Mozambique: For the really wild show, look north

Mozambique's Niassa Reserve is a huge parcel of pristine bush where you're likely to encounter animals, but not other tourists. Emma Thomson finds a suitably secluded base at Lugenda Wilderness Camp

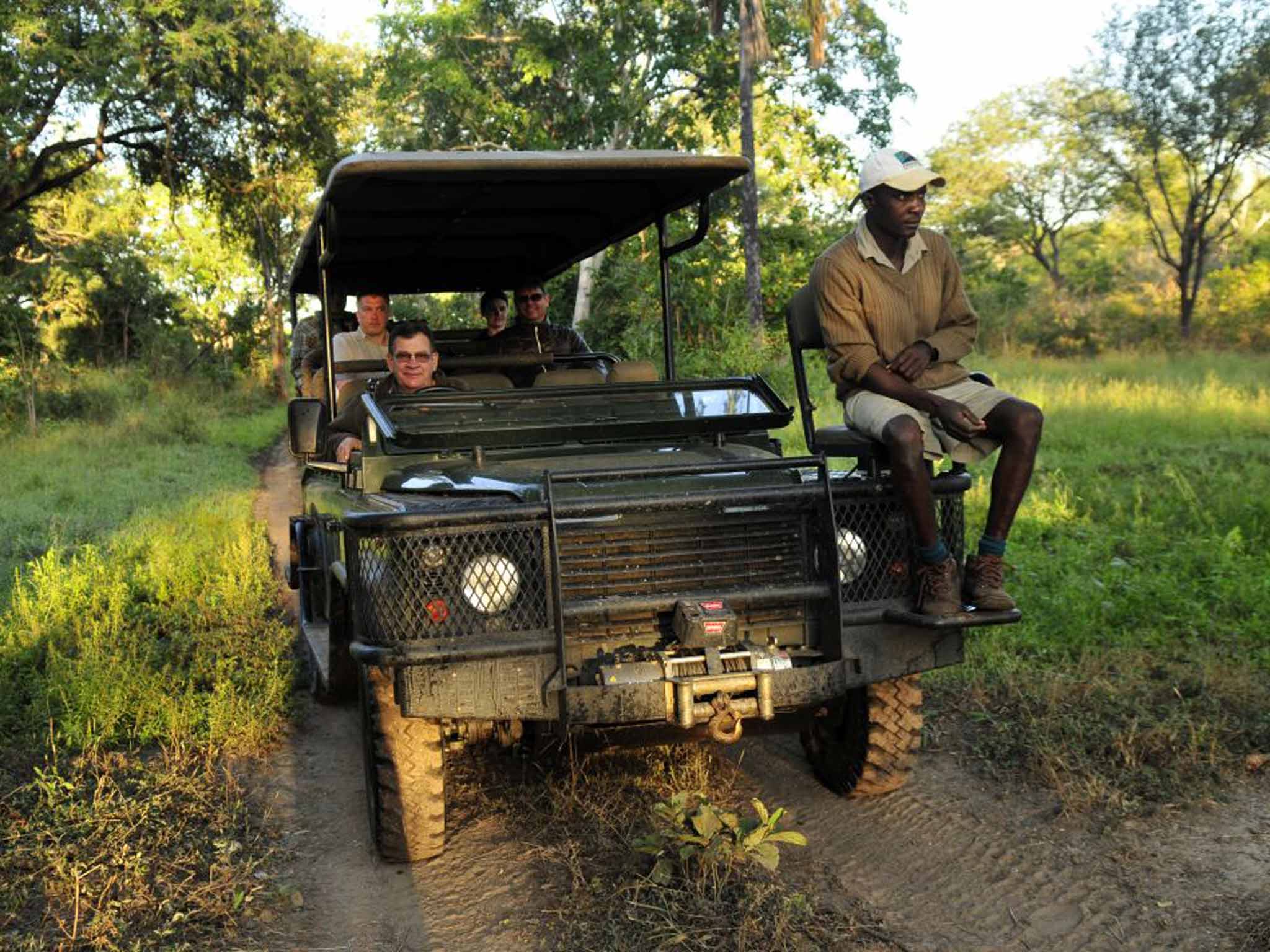

I'm becoming an expert in poop. Elephant poop. "That one looks fresh!" I say, pointing excitedly to a steaming dollop directly in the path of our 4x4. "Mmm … it is," mumbles Nick, our South African safari guide whose voice rumbles low like a lion's. "It's less than an hour old," he concludes, scratching his chin stubble. And a little further down the track: "Ah, this was a female: see how the pee is beside the dung? If it was a male the pee spot would be at the back here," he explains.

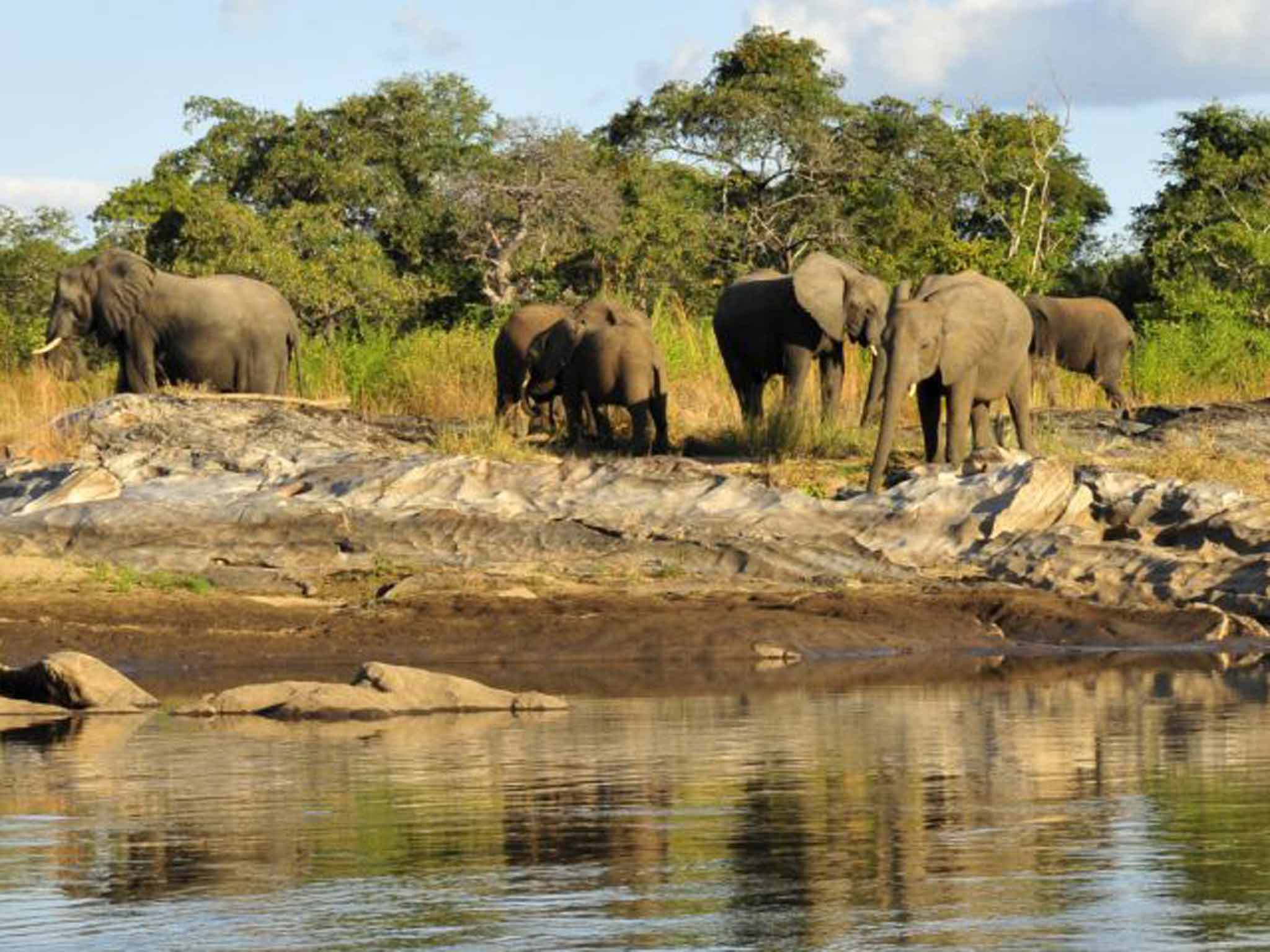

The turd trail veers left and as we trundle right I sit back in my chair convinced we've lost the track, especially among the human-height grasses that have sprung up after the rains. But then we round a corner and, protruding from behind a large bush, there is the glint of ivory. A massive bull elephant steps on to the path just metres in front of us – ears flapping like giant grey towels. Caught by surprise, he stamps his foot and starts charging towards us. Jamie, our scout sitting out front, sits bolt upright in his chair and we hurriedly reverse backwards. Suddenly, the bull skids to a halt, gives one last defensive huff and strolls into the bush, the first dark oozes of temporin dribbling down his temples tells us he's in musth – a testosterone driven violent cycle in bull elephants.

We were on safari in Niassa Reserve, a Switzerland-sized parcel of pristine bush in northernmost Mozambique. Conservationists have called it one of Africa's "last wild places", and seated among this untamed tract of forest is Lugenda Wilderness Camp – a luxury safari lodge with conscience.

It's accessible only by plane, and our six-seater had flown low past rounded mountain hulks known as inselbergs; its white wings coasting the air currents like an egret. Just ahead, I could make out the runway – a scratch of red dirt among endless florets of green trees. "I'm going to take a pass over the runway before we land – there might be elephants and impala milling around," our young Portuguese pilot, Jorge, had warned.

The elephants can mill around all they want here: Lugenda's sector of the reserve is currently the only one designated for photography. The other eight continue to operate as hunting camps because the government still relies heavily on the money to rebuild after the civil war that raged from 1977 to 1992. It's tragic to learn that despite ongoing high-profile conservation schemes, there are still plenty of customers who get kicks out of hunting and shooting their own trophy elephant and are happy to pay the US$100,000 price tag.

Furthermore, poaching remains a big problem. Spurred on by the Asian demand for tusks, poachers are entering isolated Niassa to risk their lives for a big payday – ivory sells for about US$80 per kilo, rising to US$2,000 at the end of the retail chain. Conservationists estimate two elephants a day are being killed on the reserve.

Lugenda isn't taking the problem lying down. If you're looking to get away from it all, its eight luxury tents strung along the sandy Lugenda River are entirely idyllic, yes and the food is scrumptious too, but Lugenda – and its paying guests – serves a more important purpose. The set-up indirectly helps to pay for anti-poaching scouts. The lodge and surrounding lands are owned by Saudi Arabian billionaire Sheikh Adel Aujan, who matches the half-million dollars raised annually by the Wilderness Foundation to keep Lugenda a non-hunting sector and pay for the training and salaries of anti-poaching rangers.

I was still baffled, though, by the persistent mistruths about the powers of powdered ivory and rhino horn despite valiant conservation efforts. "We had a Chinese journalist visit us a few months ago," Nick relates. "And I asked her: 'Why do people still want it, when it causes the death of a beautiful animal?' She told me that the people in China believe elephant tusks are shed; that they're just picked up in the field!"

I question whether it's possible to patrol an area bigger than Ireland in order to stop poaching. "It's true. At the moment we only have 57 scouts – but looking for tell-tale fire smoke at night is the most effective method. About a month ago, our scouts spotted the smoke trail from a poacher's camp, so we went to investigate and they started shooting at us. We had to return fire. We wounded one and the rest scattered. Exploring the camp we discovered an unusual mound of earth and when we cleared away the dirt, buried underneath were 22 tusks. We handed them and the poacher over to park headquarters. The poacher was fined and could be jailed for eight to 12 years."

We meet up with Carlos, the Portuguese camp manager, for dinner. I'm taken aback to learn he once worked as a hunter: "I started in the hunting business because there was always the challenge of getting close to the animals, but every time we shot one, I felt like I was losing something, so I stopped three years ago."

Surprisingly, his viewpoint is still rare. Nick reckons that among the 57 scouts, only six or seven are emotionally invested in the cause of conservation; the rest simply view it as a well-paid job. But positive steps are being taken: I'm told that a a couple called Keith and Colleen Begg, based across the river, run a lion-monitoring project and are building a school that incorporates conservation lessons into the curriculum to improve attitudes and awareness in the next generation.

We rise at dawn and set off through the flaxen grasses, the tips of which are aflame with the first rays of light. Blister beetles helicopter around bushes of wild sweet pea. Joggling past an Amarula tree, I notice that the surrounding grass has been trampled flat; the bark grazed smooth by elephant buttocks. "They shake the trees to get the fruits down – they love them!" laughs Nick.

After about an hour we come across a female elephant with a teenage daughter and an infant. She points her trunk at us like a periscope and lets out a loud trumpet, warning us to steer clear. "She's a real battleaxe, that one," says Nick, with a hint of pride. Turning her back on us, she nudges the youngster and it trots into the scrub, trying not to trip on its little trunk.

For the whole day, we are the only vehicle on the move. The sightings and species in Lugenda may be relatively rare compared to, say, the Serengeti. There are no cheetah, giraffe or black rhino here. But the encounters are all the sweeter thanks to the absence of crowds and the exploratory nature of the safaris: we can swap from four-wheel drive to travelling on foot at a moment's notice.

On my last night, Nick coaxes the 4x4 up a kopje for a final sundowner. Perched atop the rocky outcrop, we look down over the mercury sliver of the Lugenda River. Below, we can make out the minute silhouettes of fishermen casting their nightly nets, and we can hear the deep portly chuckle of hippos echoing along the valley. The vast bush stretches, unbound, all around us. I find myself looking for skeins of smoke trailing upwards from a possible poacher's campfire, but see none. For tonight, this is a good sign: change may be slow, but thanks to the efforts of camps like Lugenda it's a step closer. Those who choose to take photos rather than tusks play their own small role in that.

Getting there

Emma Thomson travelled as a guest of Found Travel (020 8123 1377; found.travel). She flew from Heathrow to Maputo via Lisbon with TAP (0845 601 0932; flytap.com) and from Maputo to Pemba with LAM (020 7107 2303; lam.co.mz). From Pemba, Lugenda Wilderness Camp can arrange a 90-minute light-aircraft transfer to the camp.

Staying there

Lugenda Wilderness Camp (00 27 83 642 1663; lugenda.com). Double tents cost from £700 per night, including all meals and drinks, safari and park fees.

The red tape

UK nationals require a visa; a single-entry visa, valid for 30 days, costs £40 from the High Commission of Mozambique, 21 Fitzroy Square, London W1T 6EL (020 7383 3800; mozambiquehighcommission.org.uk).

More information

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks