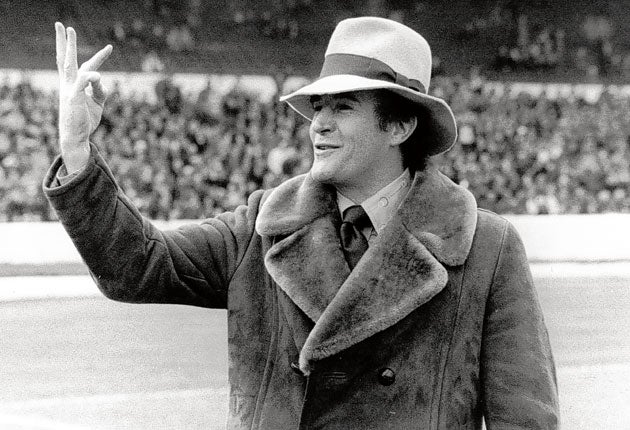

Hats off to Big Mal, the visionary coach who was ahead of the game

Flamboyant figure who lit up the blue half of Manchester had a gift for inspiring players

The best of Big Mal some time ago drifted off into a half-world that was the most poignant mockery of all the wit and vibrancy and sheer, madcap courage that made him the most brilliant football coach of his times.

Even now, though, when the assault of his last years is over, there is one great certainty for all those who admired and loved him.

It is that few men, in or out of the boundaries of the game he made so thrilling, will ever be more easily conjured.

Bobby Moore's devotion was as strong on the day he died as when, as a young contender at West Ham who one day would take his place in the team and surpass every football dream of a young Englishman, he trailed after him like a faithful spaniel, weighing every word – and laughing at every joke. "Malcolm saw something in me that others didn't. Yes, I loved him," said Moore.

Not all aspects of Malcolm Allison were admirable, he was always the first to admit. Family life was an anarchic nightmare for the women who cared for him and bore his children and for every pound he earned at the pinnacle of his career in the late Sixties and early Seventies he spent at least two.

He wore the constraints of normal life like a tight-fitting coat bursting at the seams but for some years at least, before the disappointment that came with his failure to extend the luminous creativity of his coaching career into more than fleeting success as a manager, there was a pulsating redemption.

It was his ability to animate almost every footballer who came into his care, and one of the most successful of them, Mike Summerbee, yesterday, spoke for all those touched by the force of his understanding of what a professional footballer needed in order to give of his best.

"Malcolm Allison was years ahead of his time," said Summerbee. That is true enough but it was only part of the genius. It seemed that his talent not only carried him into the future but also the past; his head, which remained almost ridiculously handsome deep into old age, was a storehouse of lessons from yesterday and the most exciting possibilities for tomorrow.

Now, when the campaign for a native-born coach of the England team is at full bore despite the absence of the ghost of a credible candidate, it is more than ever inconceivable that he was never recognised as a serious candidate by the Football Association.

The FA's reservation, though, was almost entirely to do with the resentment caused by Allison's near total failure to conceal his contempt for so much of the football establishment. Serially, he fell foul of the FA's disciplinary committee – and nor did he earn much applause from some of his fiercest rivals. Bill Shankly once declared that Allison was mad, clinically. Don Revie of Leeds United said that he was a "disgrace to the game", and Sir Matt Busby was severely miffed when the new man in town said that Manchester United's easy superiority was about to go up in blue smoke.

But no one could question the quality of the football Allison made – or his ability to go to the heart of the sport's deepest problems. In the early Seventies he announced that Fifa had to face up to a deepening malaise in the way the game was being played.

Fifa had to banish the back-pass directly to the goalkeeper. It had become the prop of lazy, cowardly defenders and coaches. Games were being destroyed by the formula of passing back to the keeper at the first hint of pressure – and then having the ball hoofed downfield. Derision greeted Allison's call. It was nearly 20 years later when the world authority, appalled by the football of the World Cup of Italy in 1990 and facing the prospect of selling the game in America four years later, finally acted on Allison's proposal.

Of course Allison will hardly be remembered for such tactical prescience or his understanding that modern science had to be applied. No, the unbreakable image is of the fedora and the panache and the bunny girls and the outrage piled upon outrage, not least when he posed in the Selhurst Park baths with the soft porn star Fiona Richmond. Such shocking memories may be inevitable, but they should never be mistaken for the whole and essential story.

The great football man Joe Mercer, who had suffered a nervous breakdown while manager of Aston Villa, reached for the phone to call Allison in his first official act as the new manager of Second Division Manchester City. Later, their relationship foundered on Allison's ambition to manage the club but for a few years it constituted football heaven, a mature voice from the highest level of the game, softening the impact of a brilliant but turbulent young football man.

Allison never made any secret of his driving force as a coach. He saw himself as a failed player, first with Charlton Athletic, then West Ham (despite more than 200 appearances) and he wept with grief when young Moore was selected ahead of him – and there came the hammer blow of tuberculosis and the removal of a lung.

He was lost for a little while, partnering his friend and former Arsenal full-back Arthur Shaw as a professional gambler for two years and running a drinking club in Soho's Tin Pan Alley. But then his vision of how football should be played, how English football had to break out of a stranglehold of stale tradition, was never quite lost.

His passion for innovation was born in 1948, when as a national serviceman in Vienna, he slipped into the Soviet zone and watched the Red Army team training in the Prater woods. "The Russians were training in big army boots," he reported, "but they had a lovely touch and they worked with the ball so much; it was a revelation and when I returned to Charlton I told the manager Jimmy Seed that what we were doing was just crap."

When he went to coach at Cambridge University his urge to teach football was reignited and his progress was meteoric: Bath City, Plymouth Argyle, and then the call from Mercer. The rise of City is one of the landmarks of England football history. It was brief but stunning: promotion to the First Division, the title two years later, then the FA Cup, and, at the end of a three-year cycle, the League Cup and the Cup-Winners' Cup.

He returned to Vienna for that triumph, a superb performance against the then formidable Polish team Gornik Zabrze. Rain streamed down his face as he sat beside Mercer in the Prater Stadium but he was the picture of exhilaration and on the balcony of his hotel room he greeted the dawn with a glass of champagne, a fine Havana cigar and the declaration, "This morning I feel like Napoleon."

This was two years after his personal Waterloo – ejection from the first round of the European Cup in Istanbul. After winning the First Division in a brilliant finish, Allison, always a newspaperman's delight, announced, "Next stop Mars."

He had sounder prospects in Turin, where Umberto Agnelli, head of Fiat and president of Juventus, offered him a then princely £20,000 a year – and a chartered plane to fly in his friends from England after every home match. The offer survived newspaper pictures of Allison walking a nightclub dancer – and her poodle – in the Italian dawn.

Later, he confided, "I've often wondered what would have happened if I'd gone to Italy, but I also know that I loved my City team, it was so hard to break away."

He stayed and was, largely invaded by anti-climax. You saw him in outposts like Istanbul and Setubal in later years, after the erosion of City's glory, the miscalculated signing of Rodney Marsh and the parting with Mercer and you wondered how such strength and charisma and talent could drain away.

Of course there were moments, the defeat of Leeds United in the FA Cup in partnership with Terry Venables at Crystal Palace on the way to a semi-final, a snatched Portuguese title with Sporting Lisbon, and when you saw him, in a dugout in Brussels or Lisbon or a nightclub in London or Barcelona, there was, until he finally gave up while in charge of Bristol Rovers in the early 1990s, always a resolution that the good days would come again.

Good days – and good nights. Like the one in Coimbra in Portugal scouting a coming tie for City and getting joyously drunk when things were still good between him and Mercer, and Allison explaining to the older man that when you are laying on your bed in a room spinning around your head, there is an easy solution. You simply put one foot on the floor.

It was sound but ironic advice from a huge man who, for all his gifts, could never quite master that particular art.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies