Steve Bunce on Boxing: Frank Maloney, the duck-and-dive prince, will be missed from Battersea to New York

He decided to walk away from the sport last week after 40 years of involvement at every possible level and he left behind two British champions and a handful of young fighters

If you have ever spent five minutes in the essayist Damon Runyon's company wandering the dives, gyms and flops that kept the business of boxing booming in a golden age that was not that clever, then you will understand the shortage of characters in the modern business.

There was once an oasis for lunatics in south London on the Old Kent Road, where two rival pubs, The Henry Cooper and the Thomas A'Beckett, formed the backbone of British boxing for a few decades. Men came and went and watched Muhammad Ali, Sugar Ray Robinson, Marvin Hagler and thousands of other fighters skip and slip across the stained floors.

I first walked through the Beckett doors as a kid of 12 hoping to catch a glimpse of John Conteh, but my information was dud and I watched a selection of forgotten local heroes like Johnny Clark, Ray Fallone and men for hire as sparring partners like Panther Cyril. The Beckett was virtually on its own as the last remaining solid professional boxing gym in London by about 1980.

The ring was shrouded in smoke and men in suits did watch the sparring in silence with a light ale in their hand. In the ring young fighters desperate to impress traded vicious punches hoping that their flair would be noticed and the spotters would report back to the sport's big men. It was Runyon time just off the Elephant and Castle and the gyms were a last retreat for spivs.

The men with the light ales were genuinely called The Dog, The Scarf and The Growler and they all had real jobs either driving a taxi, selling The Standard or holding up armoured cars. A word from the wise was the difference between turning professional with Paddy Byrne and no television, or turning with Terry Lawless and possibly getting television; the sparring was a meat market sale and rivalry fierce. A spear was once thrown at and remained in the door at the Cooper after a dispute.

Frank Maloney was part of that world and came to be the Guv'nor of the outposts, even as one pub closed and the other faded and eventually shut its doors for good. Maloney was a local boy, a young amateur boxer who then started to look after a boxing club called Trinity ABC, where he was the competition secretary, which means he was the matchmaker. The Beckett and the Cooper became his living rooms.

Maloney decided to walk away from the sport last week after 40 years of involvement at every possible level and he left behind two British champions and a handful of young fighters. Two weeks ago, at the funeral of Maloney's friend and highly regarded manager, trainer and matchmaker Dean Powell, it was clear that little Frank had fallen out of love with the sport. "I walk in a gym and I don't get the buzz. It's not the same," he said.

Maloney started off at the lowest level, grubbing a living from small shows and signing up fighters that he liked, most of whom would struggle to become champion of Peckham or the second-best lightweight in Lambeth. He trained fighters, he matched fighters, he managed, he promoted and all the time he was in and out of the boxing pubs. He often had his enigmatic brother Eugene at his side; a figure of considerable menace at times, who often vanishes for years and surfaces as keen as ever to gamble at ringside.

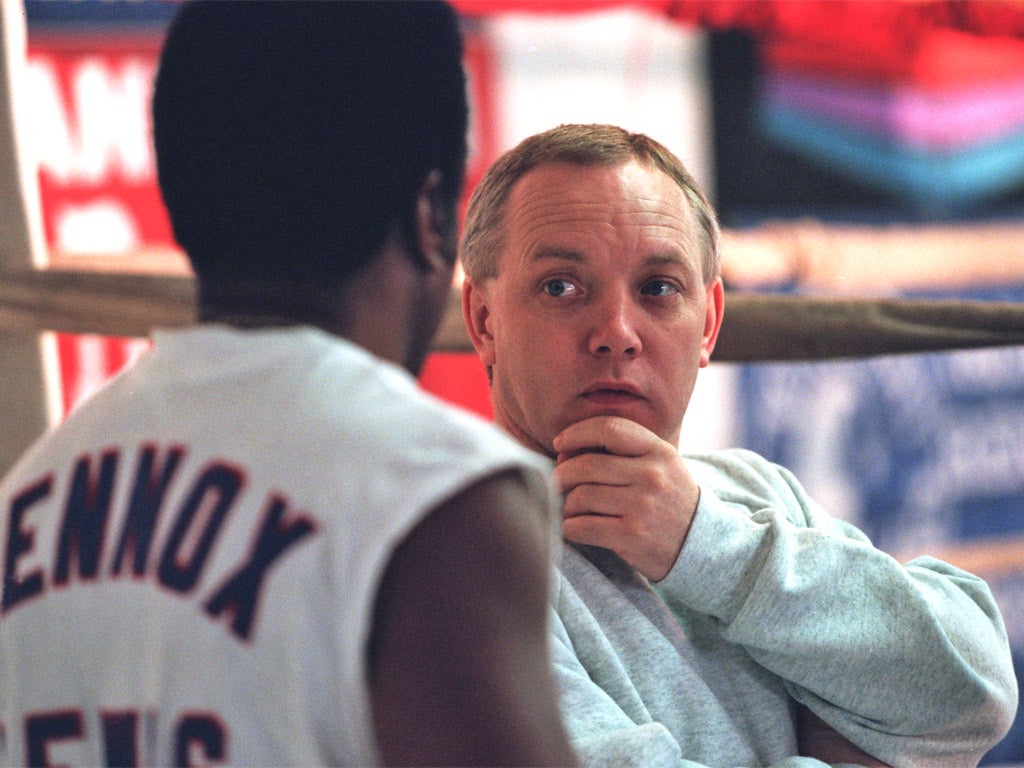

In 1988 Maloney took a call from a photographer he knew who was at a fight in Atlantic City, and it led to him becoming the manager of Seoul gold medal winner Lennox Lewis, who was struggling to get a deal in America. Maloney, the Beckett urchin and duck-and-dive prince, was transformed and took every one of the proper boxing media on a magnificent journey that lasted about 15 years.

In 1993 he was dubbed The Mental Midget by Don King's PR man, Mike Marley, and the same man has called for Maloney's trademark Union flag suit to now be given a place at the Boxing Hall of Fame in New York. "I love little Frank, he is a real boxing man," said King.

Maloney ended his days in boxing with current British heavyweight champion David Price still on his books, and apparently big Pricey was shocked when Maloney told him he was walking away. Maloney loved a heavyweight and promoted Nikolai Valuev, who would become "The Beast from the East" and world champion, at Battersea Town Hall and also Sugar Raj Kumah, a Delhi policeman, who was terrible and quickly packed off back to India. "I got out of the Valuev business a bit sharpish because every week more big, mean-looking Russians would tell me that they owned him," said Maloney. "I never called him Sugar Raj, that was you," Maloney reminded me when I reminded him of Sugar's York Hall debut.

Maloney will be missed and with the early death of Powell, who moved to London from Dudley in 1988 and lived on the floor at the Beckett, the sport has lost two men that could have wandered up and down any boxing Broadway next to Runyon's Harry the Horse, Sorrowful or Frankie Ferocious. They will both be missed.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies