The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Puglia: not down at heel, just rugged good looks

Puglia might not have the polish of the Amalfi coast or the elegance of Tuscany, but therein lie its charms, as Chris Leadbeater discovered on an early autumn visit

The Corner Ristorante does not look promising. With its drab brown concrete walls, each of them bereft of windows, it seems the sort of establishment where you might encounter dirty beer glasses and broken pool cues, angry glares and the unspoken threat of violence.

But we are tired and hungry – "fresh" off a plane into Bari, and assessing our options at this late hour in the city's unremarkable suburb of Palese. They are not plentiful. I glance again at the grubby framed menu attached to the lintel – and push tentatively at the door.

We tumble into a tomato-sauce advert. Inside, families of all ages are dining with Italian gusto: babies smiling; mothers clucking; children pushing portions of pasta around plates that are too big for them; groups of men in intense conversation. The smell coming from the kitchen is heady and rich. Ten minutes later, as our antipasti appear, my wife raises an eyebrow and a fork heavy with mozzarella, and declares: "This is better than I expected."

This unfussy neighbourhood eatery could be a symbol of the region in which it sits. The most south-easterly nugget of the country, Puglia is – famously – the heel of the Italian geographical boot. Like most heels, it is scuffed and scratched, worn down by the tread of daily existence. Here is a distant agricultural cousin of the dilettantes of Milan and Rome, filled out by farmland and shaped by the seas that gnaw insistently at its limestone sides – the Adriatic to the east, the Ionian to the south, the Gulf of Taranto to the west. It is unglamorous, under-appreciated, flinty and awkward. Yet peer within, and you glimpse an example of Italy at its purest – rural and unhurried, a place of small towns and a life quite ordinary, where citrus trees sway in the breeze and days drift by in silent sunshine.

Such a scenario is exactly what we are seeking as summer slides into autumn – though we do not find this desired tranquillity in Bari. The Puglian capital is noisily Italian, right down to the traffic that clogs its veins. There is beauty, however, amid the chaos – the 12th-century Cattedrale di San Sabino, calm incarnate as it rears over Piazza dell'Odegitria; the more diminutive church of San Gaetano, concealed down the alley of Strada San Gaetano, where washing hangs from balconies; the thick flanks of the (largely) 13th-century castle, still guarding the city.

We sip coffee in the shadow of the latter, preparing for a drive south-east that will take us on to the Salento peninsula – the lower tip of the region. First, however, we must delve into the rust and dust that wells up immediately below Bari – factories perspiring on the lip of the Adriatic; numerous shipping containers lined up at the port, a vast metal jigsaw. This industrial zone stays with us doggedly, past Monopoli, and on to Brindisi, where ferries chug across to Greece.

And then, somewhere near the village of Torchiarolo, the mood changes. The SS613 has discreetly abandoned the sea, and on each side of the road, the landscape has peeled back to reveal rustic Italy, the occasional vineyard ebbing away in furrows. Lecce provides an urban interruption, but in fine fashion, the Piazza Sant'Oronzo still cradling a Roman amphitheatre. Beyond, the SS101 completes the transition, funnelling us to the lower edge of Salento, where Gallipoli is a seafront flurry of fishing boats and fruit stalls – patched-up hulls and boxes of tomatoes jostling for space alongside the Gulf of Taranto.

Attention, though is diverted. Some 700 miles to the north, Juventus are playing football in Turin, and Gallipoli is transfixed. In the streets behind the castle, commentary seeps from doorways. In one location, a man watches through the window of a friend's house, chair planted on the pavement. It is a rare example of Puglia turning its weathered face to the rest of Italy. We will not come across many more.

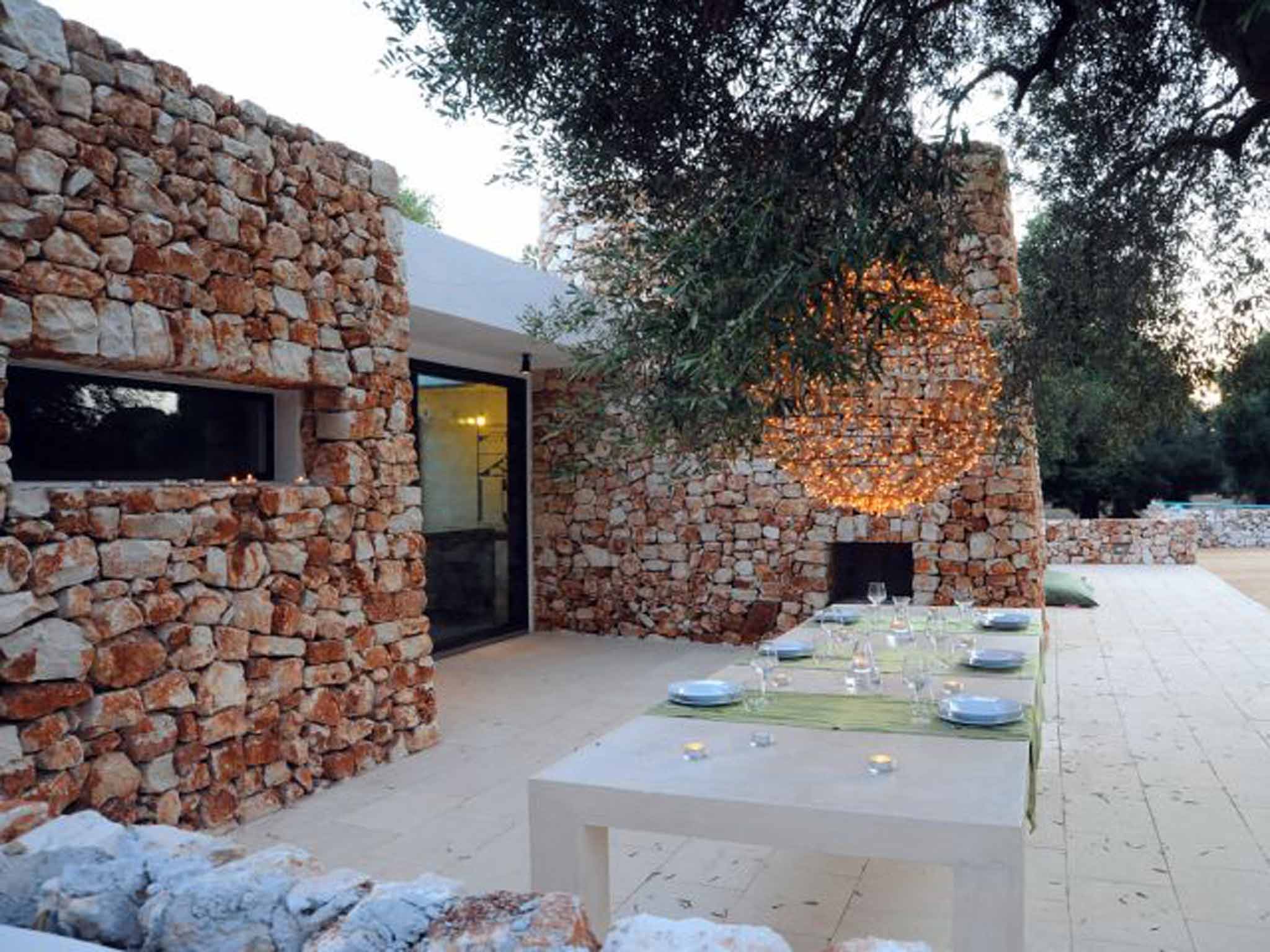

Our destination is a further 25 miles south, and it gazes not at Piedmont, but at the water. Almost. A retreat from the world, Bosco degli Ulivi is tucked two miles inland, nearly at the tip of the peninsula, just above the "town" of Torre Vado. Indeed, it is so well hidden that, initially, we struggle to find it, re-tracing the same spiderweb lanes until we stumble upon the driveway. As its name suggests, it lies in an olive grove, though the first sign of its presence is a flash of afternoon light on its windows. A three-bedroom property, it is a cocktail of modern and traditional. The villa is boldly 21st century: cement floors and hard counters in the open kitchen; white linen on the beds; a swimming pool outside. But the loamy red soil under the trees is classically Puglian. At the rear of the garden, a pajara – a squat stone storage structure of indeterminable age – lingers, its interior coolness still infused with the tang of animal fur and damp straw.

And so we switch between the villa and Torre Vado – where the titular 16th-century tower continues to watch for invaders. Families dot the beach in parasol clusters as, adjacent, unpretentious eatery La Kambusa doles out more pizza-based nutrition for hungry bambini.

On our third evening, we return to Bosco degli Ulivi knowing that we have help. Think Puglia, the agency through which we have rented the property, offers an in-villa dining service. Gina Vesuvio sweeps in, ushers us away with the unquestionable authority of a kitchen matriarch, and prepares a feast. There are plates of prosciutto and heaped bowls of big-eared orecchiette pasta with lumps of turnip; strips of pork marinated sharply in lemon juice, and a fruit salad of local peaches and plums. We have little in the way of shared vocabulary, but the meal needs no translation. At the end of the night, she nods curtly and departs, leaving us to contemplate our bulging stomachs.

It would be easy, in the wake of this, to snooze like pythons in a digestive daze for the rest of the week. But this is a region that, for all its earthiness, demands exploration.

The plan, on the brightest of Tuesdays, is to forge anti-clockwise along the shore. Below Torre Vado, Santa Maria di Leuca protects the corner of the peninsula, its lighthouse monitoring the spot where the Gulf and the Ionian confer. On this morning, their meeting is almost polite – gentle surface ripples, small boats bobbing in a search for squid.

But beyond this point, a salty toughness makes itself felt. The coast, as we cut north, is a spartan mix of bare rock and spiky cacti. At Il Ciolo, a gorge forces its way to the sea, water frothing urgently within. Castro is another defender, its 12th-century castle glaring at the road. And if the gilded resort of Santa Cesarea Terme softens the situation with its gelaterias and holiday homes, Capo d'Otranto reasserts the idea of rough and rugged, Italy's most easterly extremity thrusting its elbow into the confluence of the Adriatic and the Ionian. Forty miles away, Albania broods in the haze.

We meander on, into the town of Otranto, which succinctly unites this clash of styles. Its medieval walls are high, sturdy, and foreboding. But the aroma of grilled swordfish that emanates from La Bella Idrusa, a restaurant on the quayside, insists that we sit and eat.

We return to the villa, rest, then – two days later – go again, this time up the west edge of the peninsula, back to Gallipoli and on into the idyllic enclave of Santa Maria al Bagno, as it clings to its natural harbour. Perched on the sheltered waters of the Gulf, this side of Salento lacks the cragginess of its eastern counterpart. The tiny port of Santa Caterina sits bathed in sea-sparkle, while Torre Squillace poses on a splendid crescent of yellow sand.

Our final halt is at Porto Cesareo, where a thin causeway crosses over to the island of Lo Scoglio. Here, Ristorante Lo Scoglio dispenses a serious version of Italian cuisine. There are cashmere sweaters around shoulders, studious frowns for the benefit of the wine list, and the refined clicks of cutlery on crockery – on a veranda in sight of another blocky watchtower. For all this, the house risotto is gloriously simple, a fleet of prawns lost in sticky rice. Somehow, the clock accelerates, and as we drive back to Torre Vado, we are granted the sort of sunset that dares you not to pull over and stare.

Perhaps the small hand continues its breathless sprint, because the weekend dawns with unappreciated speed. But the joy of the region is that even the trundle back to the airport throws out slivers of the wonderfully picturesque.

Ostuni decorates its hilltop like birthday-cake icing, its buildings starkly whitewashed. Then comes Alberobello, the engaging oddity whose celebrated trulli – conical houses that taper upwards, pushing architectural snouts into the sky – have garnered it Unesco World Heritage status. Suddenly there are tour buses and exhaust fumes. But even amid a forest of out-stretched camera-phones, it is clear that Unesco's global rubber-stamp is as close as Puglia comes to shouting about its charms. And as we nibble at gelati from Bar Pasticceria del Corso, we marvel that, in a country known for the quality of its shoes, even the heel can be endlessly pretty.

Getting there

EasyJet (0330 365 5000; easyjet.com) flies to Bari from Gatwick; British Airways (0844 493 0787; ba.com) flies the same route until November. Ryanair (0871 246 0000; ryanair.com) flies to Bari and Brindisi from Stansted.

Staying there

Bosco degli Ulivi sleeps up to six, and is available from £2,483 per week in September and October, through Think Puglia (020 7377 8518; thethinkingtraveller.com). In-villa dining is €80 (£63) for two-three people, €120 (£95) for groups of four-seven (plus cost of ingredients).

More information

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks