Why being brilliant at sport is still no bar to depression - Michael Calvin

THE LAST WORD: Britain’s Tasha Danvers says admitting to a problem is seen as admitting to a weakness

The football manager retreats to his study at home. He drains two bottles of red wine, broods over a video of that day’s match and wilfully isolates himself from those he loves. His marriage is, to all intents and purposes, over because of his mood swings.

The Premier League player, struggling to sustain the dream which made him a teenaged millionaire, hates the game which has enriched him beyond reason. Pressured by an extended family which views him as a meal ticket, he is, according to his manager, becoming impossible to select.

The golfer, alone in yet another featureless hotel room, weeps. His excellence on the course is automatic, almost unthinking, but he is perversely petrified of losing control on the practice range. He refuses to believe his supposed long-term back problem is psychosomatic.

Those three case studies must be anonymised, because of the delicacy of their situation. You will know their names and achievements, but unless and until they waive their right to privacy their struggle must be shared only by those closest to them.

Saturday was World Mental Health Day. The national launch of the new Mental Health Charter for Sport and Recreation will take place at half-time in the televised League Two match between Exeter City and Stevenage.

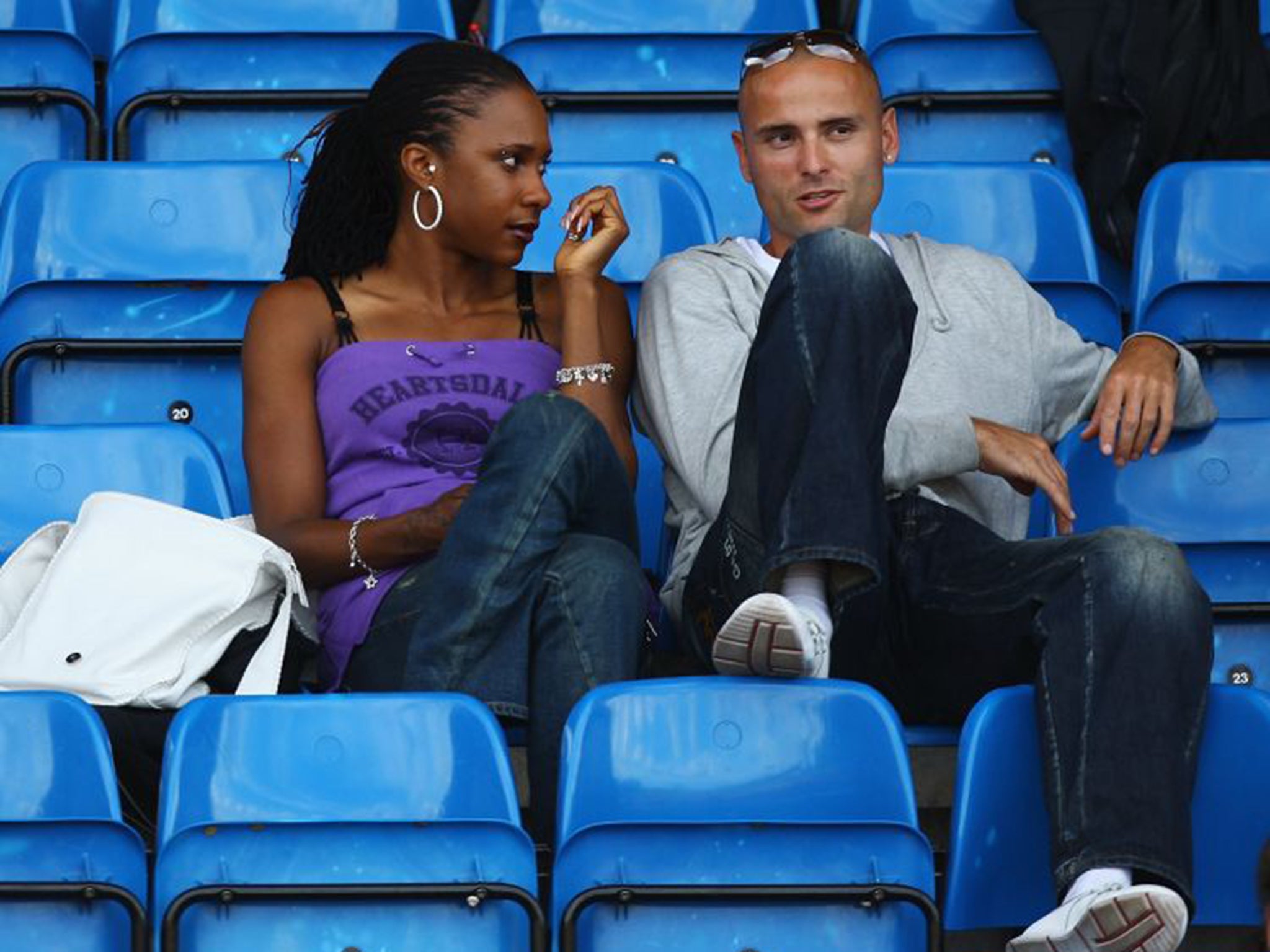

Depression ignores an athlete’s age and class, sport and sex. It is an insidious disease, since it uses the self- reliance deemed central to the psyche of a successful sportsman or woman. The contradiction is exposed by hurdler Natasha Danvers (above, left), a bronze medallist at the Beijing Olympics.

“I’ve grown up in my sport with the impression I was meant to be a superhero,” she says in an awareness campaign undertaken by Mind, the mental-health charity. “You’re supposed to be able to handle things. You are in high-pressure situations so it is hard to get help. It is admitting you have a weakness.”

There is nothing weak about those who articulate their fears and failures. Martin Ling, the former Leyton Orient, Torquay and Cambridge manager, showed immense moral courage in recalling his depressive episode, since he was acutely aware of the danger of stigmatisation.

He refers to it as “a coffee stain on my CV” but has quietly become an inspirational figure to those experiencing similar problems. He shares his story in a holistic support programme overseen by the League Managers Association, and has been approached by the FA to contribute to coach education. His avowed hope is “this shows we are not two-headed monsters”.

The focus on football is, for once, positive, due to the platform it provides other eloquent victims. Clarke Carlisle, recovering from a second suicide attempt, has been admirably open about the danger signs of stress, such as the timbre of his voice and the tone of his social-media messages.

A new survey of more than 800 footballers across 11 countries sketched the parameters of the problem: 38 per cent of current players and 35 per cent of former players reported symptoms of anxiety and depression. A quarter struggled to sleep, alcohol abuse was rife, and those who suffered serious injury were nearly four times more likely to have mental-health issues.

Success and celebrity offer no refuge. The complexities of Freddie Flintoff’s character, highlighted this weekend by the serialisation of his second autobiography, made the combination of alcohol, exhibitionism and self-doubt uniquely toxic.

Dual Olympic champion Dame Kelly Holmes overcame clinical depression, which involved an ominously typical episode of self-harm. She locked herself in a bathroom and cut her left arm with a scissors’ blade; each incision represented every day she had been injured.

Her experience informs her belief that depression is triggered by the difficulty in retaining an emotional balance in elite sport, where the highs are stratospheric and the lows subterranean. Her message is identical to that of Stan Collymore, the footballer who has become a pungent commentator:

“Encourage someone to talk. It may change their life for the better.”

Thanks Tonga, now leave

The final whistle sounded at precisely 9.55pm on Friday night. A capacity crowd at St James’ Park rose to salute the spirit of Ikale Tahi, the Tongan national rugby team, in losing to the All Blacks. By 6am Saturday, they had checked out of their hotel to return home, carried away with the rubbish in a manner which highlights the shameful inequalities of this World Cup.

The Tongans were everything an impeccably-run tournament was supposed to represent, from the muscular intensity of their rugby to their pride in the Sipi Tau, their tribal response to the haka.

Yet rules, it seems, are rules. The organisers of an event likely to generate in the region of £120m will only pay for return air or train tickets if they are taken 24 hours after their final fixture.

Such inflexibility forces injured players to fly, and means amateur players must fend for themselves if they wish to linger, to experience a competition they have enriched.

There is no time to savour a career-affirming experience. The Georgia team were shipped home 24 hours before Tonga’s defeat in Newcastle confirmed their automatic qualification for the 2019 World Cup.

Tier Two countries, who receive £150,000 in compensation fees compared to the £7m guaranteed to elite nations, also have justifiable complaints about an unbalanced disciplinary process. They deserve better than to be patronised and pushed to the margins with indecent haste.

Jose’s Klopp challenge

Jose Mourinho’s travails at Chelsea have attracted less than universal sympathy. His ego has been shredded and his reputation suddenly seems rather shop soiled.

Perpetually irked by the respect afforded Arsène Wenger, a considerably more cerebral manager, Mourinho has now to deal with the man love which has swamped Jurgen Klopp. It may just drive him over the edge into self-parody.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks