James Lawton: Capello must turn last street footballer from dying breed to first among equals

Forget the overcooked ceremonials of David Beckham's "long goodbye" and his nightmare assumption that he is some permanent fixture in a team that still screams for new purpose and harder values and, not least, the speed he hasn't lost but never had. The most truly poignant moment at the Stade de France this week concerned something we can only hope is a briefly clouded future rather than an overstated past.

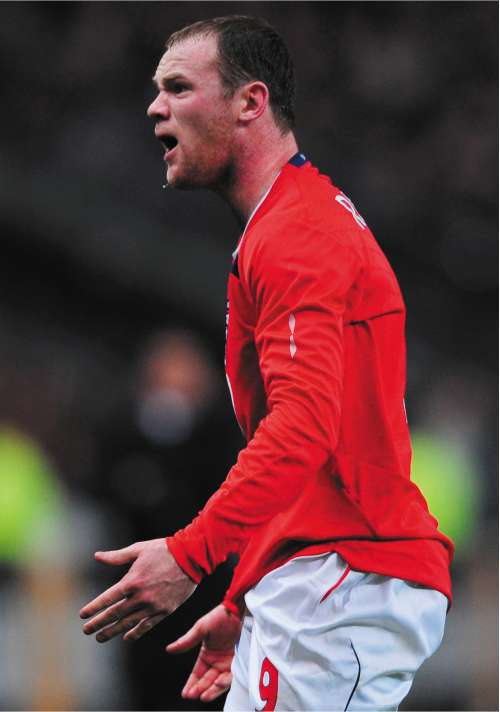

It was the sight of Wayne Rooney dropping deep, rather like a stranger at a party looking for an intelligent conversation, and creating a rare flash of English coherence and bite. Nothing of significance ensued, all night long, and nor will it, you have to suspect, until Fabio Capello is able to push beyond his necessarily basic credo of passing and running and the creation of some consistent shape and rhythm.

The first priority, and the need for its imposition was surely underlined by the dynamism and unceasing relevance of France's best player, Franck Ribéry, is to get something more out of Rooney. He is currently a national treasure gathering dust.

Capello knows better than anyone the need is not for revaluation but effective realignment of resources so scant that at times on Wednesday the shortfall was simply embarrassing. In his first official chore, the manager watched Rooney engulf one of the better Premier League teams, Aston Villa, in a 20-minute substitution stint.

Rooney was immense – but in his two games for Capello he has been near to anonymous.

The problem is that playing him alone up front, without the diversionary brilliance of his Old Trafford team-mate Cristiano Ronaldo or the support of the burrowing Carlos Tevez, is not so much a strategy as a confession. It is saying that for the moment England have a need in attack so critical that the sheer talent of Rooney offers the best chance of some return.

It can't go on, not in the interests of anyone, and least of all Rooney, and if there is any encouragement this morning it is that Capello didn't win all his Scudettos and his Champions League title by sitting on his hands. He has already noted the speed and effective simplicity of Aston Villa's Gabriel Agbonlahor, and these qualities may have grown even larger after the failure of Michael Owen and Peter Crouch to announce themselves as a dream partnership in the second half.

Capello asks for patience – and who could deny him after making the most cursory trawl back through the years of English decline? The manager insisted he saw a few green shoots at the Stade de France, a little more understanding about the need to hold the ball, but if there was some progress not immediately obvious to the naked eye, unfortunately it was dwarfed the moment the French elected to storm into a canter. That, certainly, was the effect when Ribéry, Nicolas Anelka and, on occasions, Florent Malouda, lifted their heels.

When English creativity was at its lowest point Rooney's plight seemed like the last indictment of the national football culture. The other day he was described as "the last of the street footballers" and for some it was a phrase that resonated rather more powerfully than the stagy exit of a Beckham who had brought so little with him on the flight from California – and who, symbolically enough, was booked for tugging at the shirt of Ribery, a player of the moment and the future.

You could only yearn for the Rooney who brought such thrilling impact to the England team when he electrified their European Championship qualifying campaign for 2004, and then threatened to take them all the way before being cut down by the most cruelly timed injury in Portugal.

Capello's challenge is surely to reanimate the street footballer in the cause of England.

On Wednesday night we saw the charge that one player can bring to a team when he is clearly on top of his game and at a peak of confidence. At times Ribéry was incandescent. Rooney, but for that brief burst of skill and intuition, gnawed on his frustration. So, no doubt, did Capello.

However, these remain the earliest of days, and it has to be remembered that the one England manager to win the World Cup made a much less auspicious start than Capello, with his victory and defeat against Switzerland and France, and, for that perspective-yielding matter, Steve McClaren, whose "revolution" started with a dismembering of a Greek team so passive they stopped short only at taking a collective nap.

Alf Ramsey's first England team had five goals put past them – by France. But then Ramsey made a team. McClaren floundered against Macedonia and had difficulties with Andorra. Capello was able to make the point that his players had been exposed to a front-rank team which might well have won the World Cup but for the brainstorm of Zinedine Zidane.

The result at times suggested not so much a wake-up call as a collapse of the bed. Certainly, players like Steven Gerrard and the indisposed Frank Lampard had reason to reassess their England prospects.

Gerrard had the vital role of bringing Rooney into the action in optimum circumstances, but we didn't see much of that. Instead, there were a few clashing of cymbals and the odd puff of smoke, but nothing of substance to dazzle a man who once had at his disposal players like Ruud Gullit, Marco van Basten and Franco Baresi.

We can only guess quite how much he yearned for such dominating quality when Ribéry and Anelka were running where they pleased.

Still, he does have the street kid, a world-class asset – if only he can find his right place in the international market.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments