increased with time”.

It refers to the December 1942 declaration condemning the extermination of Jewish people.

“Notwithstanding this, it remains unclear to what extent Allied and neutral leaders understood the full import of their information,” it adds. “The utter shock of senior Allied commanders who liberated camps at the end of the war may indicate that this understanding was not complete.”

The UNWCC archive is this week being presented to the Wiener Library in London, the world's oldest Holocaust archive and Britain's largest collection on the Nazi era, where it will be available for scholars to access online.

Ben Barkow, the library’s director, said Mr Plesch’s findings may not change the general understanding of the Holocaust, but were interesting and had significance to scholars.

He said Mr Plesch had doggedly continued to search a difficult-to-access archive that most scholars had assumed contained nothing new. “People didn’t recognise the value of it,” he said.

He said the material uncovered by Mr Plesch was particularly interesting because it showed that 70 years ago, the international community was considering the issue of sexual crimes as part of the broader war crimes narrative. He said: “It shows that this was not something that was only thought about after events like Rwanda.”

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks