Long way round: how does Russian airspace closure affect Asian flights?

Plane Talk: The current journey from London to Bangkok is typically 500 miles further than the direct track

Lucky Chris. He writes: “I am travelling to Thailand with Thai Airways for an island-hopping trip over Christmas.” I have been lucky enough to spend Christmas in Thailand, and it is a joy in all respects.

However, Chris has a concern: “I have flown to the far east several times before but before the Russian invasion of Ukraine. I imagine that the journey will be rather longer than usual given that no flights are now allowed to overfly either Russia or Ukraine. How long will the flights from London Heathrow to Bangkok be this time?”

Longer than I previously enjoyed, that’s for sure. Pilots rarely fly the precise direct track between two airports, due to factors such as wind direction and needing to comply with established air-traffic control corridors. But the “great circle” route is a useful starting point. It is the shortest distance from A to B on the surface of the earth. In the case of Heathrow to Bangkok, it is 5,958 miles.

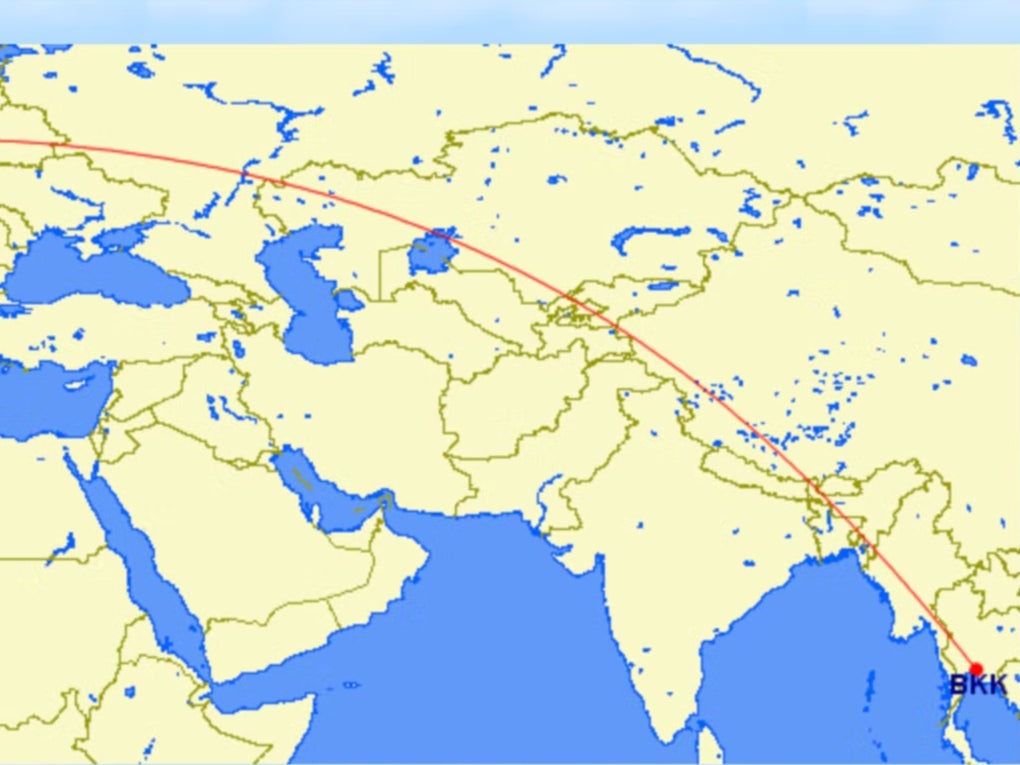

The Thai capital is well south of London, but the most direct route between Heathrow and Bangkok actually begins by heading slightly north of east. It parallels the Baltic coast of Germany and Poland, then traverses Belarus at its widest point from west to east and starts to cross southern Russia. Seven hundred miles later, the flightpath enters Kazakh skies for a couple of hours, followed by western China.

The opening up of the skies over Russia and China in the late 1980s transformed aviation between the UK and Asia by cutting many hundreds of miles from the existing routes. Together with improved aircraft technology, it allowed nonstop flights such as London-Bangkok for the first time.

Until the Kremlin decided to invade Ukraine earlier this year, such overflights had become routine. Russia extracted large sums in air-navigation charges, which airlines were prepared to pay in order to save fuel and reduce journey times. Quicker trips spell happier passengers and more efficient use of aircraft and crew.

The skies over Ukraine, too, were very busy with east-west overflights – tragically, MH17 was shot down over rebel-held eastern Ukraine in 2014 with the loss of 298 lives while on a routine Amsterdam-Kuala Lumpur flight. Unsurprisingly, when Russia invaded its southern neighbour in February this year, airspace was immediately closed over Ukraine on safety grounds. Russia shut its skies to most airlines – which were, in any case, giving the world’s largest country a wide berth.

As a result, much of the air traffic between Europe and southeast Asia is funnelled into a narrow corridor over the Black Sea and northern Turkey, well south of the Crimea. What with some often-tricky pathfinding over Iraq or Iran, the journey is typically 500 miles further than the direct track. At normal cruising speed, that equates to almost an hour of extra flying – or, if winds are uncooperative, even longer.

For Chris’s flight, the scheduled time is currently 11 hours 25 minutes – from pushing back at Heathrow to arriving at the stand at Bangkok. The airline will do all it can to reach the Thai capital as soon as possible, but passengers must be prepared to spend some time waiting on the ground for permission to depart.

The high demand for flightpaths in the air lanes of southeast Europe often causes delays. Last month my flight from Heathrow to Singapore was held on the ground for half an hour waiting for a time slot assigned by Eurocontrol in Brussels to cross the Balkans.

Finally, I fear Chris’s journey back will feel disagreeably long. At the end of a holiday everyone simply wants to get home as soon as possible. But the pilots will be battling against the jet stream all the way to London. The high altitude breeze that accelerated your progress east will impede progress, and with limited options available the captain may decide to take an even longer route to dodge the worst of the headwinds. But the annoyance of the journey home will fade much quicker than the memories of Christmas in Thailand.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks