Zimbabwe: Bordering on the dangerous

Mike Unwin recalls a close shave with Botswanan customs officials in this extract from 'Irresponsible Traveller'

It's past midnight. My fellow passengers are sprawled across the hard benches of the railway carriage – some folded over luggage, others squash-faced against windows. Our train rumbles on into the night, eating up the dark miles of south-eastern Botswana. "Do it now." Louise hisses. I get to my feet and scan up and down the carriage. There's no sign of movement. The border guards are far behind us.

The aisle is an obstacle course. I manoeuvre over outstretched legs and hefty baggage to find myself standing between the closed doors of two toilets. Mine is the one to the left. I grasp the handle. But wait. Suppose they're watching me. One more step and the night will explode into lights, yells, whistles and uniforms. I ease down the window to let in a face-slap of cold air then, steeling myself to the task in hand, turn the handle and slip inside.

It's dark. The light fitting dangles bulb-less, but the moonlight is enough to work by. Lowering the toilet lid as noiselessly as I can, I climb up on top. There, high on the outer wall, is the hatch – closed, just as I'd left it three hours earlier.

Behind the small, hinged door is a recess through which the guard inserts the train's destination sign. That's not what I'm interested in, though. On a narrow shelf behind the door sits a fat wad of cash: pounds sterling, US dollars and Zimbabwe dollars. I know, because I put it there. And now I've come to take it back. But there's a problem. The hatch is shut tight. I run my fingers around the frame, searching for a fingertip grip with which to prise it open. No joy. Now I can make out the small metal keyhole. Locked. But it hadn't been locked earlier. The catch must have engaged when I closed it. My heart sinks: I now recall a distinct click.

I should explain how I got to this point: I'm not a habitual smuggler. In fact, I like to think I'm not really a criminal at all. This incident took place in April 1989. I was newly arrived in Zimbabwe – just 10 years independent back then, and widely celebrated as an African success story.

To me, fresh out of university, the country seemed ripe with opportunity and adventure. The trouble was, without my own wheels its wildest corners were out of reach. And cars in 1989 Zimbabwe were like gold dust. Trade restrictions with then-apartheid era South Africa meant no new vehicles, while any second-hand jalopy that went for sale, however decrepit, was snapped up pronto.

Botswana was the answer. Zimbabwe's neighbour had no ethical qualms about trading with the evil regime, and its garage forecourts were said to glitter with second-hand vehicles direct from Pretoria.

The problem was how to pay for the car. Without credit cards, this meant cash, and the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe set a miserly single-trip export limit of Z$400 (then about £75). Banks would not issue foreign currency, and my precious supply of sterling had already dwindled to a pittance. So, taking advice, we begged, borrowed and scraped together all the cash we could. The plan was to declare what we could legally export and smuggle the rest over the border by train.

Soon after departure, the industrial suburbs gave way to the arid bush of Matabeleland. The carriage was packed. Bags were jammed into overhead racks and wedged between knees and ankles, many containing goods that owners hoped to sell in Botswana if they could get them over the border.

Dusk was falling by the time we reached the border at Plumtree, some 100km south-west of Bulawayo. As soon as the train had hissed to a halt, I craned out to survey the platform. Sure enough, a phalanx of starched uniforms and peaked caps was mounting the first carriage. The guards would work their way up the train, checking papers, stamping passports, collecting customs slips and searching anybody whose "nothing to declare" didn't quite ring true.

A knot of fear tightened in my stomach. What had I been thinking? Of course they'd search me. We were the only white faces, smuggling ganja, probably. I began shouldering my way down the aisle to the toilets. The door on the right was locked. But the one on the left gave way and I stumbled inside, closing it behind me. Heart pounding, I cast around my squalid little cell for a solution. Flush the money down the bowl? Cut it up and swallow it?

Then I spied the hatch. It swung open to my trembling fingers. Eureka! With no time to lose, I started emptying my underwear. In seconds flat I had stuffed the cash into the hatch and was returning to my seat. We handed over our less-than-honest customs declarations for the polite, smiling officials. Once the last guard had disembarked, we pulled away into the night with a collective sigh of relief. As soon as the carriage had nodded off I would collect my stash. But as the rustling turned to snoring, so my fears returned. What if the officers' smiles had been a charade? What if they'd found my money and were now hiding – perhaps in plain clothes – waiting to nab me when I returned to the scene of my crime?

So now I'm staring at the locked hatch, racked with doubt. What happens to currency smugglers in a Zimbabwe jail? I creep back to break the bad news to Louise. "What do you mean, you didn't get it?" she hisses. I daren't meet her eye but lever my backpack down from the luggage rack and fish through the outer pockets in search of something – anything – that might rescue me. Bird book, insect spray, playing cards, Swiss Army knife. Bingo! Clutching my trusty weapon, I return to the loo.

It takes 10 minutes of grunting, swearing, twisting, chiselling and splitting before – bleeding from a gashed thumb – I've inflicted sufficient damage on the lock for the door to flop open. And there's my cash. All bundled up in plastic bands, just how I left it. I fish out the grubby wads and stuff them back down my pants. Then, heart in mouth, I open the toilet door and step out into the corridor.

There's nobody there. Nobody to bludgeon me senseless, clap me in irons and drag me away: just the reassuring rhythm of the train on the tracks and its snoring passengers. I'm shaking with relief and adrenalin. I strut back down the carriage with all the swagger of a man who knows he carries in his capacious underpants a shiny second-hand Mazda 323 – or at least the cash equivalent. I'm a travel-hardened criminal and Africa is my oyster.

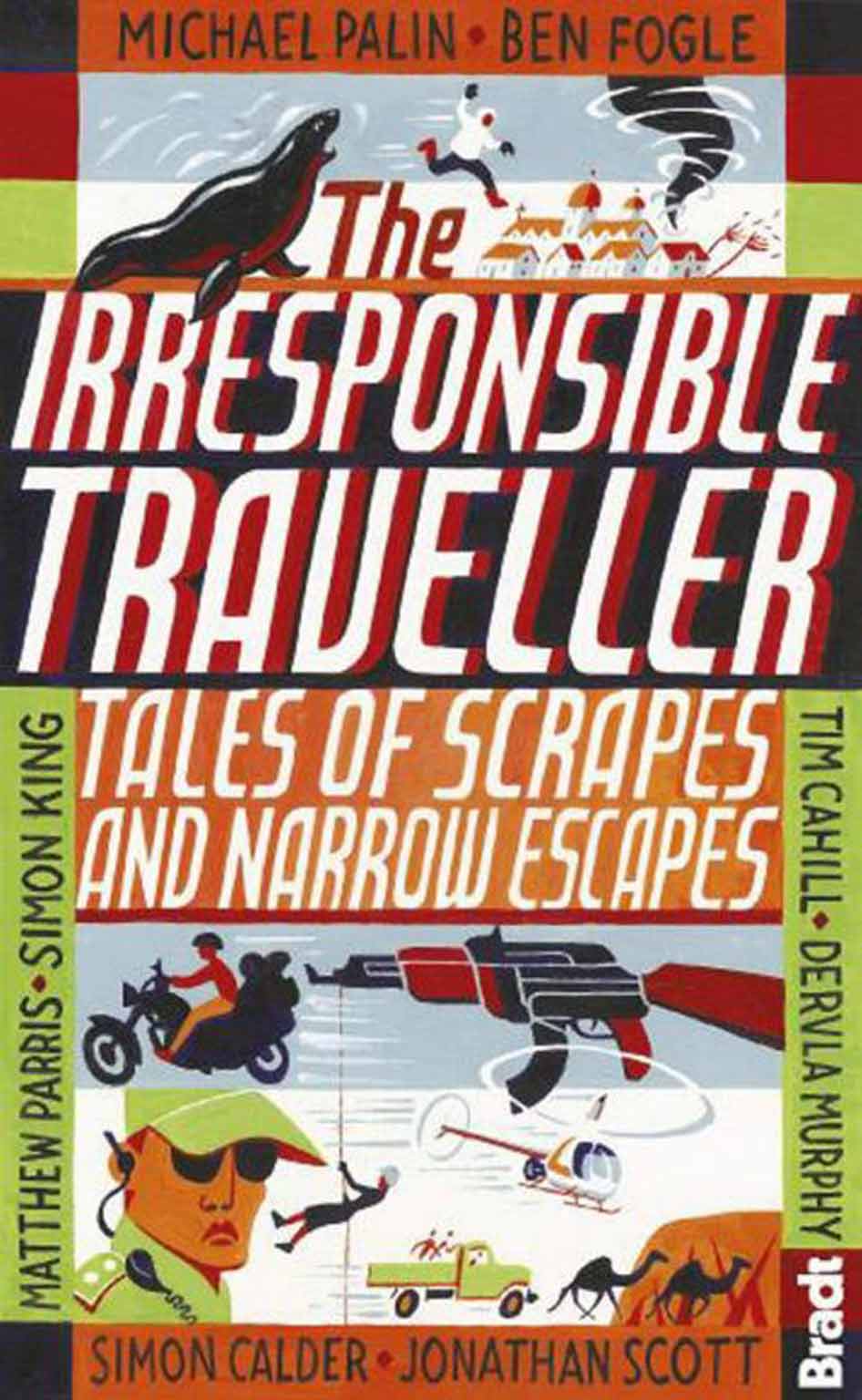

This is an edited extract from Irresponsible Traveller, compiled and edited by Jennifer Barclay and Adrian Phillips (Bradt Travel Guides; £10.99). For a 50 per cent discount, enter the code INDEPENDENT at checkout on the Bradt website. Find out more at the Irresponsible Traveller event on 1 October at the Royal Geographical Society, London (bradtguides.com).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks