The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Meet the heroes fighting to put a stop to the cruel practice of elephant riding

In Laos, ‘the land of a million elephants’, you can stay at an elephant hospital to learn why it’s high time tourists stopped riding them

Standing in the skirts of the jungle, the whimsical turquoise cascades of Laos’ most noted waterfall, Tad Sae, rolling down the mountain beside me, I feel like I could be in a Bounty advert. The soundtrack is that of insects chattering urgently. Sadly, the sight of four elephants pacing about on short chains, with howdahs (chairs) strapped to their backs, puts a dampener on things.

“How many times,” I ask the man who sells rides on them, “will they go up and down the hill today?” “Twenty-five!” he answers enthusiastically. A fully grown elephant can carry up to 150 kilograms on its back, but when you consider the weight of two people (around 150 kilograms), plus the howdah (weighing around 100 kilograms), and also the mahout (who rides on the neck), it all adds up to double the amount these creatures can safely support.

And unbeknown to many well-meaning travellers, giving rides is actually painful to an elephant, for their spines are jagged. Often the chairs are left on their backs between rides, causing sores, while the animals lack sufficient protection from sunlight and have no social time to be elephants, nor the time to snack throughout the day to sustain their immense frames. Disturbing stories have peppered international newspapers lately of tourist elephants being forced to work oppressively long hours in burning heat without respite or hydration.

In Luang Prabang, one of the most enchanting cities in the Far East, there are a plethora of elephant camps where you can variously ride and bathe them. Sadly, of all these only Elephant Village has forbidden the howdah and admits one traveller at a time to sit on the elephant’s neck – the only place the animal can comfortably support you. The argument goes that to deter people completely from elephant riding would mean a lot of elephants suddenly had no work and would be destroyed.

Fortunately, there’s a magical place where “elephants are allowed be elephants”, where tourists are forbidden to ride on their backs, and the animals are given back their freedom in an idyllic area beside a lake. Set up in 2011, the Elephant Conservation Centre in Sainyabuli, an easy two-hour trip by car from Luang Prabang, has become the most talked-about attraction in Laos; and this in a country that has more than its fair share of subterranean river rides, fantastical caves, zip lines and national parks. Mahouts (the owners) and their elephants are paid a fair salary to come and live here for up to four years while their cows get to rest, are fed and watered and receive full medical care – and, most importantly, have the chance to bear young.

This is crucial because, for every 10 elephants that die in Laos, only two are born. A massively depleted population of around 850 wild and domestic elephants now remains in a country once called “The Land of A Million Elephants.” Part of the reason is because mahouts can’t afford to give them time off logging or tourism in order to mate and raise a calf; with four years’ gestation, lactation and education. Approaching the Conservation Centre, our group’s boat putters amiably across a placid green lake. The peace is broken, however, when a huge head breaks the surface of the water like an ascendant Kraken, trumpeting our arrival in a spray of water. My stomach performs an involuntary cartwheel.

Once moored at the jetty, we dump our bags in our basic-but-spotless bamboo bungalows, then head down to watch the elephants bathing. Yet more pachyderms are clustered in the water, their eyes a bright hazel, their skin a bristly spectrum of greys and browns. One of the females is a little aloof and bathes alone; another keeps a safe distance while trying to make her feel welcome; one doesn’t like kids; another loves people. We quickly learn these gentle giants have very different personalities and fears, and get the chance to feed them shoots of bamboo. Many are ex-logging elephants that had been on the point of collapse (the centre also teaches mahouts to transfer their skills to elephant riding rather than logging).

We head over to the Centre’s hospital and watch as Annabel Lopez Perez, the resident vet and biologist, performs a check-up in the “medical crush”, a giant wooden frame that secures the elephant. While a mahout distracts the cow with target training – a method whereby the animal is encouraged to perform a task through positive reinforcement and is rewarded with treats – Annabel checks her toenails and teeth, all the while cooing softly as if the huge beast is one of her babies.

Later, as the crickets begin their evening chorus and the sunset drips orange into the lake, we meet in the restaurant for a communal dinner. “Currently there are no official government guidelines to enforce acceptable standards for elephants; be it their living conditions, diet or hours,” Annabel tells me. “This allows camps the opportunity to overwork them.” Long-lashed and raven haired, with her good looks and fiery conviction, she reminds me of Brigitte Bardot and her dogs, or Diane Fossey and her apes.

“How many hours should an elephant work per day?” I ask her. “Three one-hour treks, avoiding the strong heat in the middle of the day,” she answers. I think back to the hellish treadmill of 10-hour days in the camps of Luang Prabang. It’s as if the lucky few who come here have won the lottery.

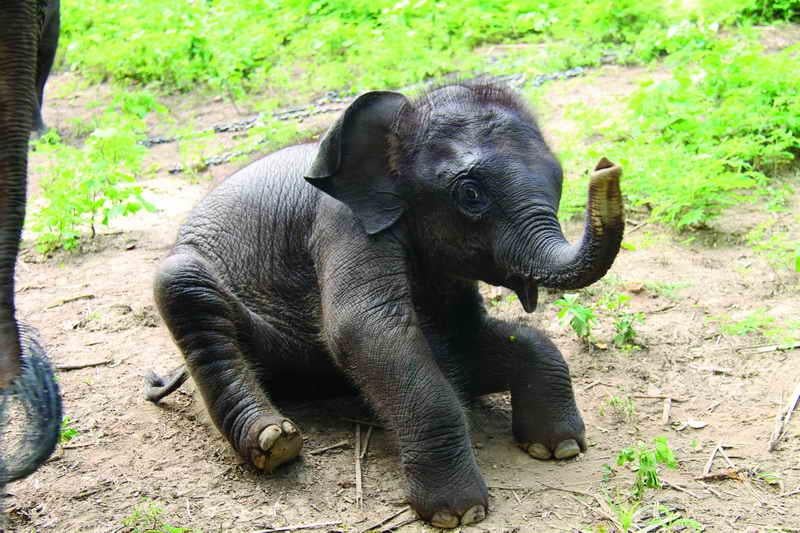

Over the next three days, we watch the elephants from high towers in the socialisation area, where they learn to re-herd and form relationships after lonely existences in logging or tourism. We also see them solve puzzles in the play area (such as sniffing out cunningly hidden food) and bathe with their young. At one point a bird caws and the littlest calf, Suriya – hairy, cute and gangly as a Kipling character – squeaks in fear. Soundlessly the females move around him offering comfort, their quiet compassion touching. “We’re not here to stop people riding at the camps, that’s not realistic, but we want to help them improve standards, like less working hours and the chance to breed,” Annabel says. “Elephants are not toys.”

Returning to Luang Prabang thoroughly enchanted by my time here, I’ve seen the only way to really interact with an elephant – on their terms, not ours.

Travel essentials

Getting there

Singapore Airlines (singaporeair.com) and its regional wing SilkAir fly three times weekly to both Vientiane and Luang Prabang from Heathrow. Return fares start at £850.

Staying there

Three-day, two-night stays at the Elephant Conservation Centre (elephantconservationcenter.com), including accommodation, meals and return transfer by boat and car from Luang Prabang, are advertised at US$265.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks