One year on from football abuse scandal being revealed, Derek Bell's memories can prevent this ever happening again

Former Newcastle midfielder felt he couldn't speak to anyone about the abuse he suffered 41 years ago, but now his story can help stop young footballers experiencing what he went through

Derek Bell rolls up the sleeves on his black hoody. Behind him a flatscreen is showing highlights of Birmingham against Aston Villa. In the booth beside us in a Tyneside bar are five women taking selfies and talking excitedly as they scan a drink’s menu.

“Can you take a picture of us please?” Bell is asked as a phone is passed in his direction.

He stands up and steadies the mobile. “Make sure you get us all in mind!” It is Friday afternoon and a pub is beginning to fill. The weekend is calling. A phone gets handed back and is inspected. “Very good!” comes a shriek, although one of the party is unsure.

Bell sits back down. “Anyway, if you look at my arms you can see the marks from where I was self-harming,” he says. “The scars are fading now, but you can still see them.”

Two booths, two different worlds.

“When did I stop? Oh, about a year ago.”

A year ago is when Derek Bell found the courage to tell his story, about the sexual abuse he suffered at the hands of a junior football coach in the north-east of England. We are sat in a bar in the shadow of the Gallowgate End of St James’ Park. Bell played for Newcastle United. He was abused by a coach who ended up at the club. He was sectioned and has somehow come through the other side.

His story is remarkable, in its sadness, its horror and incredibly, in its humour.

“Aye, some of it’s been like One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s nest,” he says. But he is smiling, and that is a huge start.

Derek Bell was 12 when he played for Montague and North Fenham.

“He groomed me at the boys club,” he adds. “He took me home and got into my house. He was 22 at the time. It was a rundown club in the West End of Newcastle. We’re going back to the 70s, cold showers and muddy boots. He used to take me into the treatment room. That’s how it started.

“He would be at our home and say his car couldn’t start. My mum and dad were completely unaware. They thought he was protecting me. He was allowed to stop over.

“At that time you couldn’t sign for a professional club until you were 14. I went on trial to Everton and Southampton. He said, ‘Sign for your home club’. I wanted to. It was only later I realised why. He wanted to keep control of me.

“I started training at Newcastle on a Thursday. He would be there. He would take me home. It was for years. We went to court in 2002. He was found guilty of 12 indecent assaults. Once he got into my home he did sexual acts on me.”

There is nothing to say when someone tells you that.

“My solace,” he says, “my freedom during those four years was when I played. I knew he couldn’t come onto the pitch. He couldn’t hurt me there. That was the only time I was safe; on a football pitch.”

Bell’s is a huge story to tell.

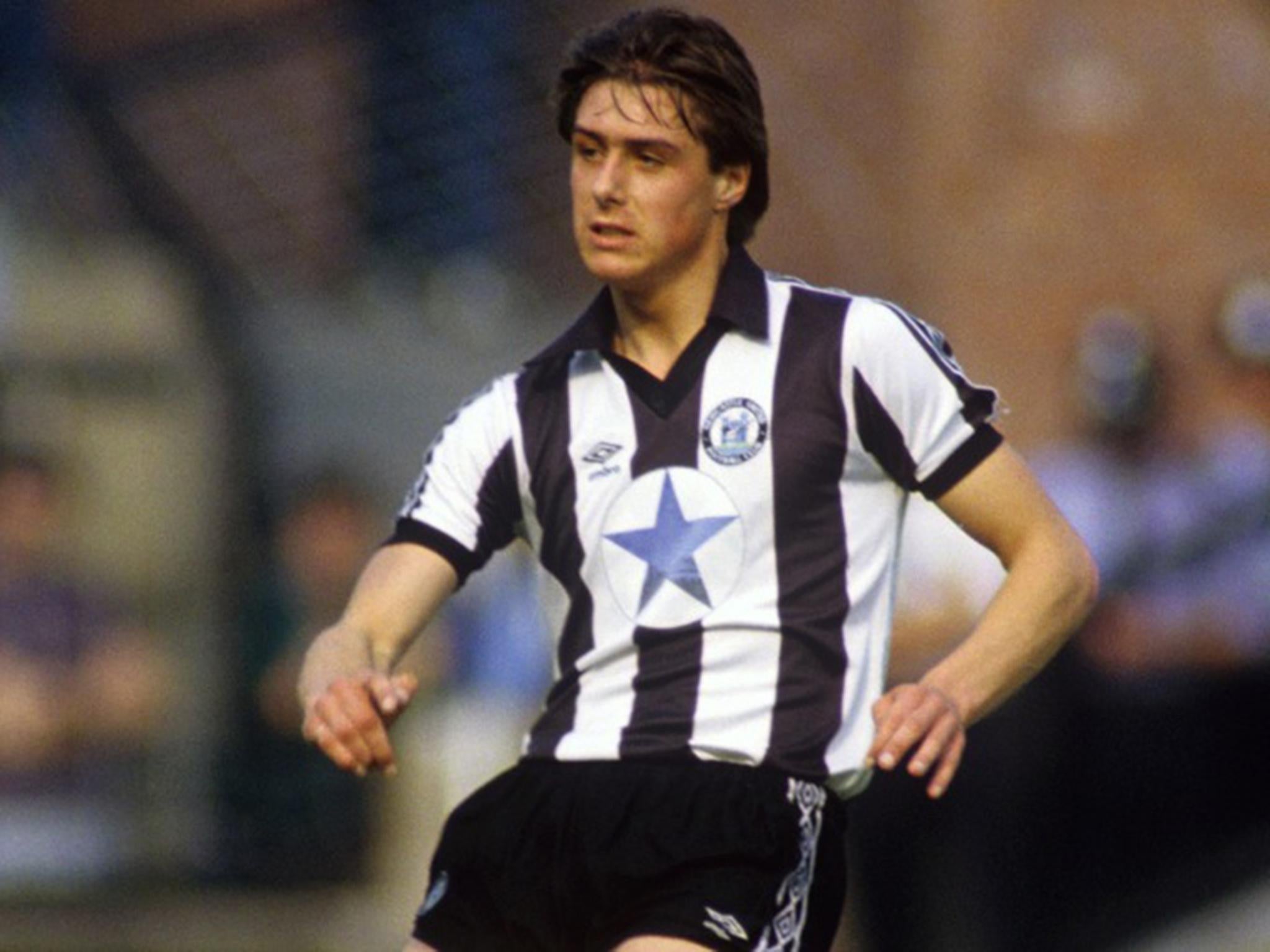

He recovered from an ankle problem to make his debut for Newcastle United, away to Blackburn Rovers in May, 1982. Newcastle lost 4-1. He started two more games for the club and then suffered a serious knee injury. He retired from professional football, at the age of 19. He played non-league in the north-east, chairmanned Gateshead FC, but a deep scar had darkened his soul.

He tried to kill himself three times. On one occasion, he came close to death.

“The ambulance came. I got put in the Leazes Wing of the RVI. I was locked up under the mental health act. I was sectioned for three months. A girl hanged herself along the corridor from me.

“One time we went in a room and there was a big screen. It was group therapy. They said, ‘Listen, there’s students behind the wall.’

“I said nothing for a week. This one day I just blew. I threw the chair and smashed the whole screen. The alarms went off, they were going ‘Derek what are you doing!?” I said ‘I’m sick of this.’

“They locked me up again for a few days to calm me down. I just felt the anger was going nowhere. I wasn't ready to speak then. It was too early.”

It was not all darkness.

“This guy had been in institutions all his life. In his 60s, big tall fella, he was the chief. Every day he would get his notepad out.

“Right, who’s going to Edinburgh Zoo today? Are you Derek? The bus is picking us up at ten o’clock. Are you Mary?

“I would say yes. Mary would say yes. He’d go, ‘Right, it’s £2 per person for the trip. I’ll get the money off you later.’

“So half past ten comes around, I’d say, ‘Geordie, where’s this bus?’ He’d go, ‘Aah, it’s broken down.’ He had an excuse every day. People believed him and they’d be going, “Geordie, I’m not happy the bus hasn’t turned up.’ There would be big rows about why we weren't going to Edinburgh Zoo to see the gorillas and the monkeys.

“I’m Mac Murphy. I can’t believe what I’m seeing. They'd go, ‘You played for Newcastle United! Aye righto, that’s why you're in here!’”

I wanted to hit him. When he left I was shaking. It’s like Pandora’s box. It had opened, everything opens again

He underwent treatment to deal with his anger. Later, there came a job with Newcastle City Council, housing asylum seekers. He was warned of BNP activists. Those he moved were vulnerable and were housed at night. In the darkness, hiding behind a tree, lurked a face from his past.

It was his abuser.

“I didn't know it was him,” he adds. “Then I saw who it was. I said, ‘What are you doing here?’ He went, ‘Oh these families shouldn't be here.’

“He knew who I was. Oh yeah, he nearly s*** himself when he seen me. I said ‘Get away from here now’. I wanted to hit him. When he left I was shaking. It’s like Pandora’s box. It had opened, everything opens again. For a few days I was thinking about it. I couldn’t sleep, but I couldn’t let it lie.”

Bell went to see him with a tape recorder and his abuser admitted his offences. “He went, ‘Yes, yes, I did them things, but you're not going to go to the police. You're not going to the police’. I was angry he hadn't said why, but I was relieved I had it on tape.”

That was in 2000. He went to the police. Two years later his abuser was found guilty of 12 counts of indecent assault on seven boys between 1975 and 1999. At that stage Bell retained his anonymity.

And then, on November 16, 2016, almost a year ago, Andy Woodward opened his heart publicly about the abuse he had suffered at the hands of a coach from when he was 11. Pandora’s box was open again, and Bell finally showed his demons to the world.

“I rang the NSPCC helpline that they put on the bottom of Andy’s story,” he says. “I said I’d been a victim and I’d been to court. Newcastle is my club, I wanted them to be warned and to support me. Lee Charnley (the managing director) was brilliant. He said, ‘Derek, whoever you need to speak to, we will help you’.

“When I came out in support of the victims, I got a call from Gordon Taylor. He said, ‘We’ve a lot of things going forward. Would you mind meeting up and having a chat because your case is finished?’

I couldn’t have sat here a year ago and had this conversation with you

“Greg Clarke rang up, he said ‘I’d like to invite you, Paul Stewart, Ian Ackley and David White down to Wembley because we as a public body have to look at this as a serious thing. I asked what help they had and he went, ‘None. I will admit to you that we've got no provisions to deal with this.’ That was December.

“I said to Simon Bailey from the police, ‘What have you got?’ He said, ‘We haven't got anything.’ The PFA said, ‘We’ve got Sporting Chance.’ I said, ‘Nah, you've only got six beds.’

“All your leading governing bodies didn't know how to cope with it.”

Astonishingly, 741 victims have come forward.

“Greg Clarke asked us to work around safeguarding and we are holding him to task on this. It has been ongoing with SAVE.”

The black sleeves are rolled down when we finish, those scars are fading and there is a sense of purpose to Bell that perhaps has not been there since he was first abused as a 12-year-old.

“I couldn’t have sat here a year ago and had this conversation with you,” he says. “The whole thing is about ensuring what happened to me doesn't happen to someone else.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.