US Open’s new shot clock is sport’s latest misstep away from the epic and the timeless

The time limit is founded on a surprisingly tenacious myth: that time is an objective scientific measurement, and thus the same for everyone. It’s nonsense. Time is almost entirely subjective

Over the years, the concept of time as a form of currency has become a popular trope of science-fiction, from the 2011 Justin Timberlake film In Time, to a 1987 short film called The Price of Life, and Harlan Ellison’s 1965 story “Repent, Harlequin!” Said The Ticktockman. In the latter, human society is run according to a rigid schedule, in which being late is not simply a discourtesy but a felony. Misdemeanours are punished by the eponymous Ticktockman, the all-powerful timekeeper who has the power to deduct time from people’s lives, or in extreme cases terminate them altogether.

The dystopian world Ellison envisaged, in which humans are tyrannised by time, their lives ruled by endless, innumerable clocks, is one no longer recognisable solely as fiction. As technology has increased both the ease of measuring time and the number of things we can do with it, our daily existences have become like a sort of ticking prison, in which we are constantly being told, for one reason or another, that our time is running out.

By way of illustration, try counting the number of clocks in your house. From where I sit now I can see the oven, the laptop, the dishwasher, the washing machine, the stereo (why??) and – rather quaintly – the clock. And that’s before we even get to our phones, perhaps the real world’s closest equivalent to Ellison’s terrifying Ticktockman, draining our time while also chiding us for our loss of it, usually by reminding us of some terribly important thing that simply must be done at some very precise point in the near future.

Time, the eternal x-axis, has somehow become the y and the z as well. Everyone is busy, all the time. Time management – an utterly odious concept – has become one of the core skills of modern humanity. Even the most minuscule, inconsequential aspects of our lives are governed by it. Click on your latest software update and you will be confronted with a wildly speculative estimate of how long it will take to finish (“Nine minutes! Eight minutes 48 seconds! Eleven minutes! Two days!”).

A lot of blogs and websites now provide an estimated reading time for their articles. (This one: probably about five minutes, although you could definitely skim it in three.) And I’m sure I’m not the only one here who chooses my Netflix movies on the basis of length. This explains why I am still yet to watch The Godfather, haunted and comforted by the knowledge that in the three hours it would take to watch Marlon Brando mumbling long sermons about the American Dream, I could watch two of the three Naked Gun films, and almost invariably will.

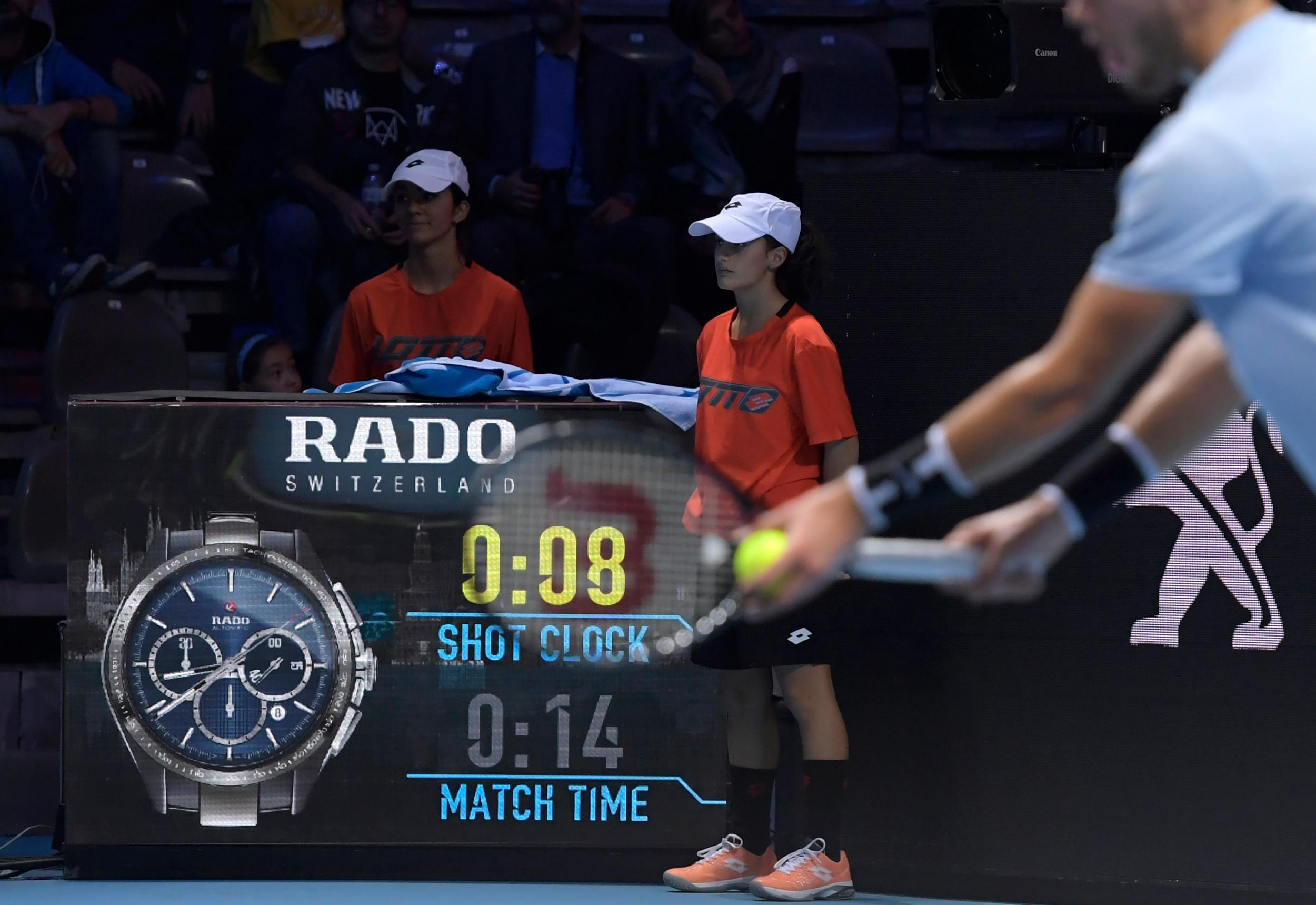

All of which brings us, in an ironically protracted sort of way, to the US Open, which announced this week that it will become the first of the grand slam tournaments to introduce a shot clock for its main draw. Players will now have 25 seconds to serve – and always did, of course, under existing time violation rules. But now they – and the crowd – will be able to see the clock ticking down, and if they fail to deliver their service within the allotted time, they will lose it.

“We are concerned about the pace of play, as all sports are,” explained Chris Widmaier, managing director of the US Tennis Association. And in a way it is no surprise that this latest innovation has come from the United States, which loves nothing more than gawping at a spurious sporting clock, whether it is the pointless two-minute warning in NFL or ice hockey’s Byzantine book of time penalties – minor, double-minor, major, misconduct – that have generated an entire statistical sub-genre of their own.

But in a way, the shot clock is emblematic of a broader trend within sport, away from the epic, the timeless, the open-ended, and into the fixed, the bite-sized, the measurable. Put simply, sport is getting shorter: a move initially driven by broadcasters, who have schedules to fill and like knowing exactly when something is going to end. But now it seems the clamour is coming from paying spectators as well, who also have schedules to fill, and for whom live sport increasingly resembles a Tetris block to be slotted into the multicoloured morass of their packed, unfulfilling lives.

Other sports are already discovering this. Test cricket has been losing ground for some time now, as the general public begins to tire of a game that could take five days, or maybe three, and could finish at 6pm, 6.30pm, 7.30pm or at any time before. Television ratings for golf in the US have been declining for a generation, with the scourge of slow play one of the major factors being blamed.

Then of course, we come to football: a law unto itself, in that a sport that lasts for 90 minutes with only a single break would never make it past the pitching stage these days. And throughout its long and largely conservative history, football has proved remarkably resilient in the face of attempts to gauge and define its time.

The six-second rule for goalkeepers is scarcely, if ever, applied. Nobody really knows how long a football match lasts in terms of ball time, and – despite the begrudging addition of the stoppage time board – nobody really knows how long it will last. The Real Madrid vs Juventus match on Wednesday was supposed to have three minutes of stoppage time. By the time Juventus had given away a penalty, Gigi Buffon had done his best impression of a victim of a Jeremy Beadle prank, Michael Oliver had sent him off, Cristiano Ronaldo had put away the penalty, celebrated and then been booked for his celebration, almost nine had elapsed.

Occasionally you will hear calls for football to standardise its measure of time. The game’s lawmakers are already mulling over a proposal to reduce the length of the game to 60 minutes, with the clock stopping whenever the ball goes out of play. It’s a bad, bad idea. Time-wasting may be a blight on the game, but a minor one in the grand scheme of things, and one punishable under existing laws. Once the clock stops, there is no way of telling when it will start again. Broadcasters have been trying to sneak adverts into football for decades. How long until stoppages become scheduled breaks, and matches begin to swell to two or even three hours?

The US Open’s serve clock, too, may end up having unintended consequences. When it was trialled in the qualifying competition last year, some players sped up, but others actually started taking more time over their serves once they realised they still had several seconds left. Once you introduce a clock into somebody’s life, it becomes impossible to ignore entirely. Time becomes its own, creeping protagonist.

But the real reason to oppose the long, ominous march of timekeeping is ideological rather than logistical. In a world ever more closely defined by the strictures of time, so it becomes all the more important occasionally to defy it, to generate the illusion of the eternal, to forget. Great art can do this. Great sport, too. And whether it is the roof of the Sistine Chapel, the unforgettable all-night flat party or Djokovic vs Nadal at the 2012 Australian Open, so many of our greatest achievements, so many of our fondest memories, are forged when time takes a back seat.

“If you want to play well, you have to let players breathe a little,” says Nadal, one of the shot clock’s leading opponents. “We’re not machines. If you want to have matches like I played with Novak, you cannot expect to play 50-shot rallies and in 25 seconds be ready to play the next point. But if you don’t want a great show, of course it’s a great improvement.”

The time limit is founded on a basic and surprisingly tenacious myth: that time is an objective scientific measurement, and thus the same for everyone. It’s nonsense. Time is almost entirely subjective, a sensation dependent largely on circumstance and context. And if there’s any doubt about that, then spend five minutes on your phone, then turn it off for five minutes, and compare the two experiences.

Let’s say the US Open manages to shave 10 minutes off the average match. What would people use it for? Probably to go on their phones and do useless tasks they didn’t need to do in the first place. The illusion of modern life is that in regimenting our time, we will give ourselves more of it. Perhaps, instead, we’re giving ourselves less. Perhaps it’s time we stopped playing along, stopped measuring, stopped parsing, stopped living our lives in the menacing and inescapable shadow of the Ticktockman.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks