Six Nations 2019: A tournament big enough to stand out from the rest steeped in history and conflict

The weapons may have changed over the years but the feeling remains the same within the sport's premier annual championship

It’s a World Cup year, so the Six Nations means more, right? That’s not what any of the coaches are saying, nor the players, and while it’s always easy to ignore what they are saying and guess what they might actually be thinking, maybe they’re right.

As the Six Nations kicks off tonight, it’s important to look at the two reasons that support this. The first is a factual one. The second, well, that’s much more up for debate - but we’ll get to that.

It’s not hard to look at the prior record of Six Nations winners when it comes to the Rugby World Cup. Not since England went on to claim global domination in 2003 has a Six Nations winner reached the final. And while it’s unlikely to be the case that the tournament takes too much out of the winners given that there is six months between the end of the championship and the start of the World Cup, it is clear that there are few positives to take out of it beyond the feel-good factor of victory itself.

In 2015, Ireland found that the squad who were good enough to win the Six Nations was not deep enough to withstand a crippling injury crisis, while in 2011 England managed to go from European champions to World Cup embarrassment via dwarf-tossing and ferry jumping. Even in 2007, when France and Ireland finished level on points at the top of the table, it was England who came forth to reach the World Cup final and nearly pull off the shock of all shocks.

Plenty will happen between now and the end of the Six Nations on 16 March, and plenty more will happen between 17 March and 20 September when the curtain raises in Tokyo. Players will be ruled out through injury, or suffer dips in form, while others will emerge to take their place. Those are the sad facts of World Cup year.

But this does not diminish the Six Nations. Far from it.

This is a championship unlike any. The Southern Hemisphere equivalent, the Rugby Championship, is no match for the Six Nations, and not just by its numerical advantage. It is a tournament built on historical rivalries, on years of being wronged or conquered, and where once it was arrows or bullets or bombs used in combat, now it is full-blooded tackles that are the weapon of choice. That is not to say that what happens on the fields of the Aviva Stadium or Stade de France or Twickenham is akin to war, but the feeling that resonates within the Calcutta Cup and the Anglo-French battles is one steeped in history.

Most, if not all, matches will be sold-out affairs, something that the Rugby Championship cannot boast, as fans clamour to see their country both home and away.

And it is almost astonishing to see how far the tournament has come in the space of 20 years. When the expansion from five to six took place in 2000 with the adoption of Italy, the tournament was pretty much a two-team affair between England and France for top honours, with Ireland, Wales and Scotland looking to emerge as the best of the rest while avoiding the banana skin that is Italy.

Somewhere along the line, things got serious. Wales first emerged as the new boys on the block with the 2005 Grand Slam, something that was strengthened enormously by the appointment of Warren Gatland in 2008. Then came Ireland, who in 2009 got the 24-year monkey off their back by claiming the title, and a Grand Slam to boot. In the 10 years that have passed, Ireland have gone from strength to strength to emerge as the leading country within the Six Nations, winning three of the last five tournaments and defeating New Zealand last November in what is the biggest threat that the All Blacks have faced to their dominance in the last decade. The Irish will be determined to prove that last year’s Grand Slam was no fluke, which may just help them through any complacency that crops up along the way.

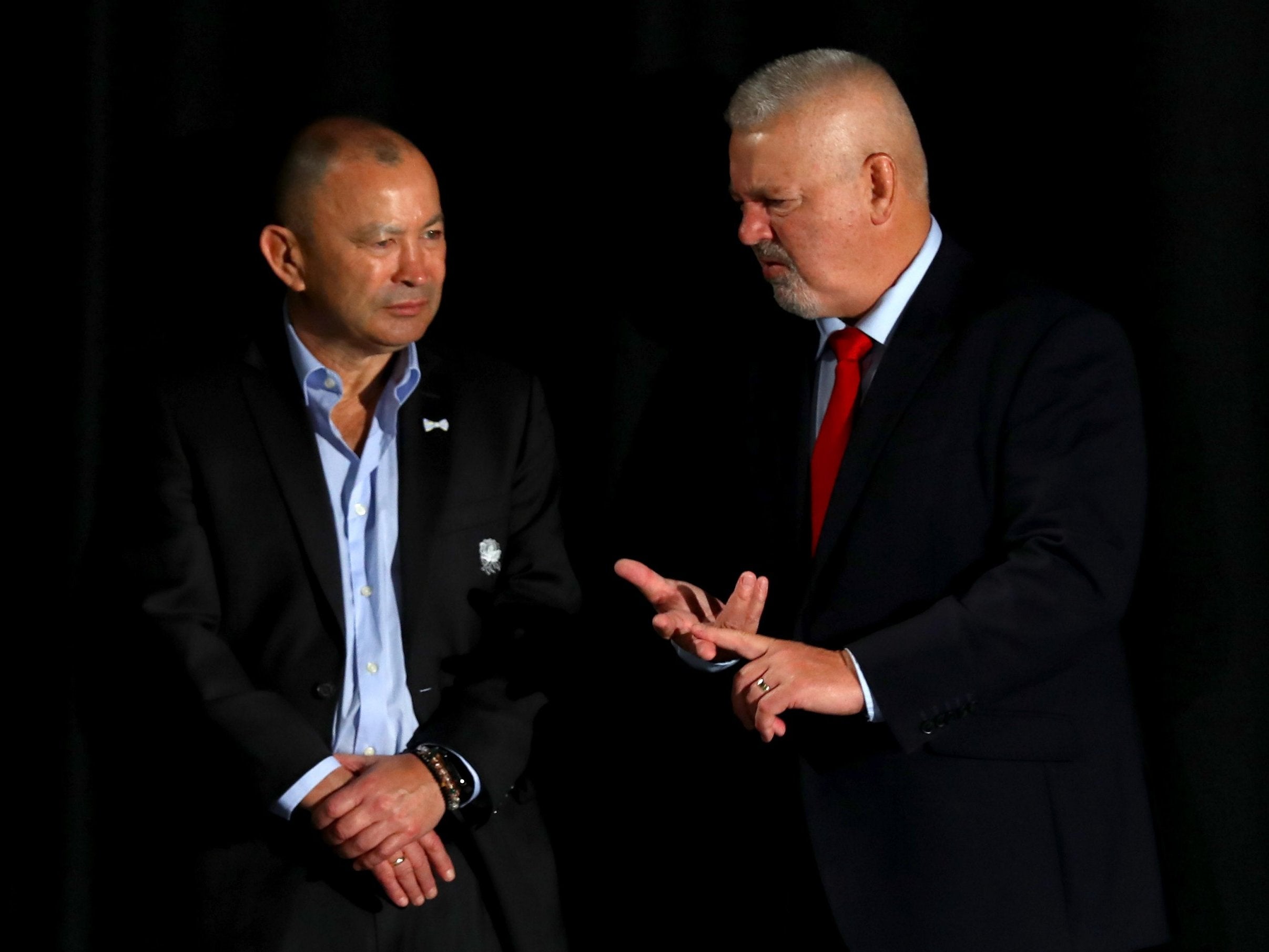

This will also be a year of goodbyes. Gatland and Joe Schmidt will both leave their roles at the end of the year, meaning that beyond the meaningless World Cup warm-ups in the summer, this is the last time they will coach their respective nations on home soil. Eddie Jones could also be on his way, with a break clause in his contract active after the Rugby World Cup and the man himself doing little at the Six Nations launch last week to suggest he will still be England coach next year. The futures of Jacques Brunel and Conor O’Shea are similarly uncertain to say the least.

No one will want their Six Nations careers to potentially end with a wooden spoon or an anonymous bottom-half finish, and where the players are professional enough to shut that out from their minds, how will the coaches handle the emotion?

Over the course of the next seven weeks, we will find out.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments