21 years of air passengers’ rights – Simon Calder asks: has it worked?

‘261 is a legislative mess that damages the interests of passengers’

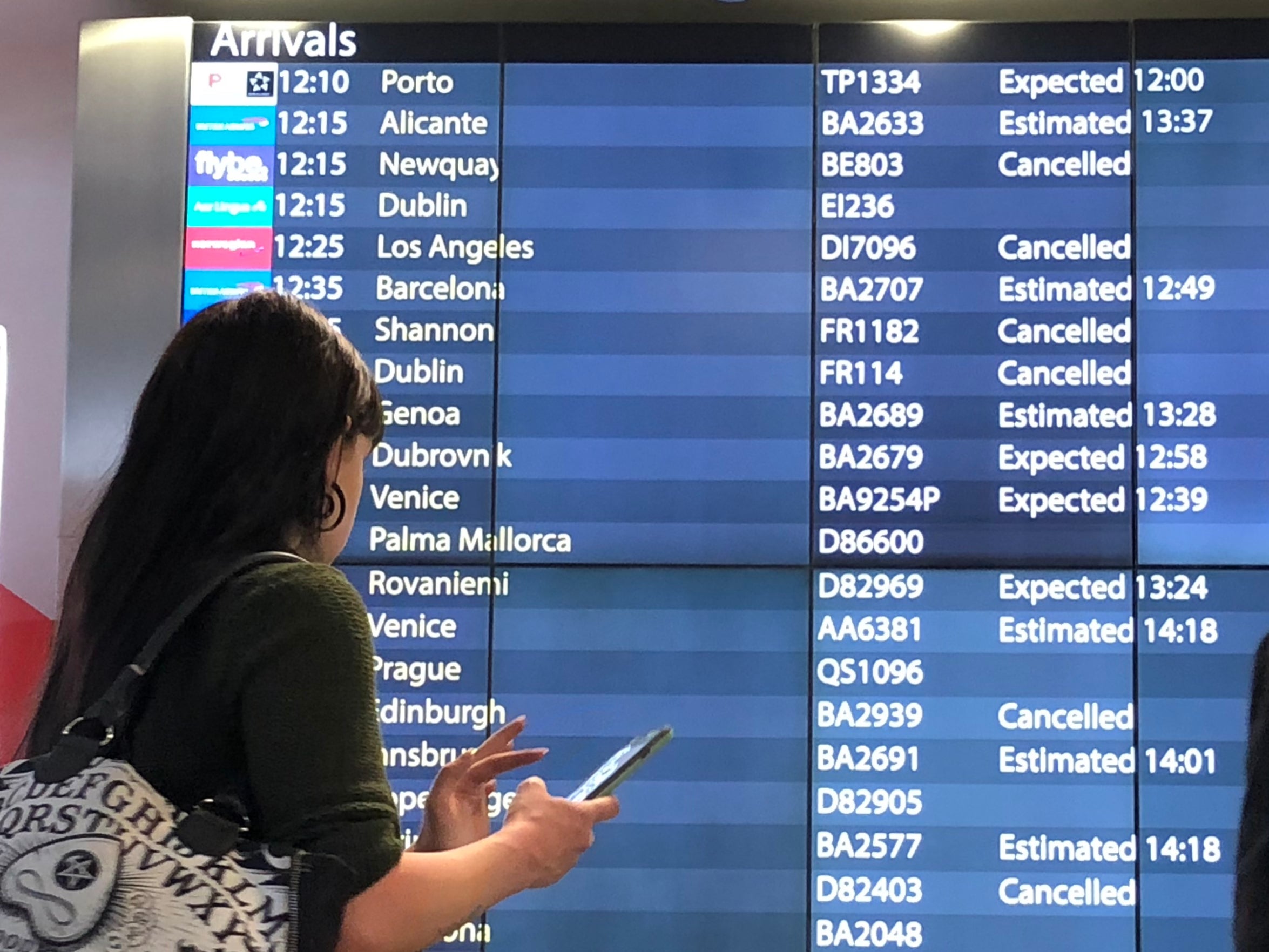

Early one Wednesday morning in July 2019, a tragedy unfolded at a Stuttgart airport hotel. The first officer who was due to fly the morning’s TAP Portugal flight to Lisbon was found dead in his bed.

The rest of the crew, who had flown from the Portuguese capital with their colleague the previous day, were understandably distraught. The airline flew out a replacement crew and the flight departed 10 hours behind schedule.

Almost four years later, the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg ruled that TAP Portugal must pay €350 in cash compensation to passengers who had claimed for the delay.

The case had been brought by a claims-handling company. The legal profession is the one constituency to have thrived from Regulation EC261/2004 since it took effect 21 years ago. Individual passengers, including those who were delayed by the passing of the pilot, have also benefited. But overall, air passengers’ rights rules comprise an unholy mess that damage the interests of travellers and persuade some airlines to act in ways that go against the principles of decent customer service.

The aim of the European parliamentarians was reasonable: to require airlines to provide care for passengers whose flights were disrupted, and to pay cash compensation when their failures caused cancellations or in cases of overbooking. But a series of court judgments has created case law with unforeseen consequences that are not in the best interests of travellers.

These are the detrimental effects.

Compensation scales are nuts

European judges ruled that a three-hour delay is equivalent to a flight cancellation – or, indeed, a 30-hour delay. Passengers on the shortest flights (anything up to 1,500km) get €250, while those whose journeys are between 1,500 and 3,500km earn €400. Bizarrely, while a few hours’ delay on an intercontinental flight is probably less of a pain than the same tardiness on a weekend break to Barcelona, the payment is a stonking €600 – though that amount is halved if the delay is between three and four hours.

Bureaucrats have been paid for coming up with this nonsense.

There is no relationship between the fare the passenger paid and the amount of compensation, which helps to explain why …

Airlines are incentivised to obfuscate

Consider a flight from London to Sharm El Sheikh in Egypt with 235 passengers booked in either direction. A four-hour delay that is the airline’s fault triggers potential claims of almost a quarter-of-a-million pounds. Were I (heaven forbid) to be running an airline, I would be tempted to:

Make it difficult for passengers to understand their rights, for example by requiring them to click on a link in an email rather than explaining the airline’s obligation in plain English.

Come up with possibly fatuous reasons why “extraordinary circumstances” caused the delay, because that absolves the airline of paying out cash. The worst that can happen? Some passengers will persevere and win a payout but many will be deterred.

Unsurprisingly, a lot of airlines seem to behave like this; Tui is a notable exception, being upfront when its shortcomings trigger a long delay.

More passengers are delayed, rather than fewer

Flightradar24 is an excellent resource. At the start of the day, the flight tracking service can indicate the actual aircraft to be used for a particular flight. Yesterday, for example, the easyJet A319 known as G-EZBX had a busy day shuttling from Glasgow to Luton for a series of round-trips to Amsterdam, Geneva and Belfast – all of them nicely on time.

If you have a flight later in the afternoon – as I did one day from Tirana to Beauvais – you can track your intended plane’s progress. I headed for the airport in the Albanian capital, happy that the Wizz Air jet was on schedule. But by the time I arrived at Mother Teresa International, the plane had been assigned to a different route – and mine was now running late.

It appeared that the airline had an aircraft that had “gone tech” in Poland. In order to keep all delays below three hours, the fleet was shuffled. My flight, and several others that were originally on time, was rescheduled and finally arrived 90 minutes late. But by rationally ensuring no single flight exceeded the arbitrary three-hour delay mark, the carrier could avoid claims totalling perhaps €100,000.

The rules are ridiculously lopsided

Passengers’ rights legislation applies to all flights on British and EU airlines – and to non-European carriers on departure from airports in the UK and EU. That leaves a significant gap: non-European airlines flying from outside Europe are not covered. So when Qatar Airways cancelled my Kathmandu-Doha-London booking, there was no obligation to find an alternative option. I was left £1,000 out of pocket after I flew via Bangkok to get home in a reasonable time frame.

If the UK and EU really believe the rules are worthwhile, they should as a minimum require foreign airlines to observe them on the return leg of an intercontinental journey as well as the outbound journey.

Enforcement is lamentable

One of the key benefits of air passengers’ rights rules: an airline that cancels a flight is obliged to provide alternative transport as soon as possible. If another carrier has seats on the same day, the cancelling airline is supposed to buy tickets for passengers. But often carriers say they cannot or will not, with impunity.

Airlines are handed an absurd burden

All airlines have standby cover at their base: pilots and cabin crew who can step in at the last minute if necessary. But judges interpret the 261 rules to insist this is not good enough. To avoid delays on which they might have to pay out – such as a member of cabin crew falling ill, or the tragic death of the TAP Portugal pilot – airlines are apparently expected to have a captain and a senior member of cabin crew waiting on standby at every destination they serve.

In the context of aviation this is ridiculous. For example, Jet2 has two flights a week from Newcastle to Kefalonia in summer. A Supreme Court ruling indicates the carrier should be paying staff to sit around in a taverna drinking coffee all summer long, rather than actually flying people around on holiday.

Alternatively, Jet2 could take up a precious couple of seats on each plane to fly spare staff out and back, just in case.

None of this will happen, because passengers would be hard hit with higher fares and less choice. Instead, airlines will continue to operate as they do now – but with the knowledge that crew sickness will trigger compensation claims costing tens of thousands of pounds. This is not an overall passenger benefit, because the increased costs will be reflected in higher fares.

The UK could have opted out, at least for domestic flights

Brexit has conferred countless benefits on the nation, its proponents insist. One sensible move after leaving the UK would have been to come up with air passengers’ rights rules for domestic flights that are proportionate to the fare paid and the disruption incurred.

But Boris Johnson’s government forfeited the opportunity to jettison some bad Brussels legislation and instead simply copied and pasted the current law – pausing only to change the compensation amounts from euros to proper British pounds. A wasted opportunity to deploy rules that are fair, proportionate and enforceable.

Read more: Air passengers’ rights rules summarised

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks