Could this be the end of the MBA as we know it?

Courses are radically changing with the times – with some interesting and surprising results, says Michael Prest

Does the Master of business administration qualification have a future?

It seems a perverse question. Business schools are multiplying around the world, applications from students to study for the degree are buoyant and business’s need for better- trained managers has never been greater. Yet many schools are agonising over the nature and purpose of the degree. Adjudicating between the rapidly changing requirements of students and business is proving hard, while there is rumbling criticism that the MBA has become a victim of its own success, hobbled by a stagnant core curriculum and a conservative accreditation system.

The MBA is a survivor. A doughty centenarian, it has no shortage of supporters. “I am old enough to have heard harbingers of doom about the MBA on many occasions. The MBA is probably the most successful postgraduate degree ever. It’s a key degree programme for creating the future,” says Professor James Fleck, dean of the Open University (OU) Business School.

In a recent paper, To MBA Or Not To MBA, Professor Yehuda Baruch, of Rouen Business School in France, concluded: “The MBA is still flourishing and generating value for individuals, organisations and society. MBA graduates are in general better managers, and their employers benefit from their competencies. Moreover, improving managerial cadre is likely to result in long-term improvement in organisational effectiveness and subsequently an improved economy.”

The view may be biased, but in broad statistical terms the MBA’s success is undoubted. Around 120,000 MBAs graduate in the US each year, along with more than 50,000 in Europe – of which some 30,000 are in the UK. Numbers are also rising rapidly in Asia. Roughly a third of MBA graduates in the UK are female and their ranks are expanding. When top business schools can charge more than £50,000 for an MBA and still have applicants queuing up, students clearly think the degree is good value. But what do those students want?

Are business schools really providing it, or are students, business schools and employers locked into a mutually reinforcing system from which they cannot easily escape? A lot depends on what you think the MBA is for. The simple answer is to make organisations more effective – but what does that mean?

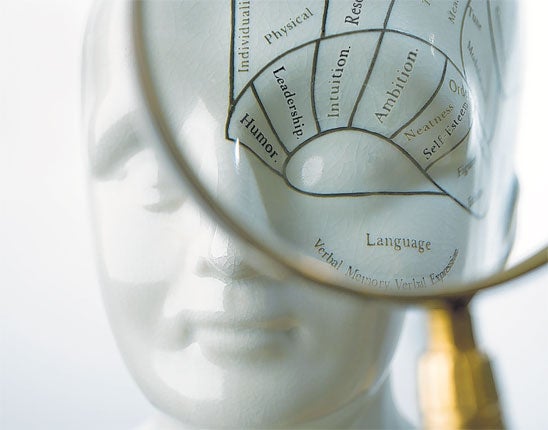

The classic MBA developed in the United States placed considerable emphasis on academic knowledge – finance, strategy, production and so on. However, over the past 20 years, the emphasis has shifted, subtly but significantly. The consensus at last month’s international conference for deans and directors organised by the Association of MBAs, one of the degree’s leading accreditation agencies, was that it should teach leaders to manage complexity.

“You still get the basics. But the important thing is not learning stuff but a way of thinking. We constantly need to be developing people’s thinking skills,” says Dr Sarah Dixon, dean of the Bradford University School of Management.

Shealso stresses another element that an earlier, less touchy-feely, generation of business academics might have found slightly embarrassing. “The personal development you undergo is huge. Most of our alumni say they changed as a person as a result of the course.”

These shifts are explained as responses to what business needs. They certainly reflect a world in which the pace of innovation and change appears to be relentlessly accelerating and the volume of information is overwhelming. If the future is ever-harder to predict, learning how to sift the important from the unimportant, the genuinely novel from the merely new, is a valuable skill. To the extent that organisations, the ultimate MBA customers, want that the students will too.

Adapting the purpose of the MBA, however, also places strains on what is taught and how. There are three main pressures on what is taught. The first is the notoriously intense curriculum. Covering fundamentals such as finance, strategy and change management does not allow much room to cram in the fashionable newer themes of sustainability, entrepreneurship and ethics, in which more recent generations of students are interested and which have come further to the fore since 2008’s financial crisis.

Entrepreneurship, for example, is not just about graduates starting their own ventures. It also appeals to students training to return to the family business.

“Some of our students are going off to run the family business,” says Dr Jane Tapsell, dean of the University of Buckingham Business School. This is especially true of Indian students. Moreover, entrepreneurship – defined as spotting and exploiting opportunities – is not confined to the private sector.

“There is growing recognition in companies and public sector organisations of the importance of people who can take the initiative, come up with creative ideas and have the ability to see ideas through,” says Christos Kalantaridis, professor of entrepreneurship and innovation at Bradford University School of Management.

The second problem is vested interests. The standard core MBA curriculum has bred several generations of academics threatened by change. The curriculum is often criticised from inside business schools, as well as outside, for being divided into “silos” between which the connections are weak. “We created long thin strips rather than short fat blocks,” says Dr Tapsell.

To some extent, the accreditation system may have exacerbated this problem. Most business schools are reluctant to publicly criticise the accreditation agencies, on whom they depend for the vital stamp of quality. But deans privately are less complimentary. At the least, there is concern that accreditation has hampered innovation. Some see a tension between maintaining standards – which is undoubtedly critical – and being sufficiently flexible to adapt to a fast-changing landscape. For their part, some business schools accept they do too much esoteric research.

Perhaps the biggest pressure on the curriculum, however, is intellectual in the sense of fundamental ideas. Like the finance industry that business schools have faithfully served, the MBA curriculum has given great credence to the efficient market hypothesis. Put simply, the theory that one cannot achieve returns in excess of average risk-adjusted market returns for long because, for example, prices reflect all publicly available information. The financial crisis threw a long, dark shadow over this theory and prompted some soul-searching among schools about whether they had snuggled up too close to their subject, business, and not kept a decent academic distance.

Warwick Business School has taken the lesson particularly to heart. It has set up a behavioural science group, headed by Professor Nick Chater, a psychologist. The group draws on a range of fields that challenges economic orthodoxy by suggesting, for instance, that individuals do not make “rational” decisions based on a carefully calibrated assessment of risk and reward. The school's dean, Professor Mark Taylor, says he wants behavioural science to be central to the MBA.

This bold step could be the first fundamental intellectual overhaul of the MBA in a long time. Moreover, Taylor is also keen on developing “soft skills” and placing less emphasis on technical skills such as accountancy. Soft skills can be derided, but the phrase also points to a real difficulty: the MBA has become imbued with an Anglo-Saxon perspective. Soft skills mean, among other things, appreciating how other cultures with different institutional structures tackle problems. Jeitinho, a Brazilian term for an informal way of negotiating around conventions and procedures, is cited, not least because it resonates with common experience that parallel social structures in organisations are just as important as official procedures for achieving results.

Illustrating the growing interest in creativity, Warwick has joined forces with the Royal Shakespeare Company to set up an RSC/Warwick Centre for Teaching Shakespeare. Encouraging creativity in business schools is not new.

Other institutions are also forging links with art and theatre. The combination of behavioural science, soft skills and creativity is probably not one the MBA’s originators would have imagined.

Several other business schools have also recently overhauled their courses. Nearly everyone is talking about “integrating” the traditional MBA and breaking down the silos. The OU is building entrepreneurship and creativity into its whole curriculum; Bradford has remodelled its course into concentrated blocks. At the other end of the spectrum are specialist MBAs in areas such as energy, health, fashion and the law. Some MBAs, especially executive degrees for part-time study, are tailor-made for employers.

Purists are suspicious. “I’m not a huge fan of the specialist MBA. If you want to be a general manager and leader of an organisation you need a broad management degree,” says Dr Dixon.

Most controversial is the movement towards MBAs that do not require work experience. This subverts one of the sacred tenets of the traditional MBA and is anathema to accreditation agencies.

Yet the demand is strong, especially from countries where families invest in members to complete their studies quickly and start demonstrating the benefits in the family business. Buckingham is replacing its post-experience MBA with a pre-experience one. “It’s the currency in India and China to have an MBA before they start work. We think there’s a market for this MBA,” says Dr Tapsell.

The MBA also faces competition from other degrees. Business schools are to an extent cannibalising their product by offering a vast array of specialist Masters degrees. An employer needing a finance expert may well be happy with a candidate with an MSc in finance and less interested in an MBA, although that degree has normally devoted quite a lot of time to finance. The MBA remains the flagship, but students are usually canny consumers and for some a Masters could be better value.

Regardless of content and intellectual basis, schools are also experimenting with different ways of teaching. The highly international nature of business education – reflecting the global nature of business – has its counterpart in a proliferating web of cross-border alliances.

The OU is working with the Arab Open University, partly to extend business education to groups who might otherwise be excluded. Bradford has signed an agreement with the engineering faculty of the University of Perugia, Italy, to launch a joint MBA degree. Cross-border collaborations are partly a defensive strategy. In the longer term, home-grown business schools in emerging markets are likely to improve. As the economic centre of gravity tilts eastwards it should not be assumed that the Anglo-Saxon model of business education will prevail indefinitely, even if it does enjoy the flattery of imitation at the moment.

The MBA or something very like it is likely to survive, however, if only because of grade inflation the world over. But it will probably be more diverse in content, character and location than the somewhat formulaic degree that has ruled the roost so far.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks