The Last Word: It is ludicrous to say sport and politics should never mix... they have no choice

Sport does not take place in a social vacuum. It will admit many poisons

Even their most savage desecration can ultimately renew our best values and aspirations. In Boston on Monday, the first instinct of many was actually to run towards the blast. From that moment countless miniature kindnesses – like a bank of pebbles, piled by the waves of a storm – gradually stemmed the highest tide of hatred.

And so we "engage" with our enemy: his craziness, his cowardice, ultimately draws its negation in compassion and courage. In blatantly targeting an event that celebrates human endurance, he sought to maximise our sense of violation and vulnerability. As such, all of us who love sport, in particular, should consider what we mean when we vow vigilance on behalf of its purity and ethics.

He chose as his victims these symbols of unadorned endeavour. But to describe a marathon runner as the epitome of sport's essential innocence is itself a social observation. For it is no good pretending that the turf between painted white lines provides some prelapsarian Eden.

As a rule, admittedly, this kind of outrage will be perpetrated beyond the garden perimeter. But we should never simply prop a ladder against the wall, peer at the pall of smoke and shake our heads. "Wow, those guys out there…" we say. "They must be nuts. Anyway, on with the show…"

If sport is to mean anything, it can have no walls. Because you can bet they will typically be built only to secure commercial gain for those who put on a spectacle in two dimensions, as a sanitised, modern equivalent of bread and circuses. And, before you know it, you end up staging a grand prix somewhere like Bahrain.

The professional crises of a sportsman occur in a trivial, contrived environment. But we can nonetheless recognise the character he shows as authentic – and even as legitimately inspiring, for the daily challenges of "real" life. So when the toxicity of the world beyond intrudes shockingly upon the sporting garden, we have to see that logic through.

Sport does not take place in a social vacuum. It will admit poisons of many different flavours and intensities. What happened in Boston was at the most terrifying limit of the spectrum. But over the past week we have also seen cricket revisit its corruption trauma, and a vile regression in English football fans.

If sport, on and off the field, serves as a microcosm of social challenges and behaviour, then it can only profess innocence by refusing guilt. And that's why it's ludicrous to say that sport and politics should never mix. They have no choice.

For while sport can sometimes find itself helpless, against violence or madness or injustice, then it can also help to light a path.

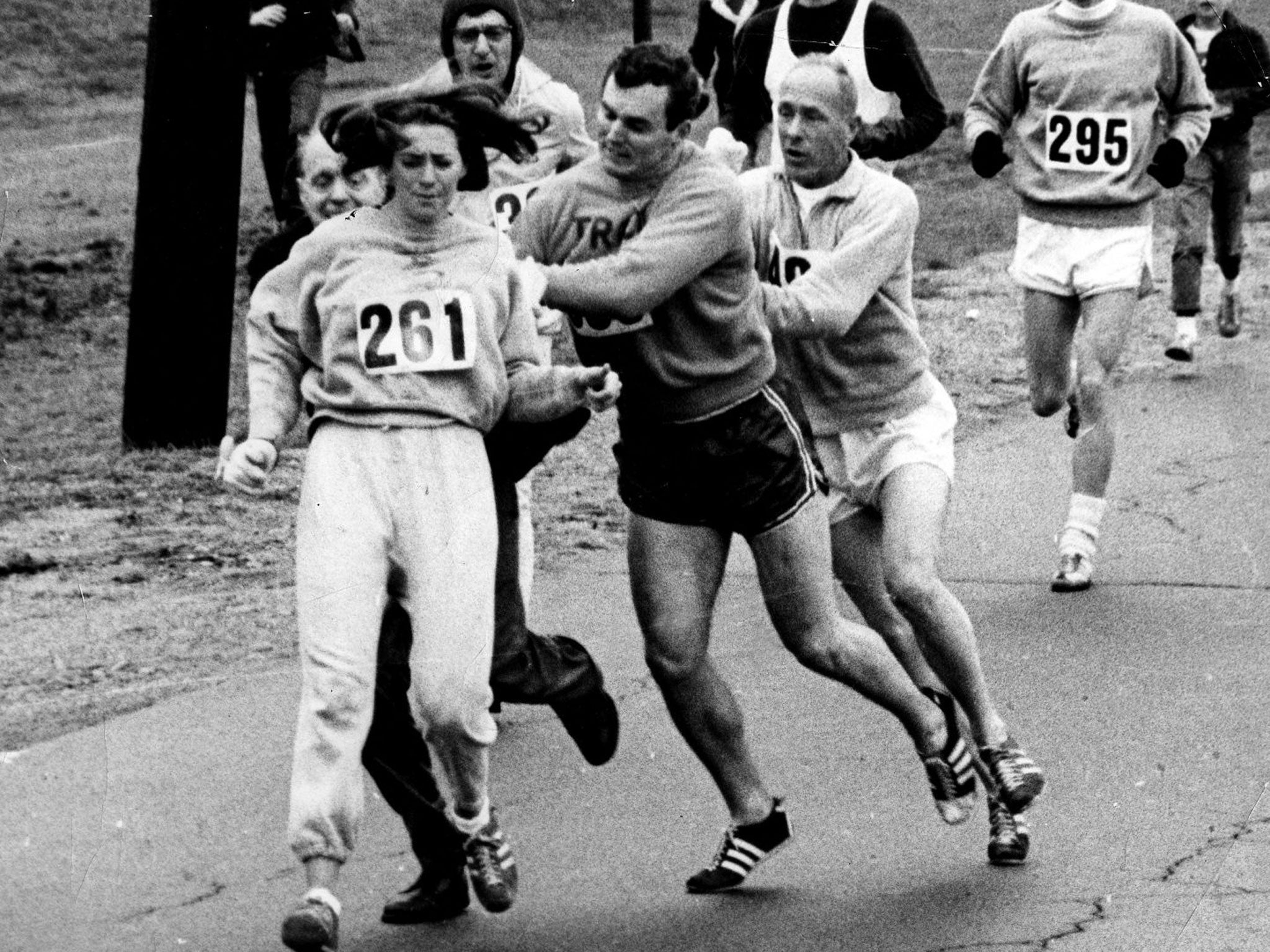

This, remember, is not the first time the Boston Marathon has breached the walls that might otherwise divide it from a more complex world. In 1967, K V Switzer registered for the historic, all-male race. After five miles, one of the organisers – having realised that K stood for Kathrine – leapt off a truck yelling: "Get the hell out of my race!" He ran towards Switzer, his face full of venom, to pull off her bib and barge her out of the field. But in his final step before impact, he was himself shouldered away by the men running with her. The moment was captured by global headlines and moving images that found a place in Time magazine's "100 Photos That Changed The World". Switzer never intended a political statement, as such. She just wanted to run the Boston Marathon. But an individual's innocent ambition was defined by the political and social guilt of others. And she duly opened the door to millions of female runners since, all round the world. The incident had frightened and embarrassed her, but with every step thereafter she found new determination, strength, meaning.

Remember, also, as you watch Formula One buttress a regime guilty of harrowing oppression, something else that happened in Boston on Monday – at Fenway Park, as at every other baseball ground on Jackie Robinson Day. Every player wore the number 42, to honour the man who broke his sport's colour bar in 1947.

A film celebrating Robinson's historic impetus to the Civil Rights movement has just been released in America. Let's hope it crosses the ocean soon. For his story is not about racial barriers alone. It is about human dignity, and so transcends all national and cultural frontiers – never mind the boundaries of a stadium.

In sport, as in every other walk of life, society often owes its progress to the bravery of individuals like Robinson and Switzer. Whenever it confronts evil, then, let sport collectively honour that debt – and do so with a suitable sense of its place in the world.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks