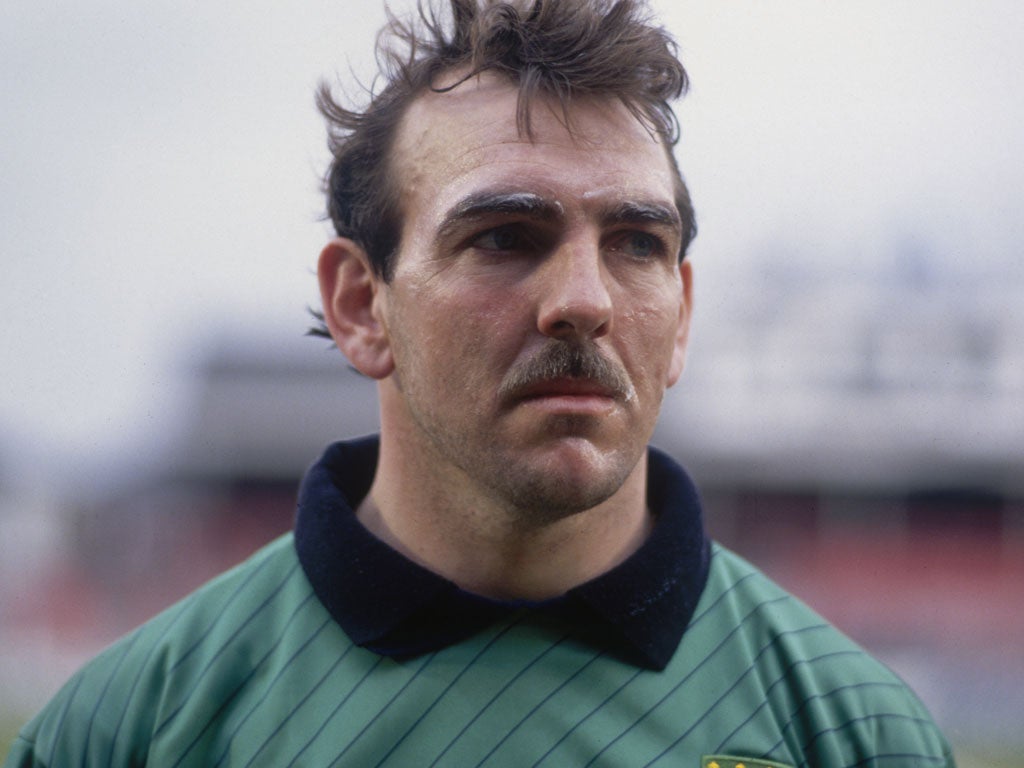

'Binman' Neville Southall still helps to pick up the pieces

He had a glorious career but mentoring dysfunctional youths now gives him equal satisfaction. He talks to Ian Herbert

No introduction to a Neville Southall interview can compete with the story which opens his new biography, in which a boy in a replica Chelsea top is hurling such obscene insults at the former Everton and Wales goalkeeper that he calls on the strategy he would use when the football terraces were delivering up their worst abuses. "Dickhead" and "bastard" are the polite terms but "all through my playing career one of my most important attributes was not letting people know what I thought. It's a quality I've brought into my new vocation," Southall relates. "Is that the worst you can do?" he asks the boy. "I've had 50,000 people shouting far worse things at me. Is that really the worst that you can think of?" Several exchanges later, the boy slumps off to the rest of the young men Southall is working with on a football pitch in Ramsgate. "It's a small victory and I know he could combust at any time," Neville concludes. "But today's excitement is over and we get back to work."

Southall's new vocation is teaching. After his magisterial career at Everton ended abruptly and with immeasurably less warmth than he deserved, the then 39-year-old's inner conviction that he could play until he was 50 pitched him into a nomadic, and generally unfulfilling, tour of football's outposts. But it was at one of the last of his locations, Dover, that he fell almost by chance into the role of mentoring seven children from dysfunctional or difficult backgrounds who had fallen out of mainstream education but all of whom, as he writes in his biography, "has some sort of unrealised potential and it was up to us to release it". He moved on to the Ashford Special School in Kent, developing a rapport with some very challenged children whom he doesn't mind saying were "bonkers". Then he joined an alternative curriculum company, was inspired enough by the results to take a Certificate of Education and then set up an educational consultancy specialising in working with young people not in Education, Employment or Training (NEETS, to coin the government jargon). This has been a journey into the heart of the coalition government's austerity measures – already Kent County Council has withdrawn the services Southall and others provided before Education Secretary Michael Gove, not Southall's favourite politician, recently removed more funding streams. If you'd have told Southall amid his 16 years and 750 appearances for Everton that he would have been articulating the flaws of Conservative education policy, he would have laughed in your face.

His new role has not come entirely by coincidence. He was always seen as something of the outsider – an individualist to some, a loner to others – who'd never touch a drop of alcohol, would eschew team hotels and coaches and be at a midweek ground with the kitman by 5.30pm, lost in self- absorption about the evening's job in hand. "You see the thing is I'm more like the kids than the kids themselves," he says from the temporary seclusion of a Cardiff hotel where he's about to be plunged into a book-signing session. "I'm quite scatty. I'm not neat and tidy and I don't like being enclosed by four walls. I like being outside and they're the same."

As he details the paths he has set some of his students on to – one has his own music business, another is into mainstream education, others in hairdressing and tattooing – you see what benefits Southall's own idiosyncrasies bring. The fine book he has written with James Corbett, which soars way beyond the realm of the standard football biography, sets out to revise the image of Southall – "binman, toffeman, nomad, legend, teacher" to cite some of the chapter headings – as an eccentric.

It does reveal a mind of unappreciated depths, though it ultimately reveals how what an excellent quality eccentricity actually is in the glossy, sanitised world of football. "Bonkers" is a word which features often.

The sections charting Southall's journey through the Everton years of the 1980s – as Howard Kendall takes the club to incredible places for a man one defeat from the sack and Mike Walker proves, on this evidence, to be even more disastrous than fans thought – is an excellent reminder of a narrative too good to slip away forgotten. But Southall's early years in Llandudno, North Wales, are the best bit. His formative job as a binman has always been one of the standard pieces of Southall biographical trivia, though that was a job he held for only three months and it was the sheer volume of other stuff – some of it utterly bonkers – which reveals a man of incredible energy.

Hod carrier, odd-jobber, floor cleaner: the only job Southall didn't do – postman – was the one he actually wanted. And then the council sent him and seven others off up to Llandudno's Great Orme armed with sledgehammers, crowbars, eventually drills and ultimately diggers, to smash up World War II gun emplacements. "It was hard and sweaty and we'd strip off. People were falling over and accidentally smashing each other with hammers," Southall relates. Only when an explosives expert minus several fingers arrived was the job finally done.

His love of the camaraderie is unmistakeable, just as on the mad trips around North Wales with the hapless Llandudno Swifts, for whom a 12-0 defeat was a good afternoon's work and whose spur-of-the moment tour of Dusseldorf led by his Uncle Johnny – bonkers – ended up with Southall's uncle telling him the elite German side, Fortuna Dusseldorf, wanted him to stay on and sign. He'd come equipped only with the shirt on his back and one spare pair of socks and underpants... "'Sorry Johnny, I can't be bothered,'" I said. "Johnny shrugged his shoulders. 'OK, let's go,'" he said.

The notion of Southall the misfit is thoroughly debunked, though his escape to professional football delivered an individual so serious and intent on performing that the Goodison years – fabled and gloried though they were – never seem shot through with quite the same joie de vivre.

The notion of Southall the oddball remains, though it as a source of celebration which makes you grieve for the lack of individuals like him. A message of the book is that difference is good, Southall agrees.

"Why do people think all footballers are incredibly intelligent when actually they are representative of society?" he says as he reflects on this literary effort. "You are judging Mario Balotelli by your standards and by what you do – aren't you – when you criticise him? But you're not 19. Some of the kids I've worked with will look at a door with a lock and think 'how can I unlock that?' Everybody learns differently. Thinks differently."

Wayne Rooney – unfit and scrutinised because of Sir Alex Ferguson's claim that his thigh injury is a "blessing" – falls into the same category for him. "They want to sanitise him," he says. "They want everyone to be like Gary Lineker – nice and never booked. Why do they want to do that? He's still developing as a footballer. Sometimes you can be injured for a reason, I believe. Sometimes it's to give you time to reflect on how far you've got and how you can improve. Sometimes it can be a really good time for you. I spent nine months out with my ankle and I got super-fit and I made sure that when I came back I really, really cherished what I was doing."

It is hard to imagine that anyone would have cherished the escape football offered more than Southall, who, the book reveals, read at every opportunity through his playing years. This was certainly a change from life at Ysgol John Bright, his comprehensive, where he managed to get hold of the answers to the streaming exams, copied them and spent his last two years out of his depth, regretting it. Was his reading a belated flowering of history study or literature? No. "I just read any books I could, relating to goalkeeping," he says. "Nutrition, oils, colour. Sports like weightlifting, boxing, gymnastics. Boxers and golfers have a similar mindset to goalkeepers. They just go and do what they have to do and there's no one to help them if they make a mistake. They said that Muhammad Ali trained under water and people threw stones at him..."

The book's depiction of his leaving Everton is one of genuine pathos, in which a beleaguered Kendall tells him "you do know I love you" but insists he stay away from the Bellefield training ground. "Fuck off," Southall tells him. "I just want to play." That he should have travelled to a geographical extremity – Torquay United – before finding his next fleeting contentment says it all. "I don't like going back. I get embarrassed when they ask me to walk on the pitch," he says of Goodison. "It's like walking into someone else's home." Which makes Southall's new calling seem as important to him as to those whom he is trying to teach the skills of life.

Neville Southall, The Binman Chronicles. De Coubertin books, £18.99

Goodison great: Southall’s career

Born Llandudno, North Wales, 16 September 1958.

Career Everton manager Howard Kendall bought the goalkeeper from Bury for £150,000 in 1981. Southall went on to make 578 appearances for the club in the league alone, more than any other player. He also kept 269 clean sheets in all competitions for the Toffees, still a record.

Honours won at Everton Cup Winners' Cup (1985), First Division title (1985, 1987), FA Cup (1984, 1995), League Cup (1984).

Southall is the third oldest player to start a Premier League game, when he played for Bradford City aged 41 and 178 days in a 2-1 loss to Leeds United in March 2000. Joe Lynskey

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies