Great Barrier Reef: Reports of its demise have been exaggerated, claim locals

Look beyond the headlines and you'll find the Great Barrier Reef still has life in it, says Jenny Peters, who's just back from a visit

Despite reports to the contrary, the Great Barrier Reef really is not dead yet. Last week, Unesco resolved not to add it to its “endangered” list, notwithstanding fears that it would (and even with surprising additions such as Vienna). And in fact, as travellers who still have not ticked it off their bucket list will be happy to hear, locals on the ground say that there is plenty of life left in the world's largest barrier reef.

That is notwithstanding the back-to-back bleaching events that occurred along the reef in 2016 and 2017, in which the waters that envelope this natural wonder not only overheated but stayed hot through winter, effectively stopping the coral from spawning (which is how it reproduces and thrives). Adding in the effects of Cyclone Debbie, which made landfall in the Whitsunday Islands and at Airlie Beach in March this year, and there is no doubt that the reef has been taking a battering lately.

“To be honest, we're in uncharted waters,” says Doug Baird, a marine biologist and the environment and compliance manager for the Quicksilver Group, Australia's largest Great Barrier Reef cruise company. We’re sitting together on the Cairns Esplanade, one of the main jumping-off points for tourists to visit the reef.

“What we’re seeing here is the effect of back-to-back bleaching events,” he says. “But I believe it is not quite as bad as people have been saying. Remember, when you are talking about something as large as the Great Barrier Reef, you are talking about something bigger than the United Kingdom.”

In fact, the Unesco World Heritage-designated Great Barrier Reef Marine Park – which supports about 40,000 jobs in the region – stretches 1,430 miles, extending south from the northeastern tip of Queensland down to just north of Bundaberg. It includes 3,000 coral reefs, 600 continental islands, 300 coral cays, 1,625 types of fish and much more. Its sheer vastness is one of the reasons Baird insists the reef is hanging tough, despite the well-publicised hits it has recently taken.

“We find there are quite large differences between individual reefs — even in different zones of the same reef,” he says. “You can jump in in one place and see quite a lot of evidence of bleaching. Then you can swim 50m either way and get into a patch of reef where there’s really no evidence of bleaching at all. So the effects are really patchy on an individual basis. Unless you’re actually looking at every single reef, there’s going to be an element of generalisation.”

Ben Hales, captain of the Reef Encounter, a luxury mini cruise ship, agrees. “There has been a noticeable effect of coral bleaching in the last two years,” he says. “But around the part of the reef we visit, they said 92 per cent is dead, and that is simply not true. It is bouncing back.”

Hales helms his 42-passenger ship around the major dive and snorkelling reef sites of Norman, Saxon and Hastings — all located in the Coral Sea on the outer edge of the continental shelf between Cairns and Port Douglas.

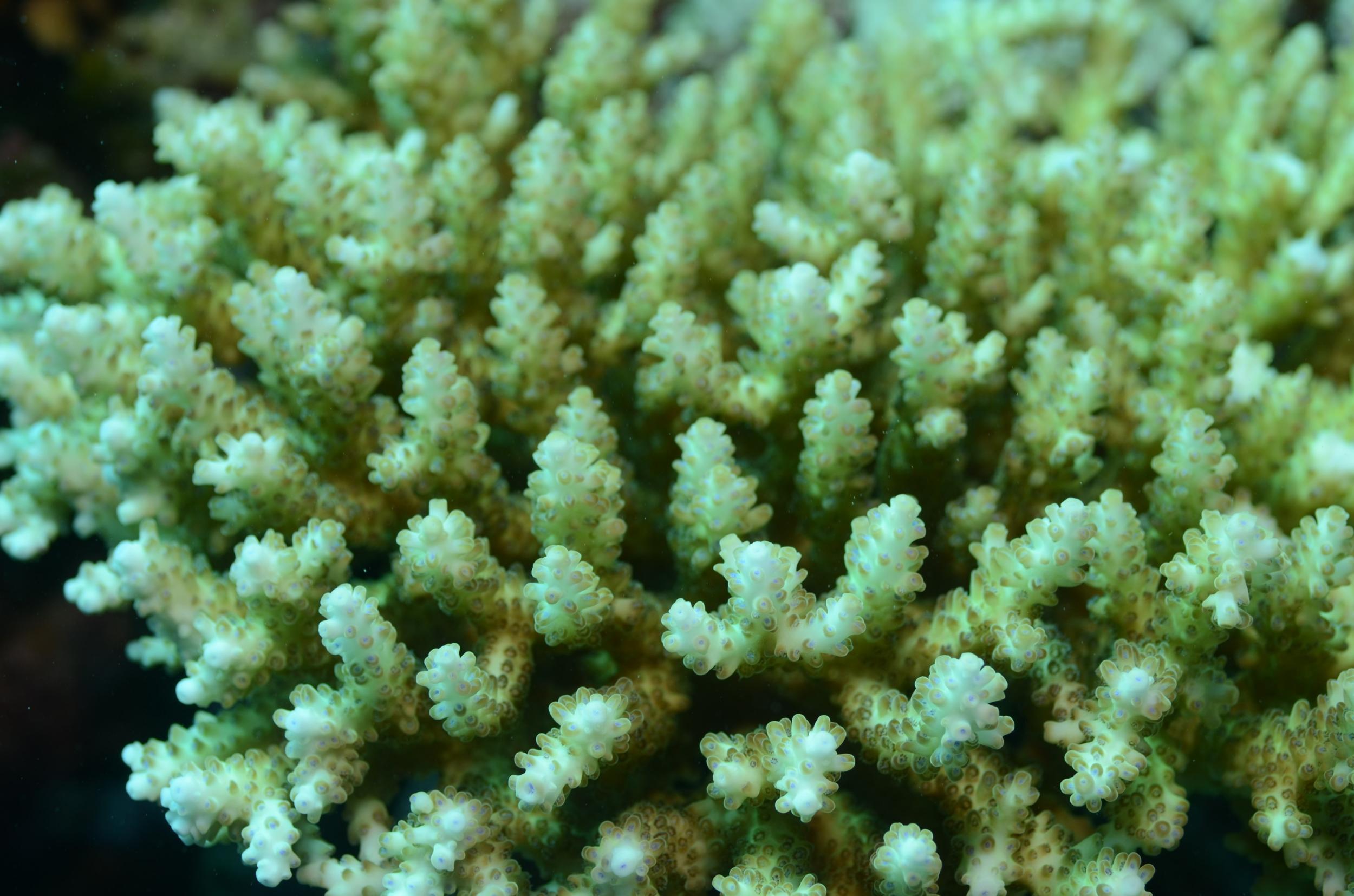

After spending three days on board, scuba diving at all of those sites (which I’ve visited several times in the last 20 years), I saw a mix of thriving corals and woefully bleached ones — a new sight for me, each colourless section telling the story of its recent history.

But it is not all doom and gloom. I also saw plenty of marine life: tropical fish, sea turtles, sharks, rays and other underwater creatures. And Jenny Cheetham — the ship's purser and onboard marine biologist — thinks the reef has not yet reached the point of no return.

“The coral can recover, it can survive,” she says. “But I think there needs to be a global-scale cleanup. And I think it has to come from a higher level, from the government, to really make a lasting change.

“There are many factors, including global warming, the increase of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere (which goes into the oceans) and the ocean acidification from things like farming nearby, where the fertiliser goes into the water.”

Annastacia Palaszczuk, Queensland’s premier, promises the regional authorities are on the case. Her government has allocated A$1.1 billion (nearly £650m) to help with the repair. She is also spearheading a state shift to renewable energy sources — authorities hope to meet a 50 per cent target by 2030, investing more than A$2 billion (more than £1.1bn).

But she says it is not just up to them. “Everyone has to play their part. We are part of a world community and the Great Barrier Reef is not just a national icon; it is an international icon that must be protected.”

According to the Great Barrier Reef Foundation, some of the key initiatives of the 24 important research studies currently funded and being conducted include creating an “early warning stress test” for coral reefs, which alerts scientists to problems on a reef before any physical signs are visible; developing a “sunscreen” for the reef using biodegradable surface films to stop damaging heat and light from penetrating the water over the corals; and studying the genomes of Red Sea corals to understand why they survive and thrive at higher water temperatures than those at the Great Barrier Reef.

The idea of protecting and helping the reef to survive is a relatively new one, Baird explains. “Up until now the marine park authority and scientists tended to look at the reef as something that could look after itself,” he says. “The thinking was that it is big enough, the sheer scale would keep it resilient and robust enough to bounce back.

“But now we know it needs help to survive. The good news is that there is work going on looking at how we can help the reef, and a lot of people now believe that we need intervention strategies to try to help the reef. So a lot of what is happening now is what we call ‘assisted evolution’ – looking at strategies for restoration and repair, rather than just managing the marine park.”

So in short, there is still hope. And as for that bucket list, should the Great Barrier Reef still be on it?

”There is a lot of life out there!” says Ben Hales. Doug Baird agrees.

“The Great Barrier Reef is one of the most stunning experiences in the world,” he says. “There are still beautiful areas out there. And once people come here, we try to give them the facts and information about it all — what's causing the problems, what we’re doing to solve them and the fact that they can actually make a difference themselves.

“It can often overwhelm you, this whole idea of climate change. But if everyone tried to reduce their carbon footprint, the sheer physics of scale would make a difference to the Great Barrier Reef and beyond.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks