The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Jesse Jackson: Civil rights icon who built on mentor Martin Luther King Jr’s legacy and inspired a generation

The Reverend Jesse Jackson, a towering figure in the American civil rights movement, has passed away at the age of 84. Ariana Baio looks back on his inspirational life

The Reverend Jesse Louis Jackson, the longtime civil rights leader and former politician who rose to prominence as a protege of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., has died.

The 84-year-old’s family announced his passing on Tuesday in a statement, describing him as a “servant leader... to the oppressed, the voiceless and the overlooked around the world.” No cause of death has been given.

Jackson, who had been living with Parkinson’s disease since 2017, was admitted to the hospital last November with progressive supranuclear palsy, a rare neurological disorder he had been managing “for more than a decade” but received a diagnosis for in April.

His tireless dedication to racial equality spanned more than six decades and helped shape the modern civil rights movement.

Jackson profoundly shaped American politics, inspiring a generation of minority leaders and moving the Democratic Party’s platform toward social and economic progressivism as it entered the 21st century.

He was born Jesse Louis Burns October 8, 1941, in Greenville, South Carolina, to Helen Burns, reportedly 16, and Noah Louis Robinson, a 33-year-old married neighbor. Jackson would not learn the identity of his biological father until he was seven years old.

Later in his childhood, Jackson took the last name of his stepfather, Charles Jackson, whom his mother married when he was an infant. Jackson considered both men to be his fathers.

Growing up in poverty in the Jim Crow era, facing societal judgement for being born out of wedlock and personal challenges with his biological father, Jackson learned to channel his fears into excellence.

“I was afraid to fail,” Jackson told the Chicago Tribune in 1996. “An all-around excellence in sports and academics, being a first-string athlete and an honor student, could protect you from feeling a certain form of rejection. People don’t laugh at you when you get A’s.”

From his early adolescence, Jackson was defined by his charisma and intelligence, being elected class president of Sterling High School and graduating with honors.

Jackson rejected an offer from a minor league baseball team and instead took a football scholarship at the University of Illinois. He later transferred to North Carolina A&T State University.

While attending A&T, Jackson became active in the civil rights movement, joining his local Congress of Racial Equality chapter and taking a leadership role in organizing sit-ins.

Among those was a sit-in Jackson organized on July 16, 1960, at the “whites only” Greenville County Public Library, which would later land Jackson and seven other Black students with the nickname the “Greenville Eight.”

After Jackson was turned away from the library while attempting to acquire a book for a school report, he and the other Black students entered the library and read quietly. When they refused to leave, they were arrested.

As a result of the Greenville Eight’s sit-in, the library closed down its segregated branches and later opened a single integrated one.

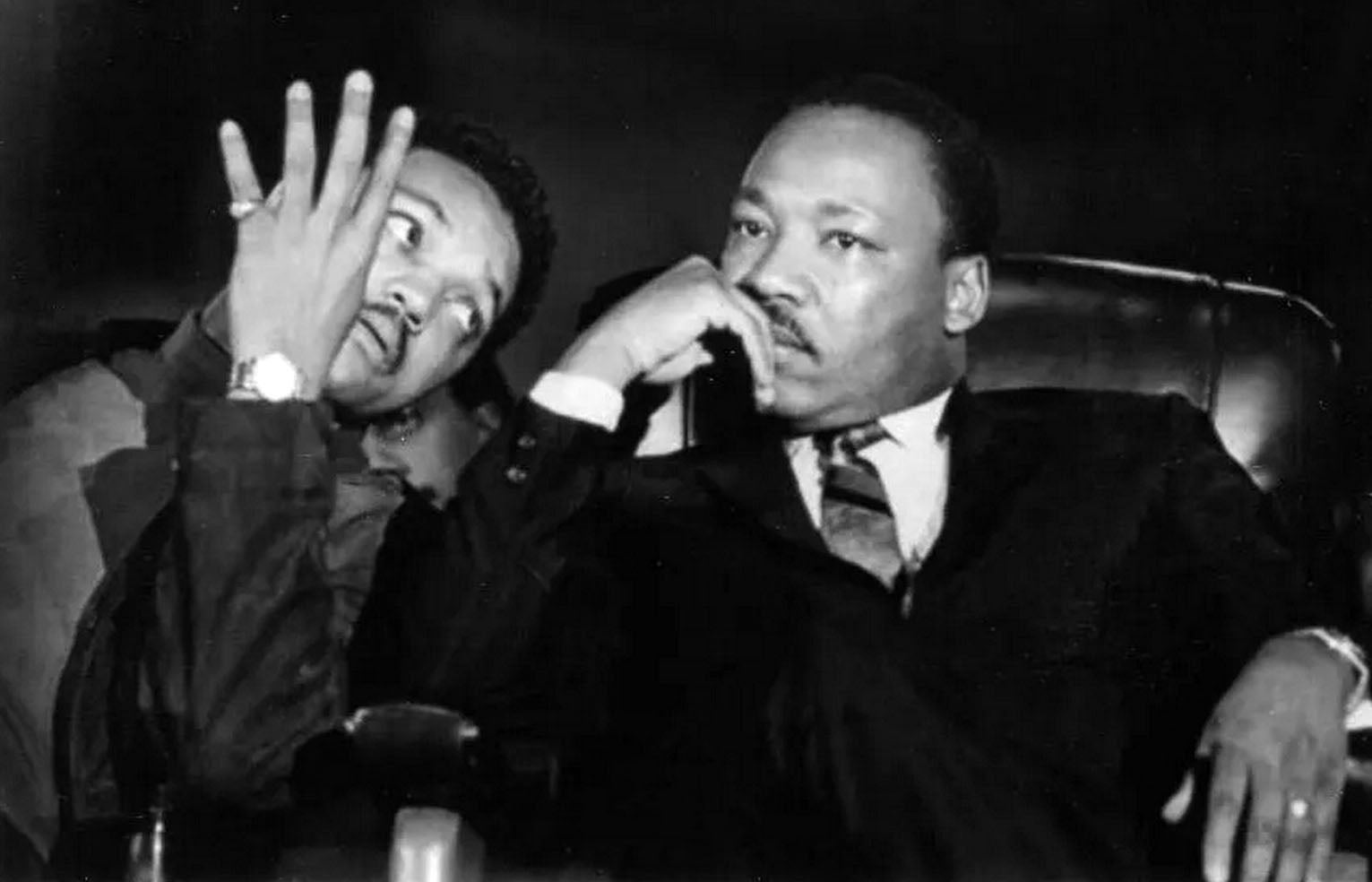

It was then that Jackson attracted the attention of King.

Jackson began studying theology at the Chicago Theological Seminary, but deferred to work full-time with King during the civil rights movement. He was ordained a minister in 1968 and was later given a Master of Divinity from the school in 2000.

King recruited Jackson to be an organizer with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and soon appointed him director of the Operation Breadbasket program, dedicated to improving the economic conditions of Black communities.

Jackson had a magnetic ability to capture a room through his persuasive and engaging speeches. He was known for reciting a call-and-response chant, known as “I Am Somebody,” which encouraged people to uplift themselves.

Through his speeches, Jackson energized thousands of people to boycott businesses that refused to hire qualified Black Americans.

“We have been the nation’s laborers, her waiters,” Jackson said during a 1968 Operation Breadbasket meeting.

“Our women have raised their presidents on their knees,” he said. “We have made cotton king. We have built the highways.

“We have died in wartime fighting people we were not even mad at. America worked us for 350 years without paying us. Now we deserve a job or an income.”

The success of the movement led to the creation of 4,500 jobs in Chicago alone and millions in income for Black communities.

At 27, Jackson was a rising voice in the civil rights movement, considered a contender to become King’s successor. But the assassination of King changed the future of the SCLC and Jackson’s position in it.

On April 4, 1968, Jackson was on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis when King was fatally shot.

“Every time I think about it, it’s like pulling a scab off a sore,” Jackson said of King’s assassination in a 2018 interview with The Guardian.

“It’s a hurtful, painful thought: that a man of love is killed by hate; that a man of peace should be killed by violence; a man who cared is killed by the careless.”

King’s assassination left SCLC’s leadership fractured, and after a falling out with its new leader, Ralph Abernathy, Jackson left the organization to start his own.

The nonprofit, Operation People United to Save Humanity, or PUSH, began in 1971. Jackson later merged the organization with his political movement, the National Rainbow Coalition, to form Rainbow PUSH Coalition in 1996.

With PUSH, Jackson engaged Black and minority communities through politics, including voter registration initiatives.

He even pushed the Republican National Committee (RNC) to appeal to Black voters with policies that would support economic, health, education and media equality.

Throughout the 1970s and 80s, Jackson took several high-profile international trips, such as visiting Palestine to advocate for Palestinian statehood, South Africa to encourage desegregation, and Vatican City to ask Pope John Paul II to appeal to then President Ronald Reagan about refugees.

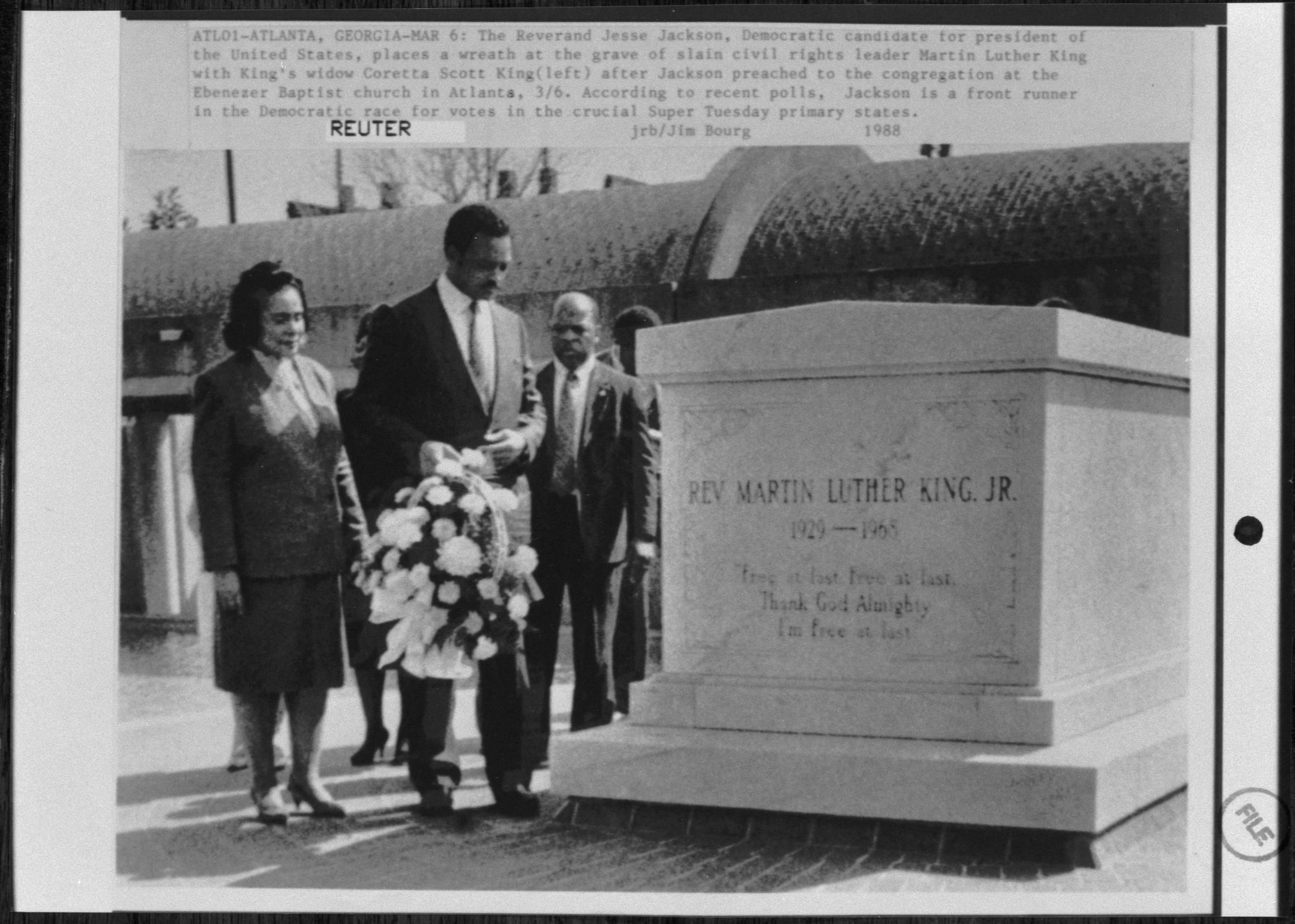

Using his political momentum from PUSH, Jackson launched what many perceived as a long-shot bid for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1984.

Campaigning on liberal policies, many of which were considered radical for the time, Jackson was largely thought of as a “fringe” candidate.

Although Jackson lost the Democratic primary, he outperformed expectations, earning 18 percent of the primary vote and winning two states.

He ran for president again in 1988, this time earning 29 percent of Democratic primary votes and winning 13 states. Despite his overall loss, his campaigns were historic, becoming the first Black candidate to win the nationwide Democratic youth vote.

“So many leaders of the African-American community have come from that campaign. He was the one,” Tina Flournoy, the ex-chief of staff to former Vice President Kamala Harris, told Politico in 2007.

Jackson maintained a powerful political figure throughout the 1990s and 2000s, albeit not in an official capacity.

From 1991 until 1997, Jackson served as D.C.’s “shadow senator,” an unofficial, unpaid position with no voting power in Congress that is primarily focused on advocating for D.C.’s statehood.

Jackson declined to run for president a third time, though former President Bill Clinton enlisted Jackson’s support to help win over Black voters.

Jackson hesitantly supported Clinton, the pair publicly butting heads on several occasions, and Jackson later served as a special envoy for democracy and human rights in Africa under his administration.

Jackson later endorsed former President Barack Obama, who went on to become the first Black president, in 2008.

In a now-famous moment, Jackson was seen with tears in his eyes as Obama made his acceptance speech in Grant Park, Chicago.

“You know, I was crying. We saw on the screen that he had won. And I thought about the moment. The movement.

“Those who could not make it to Chicago. The people who made that night possible – they were not there. They couldn’t make it,” Jackson said of Obama’s winning night to Vanity Fair in 2020.

“I wish they could have been there. Dr. King and Medgar Evers and Fannie Lou Hamer. People who’d paid the supreme price,” he said. “If God had let them live just 15 seconds more to see the fruits of their labor.”

In 2017, Jackson was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. He stepped down as the leader of Rainbow PUSH Coalition in 2023.

Although Jackson was largely out of the spotlight in the later years of his life, he remained a central figure in encouraging people to stay active as the Black Lives Matter movement progressed.

“We cannot give up the country, we cannot let darkness cast shadow on our light. We must see our way through this,” Jackson said in a 2021 interview with CNN. “Racism is unscientific. There’s no science for a superior race or inferior race.”

Jackson is survived by his wife, Jacqueline and his six children.

Jesse Louis Jackson, born October 8, 1941, died Tuesday, February 17, 2025

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks