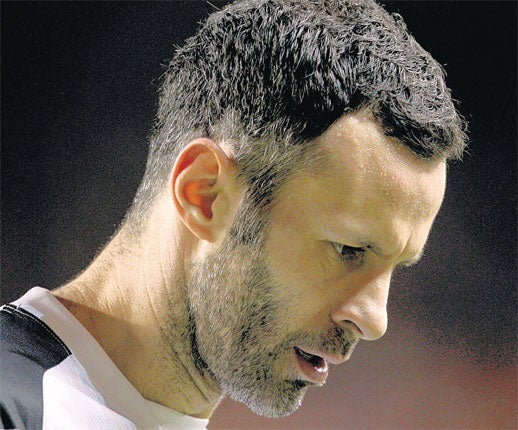

James Lawton: Faithful will forgive Giggs for his infidelity if he shows best of himself at Wembley

How long did the worst that came to Rooney when he fell victim to kiss and tell last among his biggest fans? Only until he proved again the best of his talent

Flushed out of his cover like some hunted game by maybe the most prurient version of Tally Ho in the history of celebrity culture, Ryan Giggs must now proceed with the rest of his life.

We can only hope that in a few days time he can seize the opportunity to re-define himself at Wembley Stadium doing something he has always done best, something that will carry him far away from the banalities of a Twitter feeding frenzy and the consequences of the sexual indiscretion he tried to bury in the routine way of so many of his rich contemporaries.

It is not a pious hope because if his injunction failed, if he was unsuccessful in the way of Tiger Woods in an attempt to live, however briefly, one life and while presenting the carefully tailored clothes of another one, it is still true that as in the cases of so many 24-carat heroes before him at least some of us are still ready to respond to the best of him and live with the rest.

If Giggs can be at all faithful to the meaning of his extraordinary career against the brilliant Barcelona team in the Champions League final on Saturday – assuming his Manchester United manager Sir Alex Ferguson believes the last few days have not drained him too deeply – he can be sure that the reaction will be overwhelming positive.

He might even be able to draw a new, grown-up line between the public deeds of a man of brilliant accomplishment, someone who has never given less than was within his extraordinary powers on every public appearance, and those which he has assigned more recklessly to the bedroom.

We do not know the considerations that drew Giggs to the injunction solution that had, day-by-day, been so relentlessly undermined by the Twitter culture that invites so much of humanity to prove its existence three or four times in no more than 140 characters.

Many claims are made on its behalf by the Tweeters, including the inspiration for the Arab Spring and some even see a bonus in the flow of profound insights from such as Piers Morgan and Wayne Rooney.

But do not tell any of this to Ryan Giggs, who sought to cover up his mistake without imagining that his dalliance with a "star" of reality television would be twittered into the furthest reaches of distant valleys where maybe before goatherds had only to listen to the tinkling of bells and the moaning of the wind.

It may be asking too much for Giggs to absorb the ludicrousness of his situation and grasp, even as Lionel Messi and Andre Iniesta and Xavi Hernandez finetune their most devastating routines, that long after the hysteria surrounding his exposure is forgotten he will be remembered most surely for what he achieved doing the thing that he was born to do.

How long did the worst of the infamy that came to Wayne Rooney when he fell victim to kiss and tell last among his most ardent followers? Only until he proved again that the crisis to his marriage, and the waves of scorn from hostile terraces, had not separated him from some of the best of his talent. Will the Tiger be a figure of scorn if he again reclaims the genius that was his companion for so many years? Indeed, he was reassured about this by a crowd composed largely of Giggs' compatriots in a Welsh valley before the start of the Ryder Cup last autumn.

There were great cheers for the European heroes but nothing matched the roar that came when Woods was introduced to the crowd. There were not cheering a serial Lothario.

They were saluting a man who had brought unmatched excitement with his ability to produce all of his gifts when it mattered most.

Giggs, if he cares to think about it for a moment, can draw from a similar legacy of respect if and when he goes out at Wembley for one of the most important games of his career, a match which before the Twitter onslaught presented itself as the most uncomplicated, and climactic, of his career challenges.

He can think of his great predecessor George Best, who said dryly when being taken down to the cells after a brief lifetime of misadventure had led to a conviction for drink driving, "there goes the knighthood."

But Best was redeemed a thousand times in the memory of all those who had been thrilled by the glory of his football. Giggs isn't Best and now he is no longer a paragon of all the virtues but he should know that it will take more than some risk-filled forays into the night to permanently besmirch the meaning of what he has achieved. Doubtless, though, he was aware of the radically changed nature of his existence, and an image that in recent years has at times been close to deification, long before an MP yesterday named him in the House of Commons. Rightly or wrongly, John Hemming claimed that he was serving reality and moving to end the absurdity of the worst kept secret in British public life. Certainly he was making a test case, ironically, of a football player who right from the start had been zealously protected from the glare of publicity.

Ferguson railed against anyone who mentioned his name in the same breath as Best's. He screened him from interviews in the first rush of his fame. He fussed over his privacy, warned him against the perils that lurked beyond Old Trafford. As the years passed, Giggs seemed to be an extraordinary example of a leading professional sportsman who had learned to live a high-profile life without the destructive, attendant perils.

Best and Paul Gascoigne and lesser talents ran to the limelight and were impaled for their rashness. Giggs' progress was serene; if he erred, he had a brilliant system of damage control. He became what he was perceived to be: an outstanding professional who accepted that for quite some time he had to impose his own discipline, his own understanding of what he was always required to do – and not do.

The last and potentially crushing irony is that his carefully constructed world should unravel in this week of all weeks. He does however have one powerful trick left at his disposal. He can still play the game for which he was born. He can remind the world of what can still bring him to Wembley Stadium for what could prove the biggest match of his life. He may yet walk, unmolested, through a million tweets.

Major flaw puts English triumphalism in perspective

No doubt it is a matter of much pride that Ian Poulter's weekend victory was the fourth straight English triumph in a match-play tournament.

Strong bragging rights indeed, and especially with the beaten Luke Donald frustrated in his attempt to supplant Lee Westwood at the top of the world rankings. Yet there is still a need to hold any announcement of the golden age of English golf.

This, at least, is a caution that must be supported by all those who think that any measurement of golfing greatness will always be best applied to the challenge presented by the major tournaments. Here, the English glory is somewhat muted.

Of the past 73 majors, two have been won by one Englishman, Sir Nick Faldo, who triumphed in the 1992 Open and the 1996 Masters. This leaves England trailing South Africa (8), Ireland, Australia and Fiji (3), tying with Germany, Spain and Argentina, and one ahead of South Korea, Northern Ireland, New Zealand and Canada.

In the same period the Americans have won a total of 40 majors. While it is true they have the largest golf population in the world, we maybe ought to also remember that England has a rather huge edge on Fiji. It might just keep certain perspectives up to par.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments