Zambia: how the wildlife-rich nation has achieved a fall in poaching

Fifty years after independence, Zambia has much to celebrate

Through thorny scrub, we trekked for an hour with four armed rangers to reach the elephant carcass. Tinged orange from the soil, its bones lay scattered, dispersed by scavengers. The skull was heavy and huge, the size of a beach ball, but as if made of lead. Then began a detailed forensic analysis worthy of any crime scene. The shape of the skull proved the skeleton was female; her teeth indicated she was 27 years old; her decomposition suggested she'd died three years previously. But the clue to her death lay in her tusks. She had none.

Had poachers killed her, the tusks would have been brutally hacked off leaving gaping holes, but this elephant's tusks were naturally absent, as occurs sometimes in females. To be certain, a ranger swept the skeleton with a metal detector looking for bullets. Its silence confirmed she'd died of natural causes.

"Last year we had only five elephants poached in the Park, the lowest in our 20-year history," said Ian Stevenson. He is the chief executive of Conservation Lower Zambezi (CLZ).

This weekend, Zambia celebrates its 50th anniversary of independence. On 24 October 1964, the former protectorate of Northern Rhodesia became an independent republic within the Commonwealth. It has endured some economic and political turmoil over the half-century, and like other parts of sub-Saharan Africa has a tragically high rate of HIV and Aids. But compared with neighbouring Zimbabwe it is peaceful and politically stable. Almost one-third of the country is protected by National Parks and Game Management Areas. But conservation comes at a cost. Desperately underfunded, the Zambian Wildlife Authority (ZAWA) needs private donors and organisations such as CLZ for support.

Conservation Lower Zambezi is based near the western edge of the Lower Zambezi National Park. It assists ZAWA with logistics and in equipping, training and deploying its rangers. Data capture is critical to informing the frequent anti-poaching patrols that sweep the park and its buffer zone. Ian demonstrated a Google Earth map showing each of the rangers' routes; neon lines splayed across the screen like an elaborate Spirograph.

"We have an excellent relationship with ZAWA and the chief warden here, Solomon Chidunuka," Ian said. "That's crucial to our success." Also crucial are the 12 lodges within the park, which between them donate a quarter of the organisation's funding. It's a symbiotic relationship: without the wildlife, there would be no tourism, and vice versa. Both need each other.

But CLZ also needs local people onside or conservation will fail. With around 3,000 residents in the seven villages under the organisation's care and 2,200 elephants vying for the same space, their co-existence creates perpetual problems.

The crux of CLZ's community work is the Environmental Education Centre, where murals about conservation adorn the dorms and classrooms. "Getting the message across to the younger generation is vital," Besa Kaoma, the organisation's environmental educator explained. "They influence their parents, their own age group and their future children too." Pupils from 50 local schools come here for three-day courses on their natural heritage, visiting the park and the wildlife they'd previously only ever feared or fed on.

Many of CLZ's new village scouts first came here as schoolchildren. Last year, the organisation employed 20 scouts to work alongside ZAWA's rangers. From November to April, they act as a rapid response unit to deter marauding elephants from raiding crops in the fields and villages. Robert Phiri, a proud young scout dressed in camouflage, told me how he coped with the dangers involved. "When elephants charge, you must have courage" – he emphasised the word with a beaming smile. "You can't show you're afraid."

The education programme includes training teachers and scouts in conservation, assisting in guiding qualifications, helping women make handicrafts to generate income and developing a cultural centre for visitors. Perhaps the most important lesson, however, is teaching locals how to live with elephants rather than fight against them.

We drove to the riverside where women in colourful wrap-around skirts tended maize and sweet potatoes in the fields: a typical African scene, except for fences made of rags drenched in chilli-infused oil. Seemingly, elephants can't stand the piquant aroma of chillies, and CLZ has been spreading the word. "I saw elephants come towards my crops," one delighted farmer told me. "Then they smelled the chillies and just turned away!"

In villages, alongside traditional mud-and-thatch houses, we saw grain stores called felumbus, resembling giant old-fashioned beehives smothered with cement. Each holds a ton of maize. "Elephants can't smell the grain through the cement, so they walk straight past looking for food," Stephen Kalio, the organisation's human wildlife conflict co-ordinator explained. "Villagers make the bricks for the felumbu and CLZ provides the cement and expertise in building them." Lodges get involved too, providing used oil for chilli fences and facilitating guest donations for felumbus, it's a simple yet effective way of tourism that gives something tangible to local communities living alongside wildlife.

Lower Zambezi's wildlife is thriving: the elephant population is stabilising; this year for the first time, 20 sable were seen on the valley floor; eland and potentially rhino are to be reintroduced. CLZ plans another operations base at the park's eastern end, built by Anabezi Lodge which opened in April. On a patrol flight to Anabezi in CLZ's tiny Cessna, we saw no poachers. The beauty of the park unfurled beneath us as the Zambezi cut a swathe across the floodplains in a two-tone landscape of blue and green. Hippos looked like bloated pebbles in the river; rutting impala resembled prancing ants; elephants' tusks glistened like sabres in the sun.

With 11 huge suites overlooking the Zambezi and Mushika floodplains, Anabezi is the park's remotest lodge, and one of its most stylish. Our "tent" came complete with teak furniture, indoor and outdoor bathrooms, a relaxing lounge and a vast wooden deck with plunge pool and loungers on which to relax and watch the never-ending stream of impala, warthogs, elephants and baboons on the plain below. I took a morning walk with an armed ranger and Anabezi's manager/guide Matt Porter. We discovered leopard prints alongside the bloodied remains of an impala and watched six bull elephants, just 100 metres ahead, mooching silently to the river. On game drives, we saw kudu, fluffy waterbuck, mongoose, more elephants and hundreds of buffalo, while golden oriole, lilac-breasted rollers and parrot-like Lilian's lovebirds provided dramatic flashes of colour.

During our sunset cruise on the Zambezi, Matt gave a running commentary. A goliath heron about to fly was "all cinnamon and silver, taking off like a small Cessna." Nearby, a giant croc on a submerged sandbank looked "like he was walking on water" and elephants "transformed into ballerinas" as they waded into the river. On our last night, I woke to the sound of breaking branches outside our suite and could just make out the bulk of a bull elephant feasting on trees, leaving a trail of destruction. I watched in awe at his power and beauty, then thought of the scouts, and of the farmers with chilli fences and felumbus. Living with elephants isn't easy, but living without them would be tragic.

Getting there

Expert Africa (020 8232 9777; expertafrica.com) offers a week's trip to Zambia including five nights at Anabezi and overnight return flights from Heathrow to Zambia with South African Airways via Johannesburg for £3,668 per person, based on two sharing. It includes all transfers, domestic flights with Proflight, accommodation, park fees, activities, meals and most drinks.

More information

British travellers need a visa to visit Zambia. A single-entry visa costing $50 (£33) is available at the arrival airport or from the Zambia High Commission in London (zambiahc.org.uk; 020 7589 6655) for £35.

Zambia Tourism Board: zambiatourism.com

CLZ: conservationlowerzambezi.org

Bradt Zambia 5th Ed by Chris McIntyre

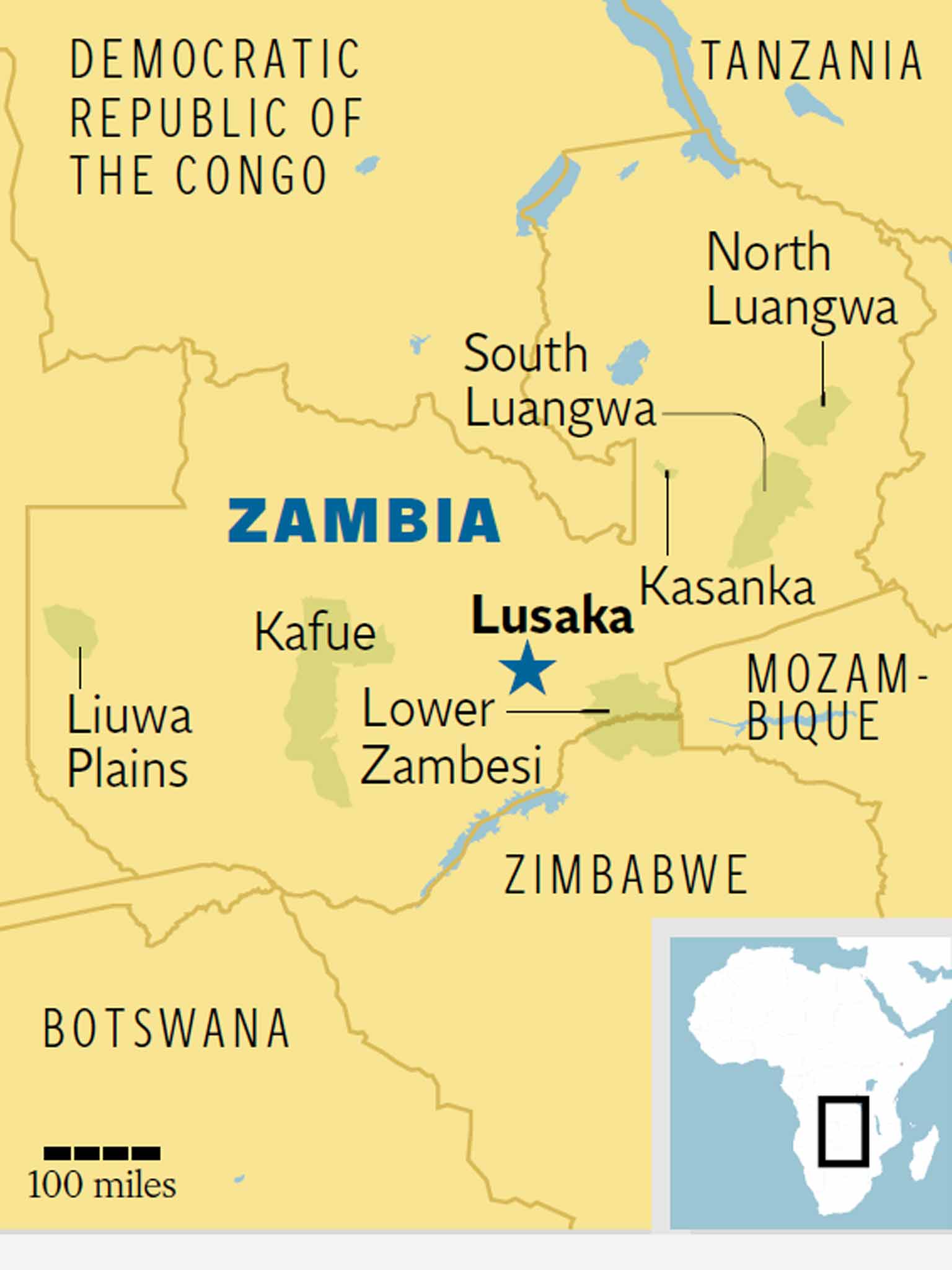

Zambia's top parks

KASANKA

Kasanka was Zambia's first park to be privately managed when, in 1990, a British expatriate and a local farmer offered to rehabilitate it through the Kasanka Trust. Big game is rare (elephants number around 40) but small animals and birds flourish. There's an incredible spectacle in November and December when millions of fruit bats swarm for food at sunset. The trust works with local communities and is funded mostly by tourism (kasanka.com).

LIUWA PLAIN

In the Lozi kingdom of Barotseland, Zambia's remotest and possibly most fascinating park was highlighted in a National Geographic film about its solitary lioness, Liuwa. Non-profit organisation African Parks assumed management in 2003 with ZAWA and the Barotse Royal Establishment, and wildlife now thrives: lions have been reintroduced and Africa's second largest wildebeest migration is here. There are no lodges, just a couple of campsites reached by mini-expeditions (african-parks.org).

KAFUE

The country's largest wilderness, Kafue is roughly the size of Wales and its diverse habitats host 158 mammal species and more than 500 species of bird, yet it sees relatively few visitors. Historically, the region suffered heavily from poaching but wildlife is vastly improving. In 2008, Game Rangers International was established to work with local communities; today its remit has expanded to elephant research, rescue and rehabilitation, and supporting ZAWA's rangers in conservation and anti-poaching activities (gamerangersinternational.org).

SOUTH LUANGWA

Zambia's flagship park (pictured above), where conservationist Norman Carr first developed walking safaris 60 years ago. It's still leading the field today with exceptionally knowledgeable guides, diverse wildlife and beautiful lodges. Created in 2003, South Luangwa Conservation Society supports ZAWA in law enforcement, rescue and rehabilitation of snared animals, and working with communities on alleviating human wildlife conflict (slcszambia.org).

NORTH LUANGWA

Neglected for years, it offers just three walking camps and very little infrastructure. Access is more restricted, evoking a true spirit of wilderness. For nearly 30 years, the Frankfurt Zoological Society has supported park management through the North Luangwa Conservation Project and between 2003-2010 successfully reintroduced black rhino, previously extinct in Zambia (zgf.de).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks