The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

South Africa's bright future

Twenty years after the nation held its first democratic elections, Cape Town is using its World Design Capital status to look to the future, says Chris Leadbeater

Just inside the hotel lobby of Mandela-Rhodes Place, in the heart of Cape Town, a sunny statue of Nelson Mandela greets anyone who wanders through. At first glance, I am sure there is something odd about this life-size figure. And at second glance too. It is the grin. Too broad, too eager, it seems to reduce one of the 20th century's most significant political heavyweights to an avuncular caricature – as if all he ever did was smile for the cameras.

Today, is a reminder that he was more than a friendly face. While there were many red-letter dates to the great man's story – his notorious arrest (5 August 1962); his celebrated release (11 February 1990); his much-marked passing last year (5 December) – there is a credibility to the thought that 27 April 1994, 20 years ago today, was the most crucial.

This was the moment that South Africa finally went to the polls in an open, multiracial general election – a procession which would lead to Mandela's inauguration as the country's first black president, the detonation of the apartheid regime that had strangled much of the nation since 1948 and the dawn of a fresh epoch of hope and equality for all.

Or at least, that is one version. It takes me just 10 minutes and eight miles – cutting west from the airport amid the seething traffic of the N2 highway – to notice that, while South Africa may no longer live with an enforced system of segregation, the financial chasms that still divide it are all too evident. On the left side of the thoroughfare, the township of Gugulethu reeks of deeply ingrained deprivation – corrugated rooftops and close-clustered homes. Almost immediately, on the far side of the camber, Pinelands dozes in a different galaxy, water sprinklers nurturing golf courses, palatial properties behind security fences.

A half-century of internalised rupture was never likely to be corrected by two short decades of democracy and social movement. But such reminders of 20th-century partition are awfully common in South Africa. They are also the reason why this year is such an intriguing one for Cape Town. Africa's most picturesque city is spending 2014 in a global spotlight – and is determined to use the exposure as a spark to change itself for the better.

"World Design Capital" is a relatively new concept, a badge that was first worn by Turin in 2008 and has since been transferred to Seoul and Helsinki, on a biennial basis. Largely, it has worked as a celebration of the visual arts and cutting-edge creativity. But Cape Town, the new incumbent, has rather loftier ambitions – of redesigning itself as a modern metropolis where life has an even-handed flow; of "un-engineering" what racism did to it.

It is a dream that may take 50 years, rather than 12 months, to bring to fruition. But a quick examination of the projects already under way shows the scale of the blueprint.

While the schedule is full of arty endeavours – the Mandela Poster Project Exhibition will bring 100 diverse images of the ex-leader to the city in November and December; Mobile Benches will see seating in dramatic shapes and hues pitched around Cape Town in a bid to make its residents sit and speak to each other – it is the more visionary ideas that strike a chord. One is a careful re-crafting of the shanty area of Flamingo Crescent (in the south-east of the city) to introduce community centres, play spaces and crèches into an area of unplanned sprawl. Project Isizwe will deliver Wi-Fi to poorer communities "for the purpose of education, economic development and social inclusion". Cape Town's Future Foreshore will look to reform the semi-derelict waterside Foreshore district – long cut off from the rest of the metropolis by railway lines – into something more accessible.

There is even talk of re-routing some of the multi-lane roads that were effectively agents of apartheid rule, barriers that physically separated – for example – Langa, Athlone and Pinelands (neighbouring enclaves which, by the rhetoric of this bleak era, were deemed "black", "coloured" and "white" respectively). The whole plan, Alayne Reesberg, CEO of Cape Town World Design Capital, tells me "is as much about the gritty as the pretty".

In many senses, this year of change is an invitation to all – to visit a metropolis that is known, and yet unknown. True, many thousands come annually to glide up the cable car to Table Mountain or sail to Mandela's former prison on Robben Island. But few peer beyond the obvious, at a city, home to 3.7 million, which unfurls as a tapestry of districts.

It is not instantly apparent where to begin. But I find a guide in Iain Harris – a committed Capetonian whose company, Coffeebeans Routes, runs tours into parts of the city that lie beyond the usual tourist borders. These (mainly) half-day trips trace a range of topics – food, art, music. And, in my case, revolution. "We try to show the real Cape Town, even if that means the darkness that forged it," Harris says. So we start by driving to District Six – an area that was admirably integrated until the apartheid powers began sifting its mixed populace. In 1966, when its valuable land, so near the centre, was increasingly coveted, it was declared a "white" area. Families were uprooted, houses torn down. The scars are still visible. While parts of District Six have been resettled since 1994, many plots were never developed and float in limbo as rubble-strewn patches of grass. Adjacent, the District Six Museum recounts the ordeal of the 60,000 residents who were expelled from their homes.

Many were relocated to black townships – among them Langa, seven miles east. Here, the narrative sinks further into gloom. The Langa Heritage Museum occupies a defunct "dompas" office – a bureaucratic bolt hole which issued the hated passbooks that all black South Africans were required to carry when beyond their designated areas of residence, between 1952 and (as recently as) 1986. These apartheid Yellow Stars had to be produced on demand, on pain of arrest, and the museum recalls the anger and shame they caused – notably the widespread protests of March 1960 and the government violence that ensued.

A little further east, Gugulethu also bears the mark of tyranny. On the key avenue of Steve Biko Drive, a septet of granite slabs, each carved with a single human outline, salutes the Gugulethu Seven – ANC (African National Congress) activists, all aged between 16 and 23, ambushed and shot by police on 3 March 1986, young victims of apartheid brutality.

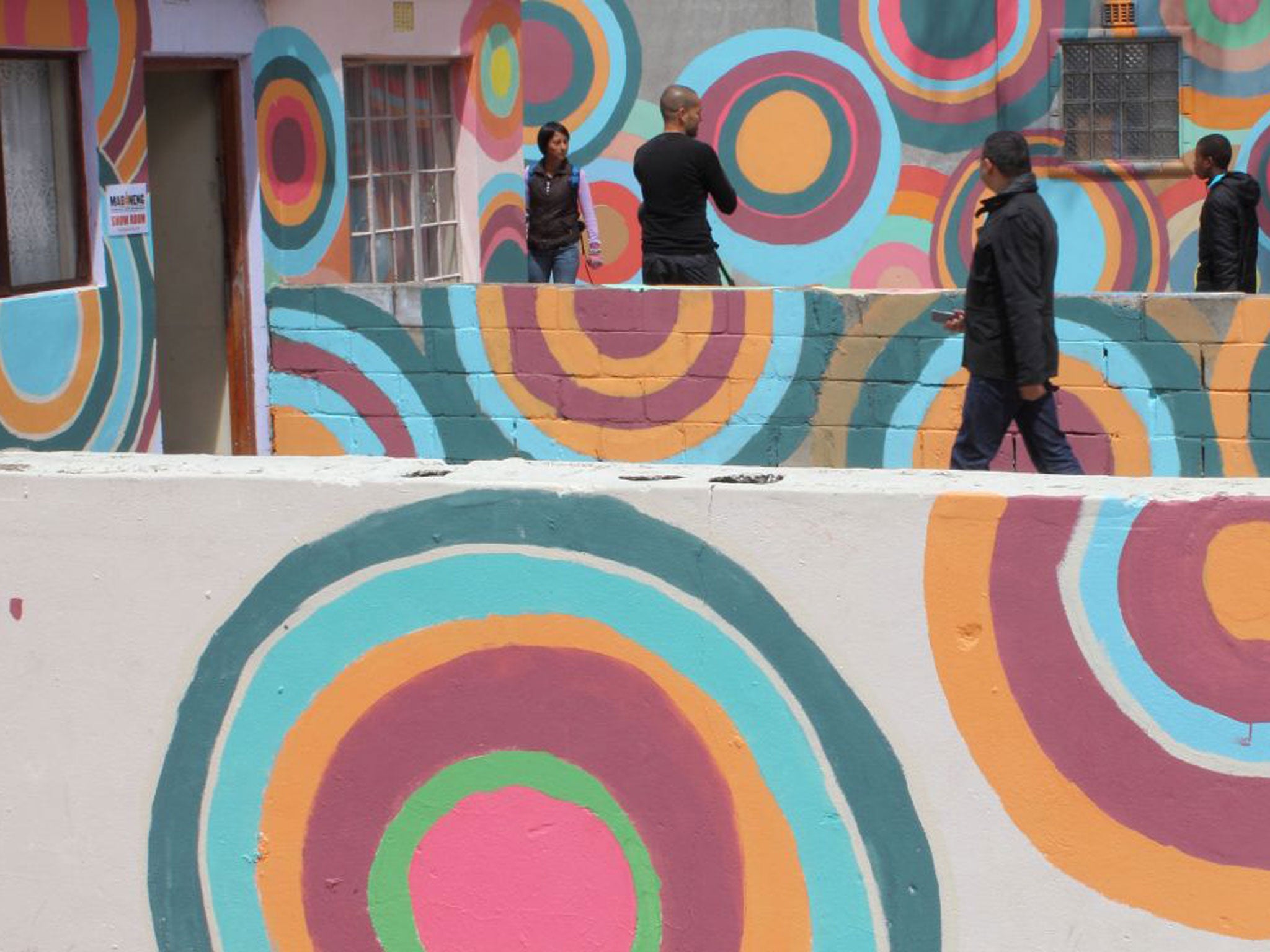

This is difficult to look at. But where the Coffeebeans Routes itineraries stand apart from the often voyeuristic township tours that have become an uncomfortable element of tourism in Africa is in their determination to proffer light as well as shade. Nearby, residential lane NY147 wears the informal name Art Street – thanks to its penchant for turning itself into a temporary gallery under the umbrella of the Maboneng Township Arts Experience. The brainchild of Johannesburg-based artist-musician Siphiwe Ngwenya, this initiative seeks to transform underprivileged areas via culture. Last October, all 23 homes on NY147 lined their walls with colourful canvases – all by local painters, all for sale. "The dream is to see the end of 'township tourism'," Ngwenya says, sketching out his desire that districts like Gugulethu will soon welcome visitors on a more sustainable level.

Maboneng has extended its reach to Langa as part of the 2014 extravaganza – opening a gallery in 15 homes that will stay in situ until January. Here, it has a kindred spirit in the Langa Quarter – another shard of a happier tomorrow. While not strictly affiliated to the World Design Capital bonanza (it dates from 2010), it chimes in tune with plenty of the noble targets for 2014. This time, the nous behind the scheme is British – entrepreneur Tony Elvin – but the intention is similar: the positing of an unheralded area on to the map. The Quarter is an eight-street slice of Langa, abuzz with music, food and energy, which Elvin wants to push as a must-see corner of the city. "We are aiming for a situation where Capetonians, after they've had sundowners at Camps Bay, say 'Let's go and listen to some jazz in Langa'," he enthuses. He also imagines a "LAP" music festival that would unite Langa, Athlone and Pinelands just as racism kept them separate.

There are, of course, many positive flashes of unfettered 21st-century life in Cape Town that need no publicity drive: the merrily mundane scene that I witness at the revitalised Victoria & Alfred Waterfront, where the Rainbow Nation goes mall shopping amid all the screaming toddlers, bored teens and chain brands that characterise Saturday afternoon in any major city; the chic, inclusive crowd perusing the cocktail list at busy bar Tjing Tjing on Longmarket Street; the familiar Sunday swirl of families in the green lung of the Company's Garden – balls being kicked, bikes being ridden, ice creams being devoured.

Above this, laid out on a discreet slope, the Mount Nelson Hotel has observed many of Cape Town's dalliances with history. Nestled inside an early 19th-century mansion, it is named in honour not of Mandela, but of Horatio, and clings to a soft-focus take on British colonialism. Its Librisa spa deals stylishly in the now, but otherwise, the hotel pins itself to some vague year in the first half of the last century. In reception, framed posters pine for the antique ships of the Union-Castle Line, passengers on deck gazing cheerfully at a bright horizon. It is to be hoped that Cape Town foments similar confidence in its own future.

Getting there

British Airways (0844 493 0758; ba.com) flies to Cape Town 10 times a week from Heathrow. Connecting flights are available on South African Airways (0844 375 9680; flysaa.com) via Johannesburg.

Staying there

Belmond Mount Nelson Hotel, 76 Orange Street (0027 21 483 1000; mountnelson.co.za). Doubles from R3,960 (£234) including breakfast.

Cox & Kings (020 7873 5000; coxandkings.co.uk) offers three nights at the Mount Nelson Hotel, with flights, transfers and breakfast, from £1,345pp (two sharing).

Touring there

Coffeebeans Routes, 70 Wall Street (0027 21 424 3572; coffeebeansroutes.com). Half-day "Revolution Route" R995 (£56); half-day "Art Route" R695 (£39).

Visiting there

Langa Heritage Museum, Washington Street and Lerotholi Avenue (002721 694 8320). Daily 9am to 4pm except Sunday (closed).

More information

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks