England’s lop-sided system smothers Denmark as Bukayo Saka exposes Jannik Vestergaard

Gareth Southgate’s decisions were vindicated and his switch to a back three in extra time was simply another reminder of how flexible this team is

Three years ago England reached the semi-finals of the 2018 World Cup in Russia with one fixed wingback system. There was no alternative, no plan B, and when it came unstuck, as it did against Belgium and Croatia, Gareth Southgate had nowhere to turn.

In the intervening period Southgate and his assistant Steve Holland have developed a team with the ability to shapeshift, to confront and confound any given opponent. England could have gone with a back three and wing-backs to match Denmark’s system on Wednesday night, as they did successfully to beat Germany, but here Southgate decided to go on the front foot and ask the Danes if they could live with England’s more attacking approach. Before kick-off Gary Neville voiced his concerns over that move, saying it made him “nervous”, but Southgate was vindicated within minutes.

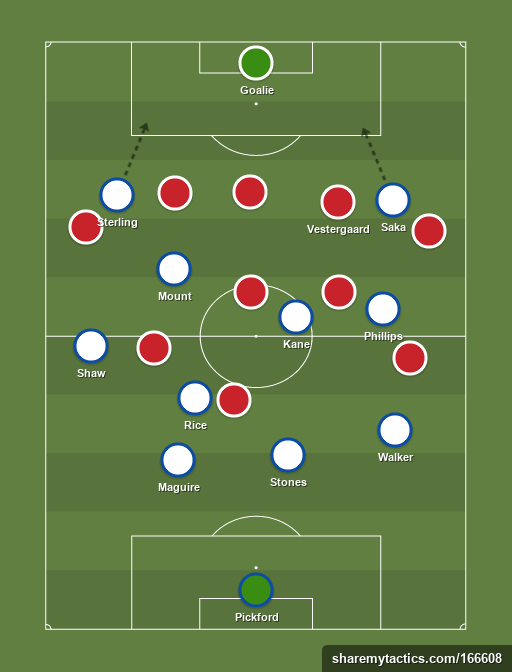

England’s back-four system can be hard to pin down at times and looks very different with and without possession, but it is broadly a lop-sided 4-2-3-1 where Luke Shaw is more advanced than Kyle Walker, Declan Rice is more cautious than Kalvin Phillips, and Raheem Sterling drives at the heart as Bukayo Saka sneaks around the sides. At Wembley it quickly became clear that the system was overwhelming Denmark through sheer attacking numbers. At times Rice picked up the ball and looked forwards to see the Danish defence pinned back with Shaw and Saka as England’s wingers, Mason Mount and Sterling as the central forwards, and Harry Kane dropping in at No 10 with Phillips in support.

Shaw’s forward runs helped to occupy the Danish right wing-back Jens Stryger Larsen, leaving Rice to fill the left-sided space from where he directed spells of possession and maintained pressure. The only early problem came when Denmark built from the back and Stryger Larsen lurked in between Sterling, who was pressing high, and Shaw in defence. Denmark’s central defender Simon Kjaer fed Stryger Larsen and Shaw pressed too late; within seconds Denmark were out and in behind England’s defensive line, requiring a recovery run from Walker to avert the danger.

Walker’s role was another benefit of the back four. He used his pace from right-back to cover his centre-halves on a couple of occasions, but just as significant was his speed out on the touchline where he nullified Denmark’s left wing-back Joakim Maehle, one of the tournament’s standout players. Denmark’s wing-backs were kept busy on defensive duties and effectively formed a back five, so England were able to outnumber their opponents in midfield and the game’s pattern was formed: England smothered as Denmark were held down and tried to resist.

Denmark struggled to get a foothold in open play but their innovative set-pieces did cause England problems, and ultimately earned the first goal. In their quarter-final against Czech Republic the Danes’ set-pieces were fairly orthodox routines but at Wembley they got creative. They crowded Jordan Pickford on the goal line from corners, and clustered tightly before deep set-piece deliveries, which helped draw the free-kick from which Mikkel Damsgaard scored. Most effectively, they created a mini-wall which shuffled sideways to screen Damsgaard’s brilliant free-kick from the sights of Pickford.

But England were undeterred by the setback of conceding a first tournament goal and stuck to their game-plan. The left flank has been England’s most potent threat during the tournament but it was on the right where they inflicted the most damage here, and two chances came in quick succession down that side. First Saka collected the ball on the right touchline, where he spent most of the match, and drove forwards before feeding a pass in behind the immobile Jannik Vestergaard. Kane collected the ball and crossed for Sterling who shot straight at Kasper Schmeichel. Then, 45 seconds later, the roles reversed: this time Saka ran in behind Vestergaard and Kane dropped deep, swivelled and quickly played him in. In a tournament of own goals, Saka forced yet another.

If anyone had any doubt over Saka’s selection he demonstrated why he was in the team. He makes runs in behind defenders more naturally than Jadon Sancho and Jack Grealish in particular, who prefers the ball to feet, and it is another sign of the strength of the squad and its tactical flexibility that Southgate has been able to pick specific weapons for certain opponents. Saka’s acceleration and intelligent movement could again be key to hurting Italy’s 36-year-old left-sided centre-back Giorgio Chiellini and stand-in left-back Emerson Palmieri in the final on Sunday.

At half-time in extra time, Southgate changed formation. Kieran Trippier replaced Grealish and England switched to three at the back. It probably made little difference to the outcome as Denmark were totally spent, but it was a final tactical flourish, perhaps just because he could. England were stuck in one formation three years ago in Russia. Here they have been able to flip shape and personnel depending on the challenge, and it has been a key reason for their ability to overcome every obstacle so far.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks