James Lawton: Federer marvels in his second coming

The Australian Open champion's skill to reinvent his game and win a 16th Grand Slam title sets him apart from the greats of other sports

The great champions, men like Muhammad Ali and Jack Nicklaus, have always shared an ability to reach down and find again qualities that the world believed lost forever.

But it is not often they do what Roger Federer did in Melbourne. They do not re-make themselves quite so remarkably. They tend to fall short of re-incarnation. Federer did not.

Astonishingly when you think of all that he has achieved, in both victory and defeat, Federer's latest gift to the sport he has dominated so profoundly, so beautifully for so long carried more than anything the element of surprise.

Not a surprise, of course, that he beat Andy Murray. Even if you had a misplaced hunch that it might be the time of the brilliantly gifted 22-year-old Scot, that his apprenticeship had been supported by both original talent and steadfast application, you could not dispute Federer's status as favourite. To do so would have been both rash and impertinent.

What you also could not do, though, even if you were his most fervent admirer, and the highest reaches of his extraordinary march to a record 15 Grand Slam wins before yesterday were imprinted indelibly into an understanding of what constitutes the essence a champion among champions, was imagine that he could produce a performance so complete, so inexorable.

One, indeed, that was so vital, so imbued with the idea that he was no longer pursuing one last hurrah but a whole set of new horizons. Apart from anything else, Federer made time stand still.

At the age of 28 he has surely done more than stretch out further the target facing anyone who in the future makes the improbable assertion that he has the means to be the greatest tennis player of all time. He has done nothing less than consolidate his claims as the supreme phenomenon of modern sport.

Federer is someone whose consistent hold on such imperatives as fitness – a great, often ignored attribute, we were reminded as his 22-year-old opponent showed clear signs of physical stress in a near heart-stopping third set and tiebreaker – relentless practice and unswerving dedication to the avoidance of any distraction has outstripped all opposition not just in tennis but any sports discipline you care to mention.

There was a time when his level of performance was inextricably linked with the deeds of his now embattled friend Tiger Woods. But for the moment at least such comparisons are not so much remote as savage.

There, in Melbourne, was Federer, the ultimate sportsman, the adoring father and the devoted husband. And somewhere shielded from the gaze of a judgmental world was the Tiger, engaged in of all things, we are told, a battle against an addiction to casual sex. No-one should easily dismiss the capacity of Woods to re-generate the splendour of his golf, or reproduce the mental toughness that once enabled him to share the peaks of sport with the man with whom he regularly exchanged text messages of mutual congratulation. But then it would also be idle not to believe their current situations might be residing on separate planets.

So much about Federer in Melbourne was so stunning it is not so easy to isolate one over-riding quality, beyond the obvious bearing and technique of a born champion.

The precision of his shot-making was quite surgical. His timing sometimes belonged to another world of magic touch and instinct.

There were occasions, no doubt, in the third set when the level of his performance lagged to the point where it was reasonable to believe that from somewhere inside this maestro's clinic Murray might at least rescue some sense that his challenge was not utterly foredoomed. But even then, the odds against the Scot applying sufficient pressure on Federer to challenge this reality were essentially hopeless.

Federer simply had too much in reserve. Too much understanding of what he was doing, which was basically to discourage at the source the ambition and the optimism of his deeply-gifted young opponent.

Apart from beating Murray and, the fear must be, threatening some fundamental self- belief, Federer was overturning an impression created inevitably by his epic defeat by Rafel Nadal at Wimbledon in 2008.

Then, we saw a marvel of defiance, the vow of the great champion that if he was indeed at the end of something, he would not go quietly and he would not go without more than a little passing evidence that for quite some time he was the best tennis player anyone had ever seen.

There was more than enough of that, and most memorably a backhand drive down the line that sounded like a rifle shot and was fired at the heart of Nadal's understandable belief that he was in the process of inheriting the tennis world. One reason to believe that was earlier in 2008 in Paris the Spaniard had beaten Federer with eviscerating power and athleticism.

So after Federer subsided, and said that he was proud to have been part of such a Wimbledon final, even if it had brought him his first defeat in six attempts, we had a new role for Federer. It was of the still sporadically brilliant, declining champion, by no means guaranteed, with the arrival of Nadal with such force, the three more Grand Slam victories required to pass the record of 14 wins set by Pete Sampras.

It was a role hardly stripped of nobility, the artist fighter contemplating the dying of his light, and though he surpassed almost all expectations except his own by reaching the historic mark with wins at the US Open, the French for the first time, and Wimbledon yet again something still said that here, still, was a talent riding home rather than seeking to occupy new terrain.

That idea was ridiculed in Melbourne. No, Federer wasn't running out the string. If anything, it was a band of steel.

Given his jibe – after winning his semi-final so majestically – that Murray had to deal with the pressure that came with representing a nation that had not won a Grand Slam event for about 150,000 years, we don't quite know how kindly Federer meant his tribute after yesterday's triumph. He said to Murray, "You played well, you're too good a player not to win a Grand Slam." From a man who had just won his 16th, it was perhaps not quite the accolade Murray might have singled out in the Australian dawn, and some might say there was at least a hint of the patronising.

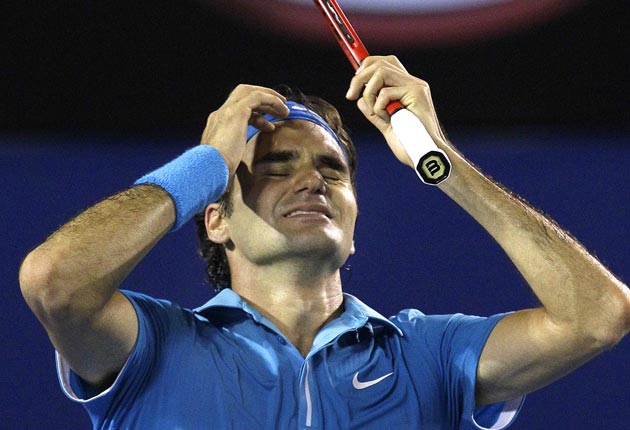

Murray, no doubt, was a little too broken for the deepest analysis when he said, before a crushing onset of emotion, "I can cry like Roger, shame I can't play like him." But then who ever played tennis like Roger Federer? Who ever waged sport with quite such facility and poise, with quite such a belief in his own power to find a way to win.

At the start of this decade there was a a viable case for the 24-year-old Woods, as they might be again one day. Naturally, it was an argument that provoked intense opposition. Golfers do not risk having their heads caved in, not like an Ali or a Sugar Ray Robinson. They hit a stationary target. No doubt claims on behalf of Federer, now he has extended his lead over Sampras, will produce similar dispute. Tennis players are separated from their opponents by a net.

Yes, it is true we are not comparing like with like. But maybe we can make one valid assertion when attempting to nominate the greatest of sportsmen. It is when we measure the dominance an individual has achieved within his own discipline.

Have his achievements flown above those of all his rivals? Have they defined the best of the sport, brought it to a new dimension?

Watching Federer remove, temporarily we can only hope, the heart of Andy Murray, who is generally agreed to be currently the most purely talented of his young challengers, was to lean strongly towards such a belief.

What can't be made is any absolute assumption about the meaning of Federer's victory, whether it was indeed a startling statement about the regained momentum of a once fading champion or another act of extraordinary defiance against the march of time.

However, if we cannot indulge Federer in the hope he has created for himself in such an exquisite way the danger is of a charge of ingratitude. The champion, after all, not only enlarged an already huge reputation. He enriched the possibilities of every corner of sport.

Fed Express: Roger's roll of honour

*Australian Open 2004, 2006, 2007, 2010

*French Open 2009

*Wimbledon 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009

*US Open 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008

*Federer extended his lead at the top of the Men's Grand Slam list:

16......... R Federer (Swit)

14......... P Sampras (US)

11......... B Borg (Swe)

8......... A Agassi (US), J Connors (US), I Lendl (Cz)

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies