The summer that changed my life: From a girls' trip in Malia to a 270-mile walk through England

Six writers recall the childhood trips that changed everything

The Norman invasion, 1997

By Daisy Buchanan

As the eldest of six girls, I found that our family holidays felt a little like a school trip, and a bit like going into war.

In August 1997, my patient, long-suffering parents loaded a Toyota Previa with snacks, games, comic books, bed linen, my sisters Beth (11), Gracie (eight), Jane (six), twins Maddy and Dotty (both four) and me (12). We were "the girls" – a bickering, chatty, chirpy unit of children who belted out Disney songs as one, quoted The Muppet Show at each other and occasionally put our fingers in each other's ears out of sheer boredom. We drove and sailed – on a Brittany Ferry – and drove again, to a remote farmhouse in Normandy.

We'd been to France a few times, and this trip was, initially, no different. There were cows in a neighbouring field that would eat your cardigan if you got too close. There were sturdy glass bottles of Orangina that had to be abandoned when they were claimed by wasps. And there were family dinners.

Usually we'd eat in the gîte, as the dining expenses for a family of eight were not inconsiderable. But occasionally we'd venture into town and try our luck in a gloomy dining room. Some proprietors were horrified by the sight of us; others would congratulate our parents. (French people who raise six children are eligible for a silver medal.)

But towards the end of the trip, one meal was different. The staff seemed to be pro-children ("Félicitations, monsieur!") and we ate our omelettes without incident. When we got up to go, we had to wait in a long line as the doorway was narrow. I was at the back, and the last to reach the exit. As I did so, I felt somebody squeeze something. There was a hand on my arse. I turned around. This had to be an accident, a mistake. The waiter who had been serving us smiled at me. My face was hot. I squeezed my eyes shut and walked away as quickly as I could, not daring to look back.

Puberty had not been pleasant, and I was doing my very best to ignore it. But I knew I wasn't exactly the same as my sisters any more. I couldn't join in, unselfconsciously, with whatever Maddy and Dotty were doing. I knew how I felt, but I couldn't control the way people would respond to the way I looked.

I told Beth and Gracie, who had one piece of advice. "Don't tell Dad!" I kept quiet, but if the memory ever surged up unbidden, I felt sick. To this day, I wonder whether it actually happened, whether I walked into the waiter's cupped hand. But the incident forced me to become more self-conscious. It separated me from my sisters. It made me realise that being an adult woman isn't just about gaining more autonomy – it can be a discovery of how little control you actually have.

Girls go wild in Malia, 2002

By Kate Wills

There were 15 of us. Still blinking from months of revising for AS-Levels, all wearing white T-shirts with our nicknames emblazoned on the back in pink. "McMuff", "Little Jo", um... "Willsy". But we didn't need great nicknames. We had just discovered that, despite being 17, we could get served Baileys on an airplane.

This was our first real holiday without parents, teachers or Brownie Guide leaders. We had been unleashed.

Descending en masse to Malia, a "party hotspot" in Crete, we were confronted with a Disneyland of debauchery. I can recall scenes that wouldn't have been out of place in the sleaziest hip-hop video (or a Hieronymus Bosch painting). We soon realised that we were a long, long way from our all-girls' grammar school in suburbia.

As anyone who has been cooped up at a single-sex school will understand, the mere sight of a potential mate, no matter how unattractive, sunburnt or drunk, is enough to send you into a frenzy. Which is probably why one of our number (a shy, bookish girl) spent the first night dry-humping a holiday rep on stage, while the crowd screamed and cheered, held up score cards to give her a mark out of 10 and then hosed her down with giant super-soakers.

We endured seven long days of fishbowls, foam parties and "heavy petting" in swimming pools (NOT ME! Honest, mum). I came home with a mouthful of ulcers (don't ask) and probably scurvy, considering the only fruit or vegetables I consumed all week were on the rim of a glass.

Looking back, I have no idea why our parents let us go. This was way before The Inbetweeners and Kavos Uncovered, so maybe they thought we were visiting Malia for the historical ruins. Which isn't such a stretch considering how geeky we were. But something about the combination of sun, sea, and spirits so strong they'd be illegal back home, made a group of normally sensible, swotty teenagers turn into girls gone wild.

There were some sobering moments. Four of us were chased down a backstreet by a cab driver screaming, "You are the English! You are here for the sex! I want the sex with you!" Luckily we managed to run back – in sky-high wedges – to our decrepit hotel unscathed. And I woke up a few times with no knowledge of how I'd got home. Or why there was a carrier bag of sick next to my bed.

I learnt some important truths on that holiday. Not least that drinking unknown quantities of a substance pertaining to be "Sex on the Beach", all day, in the sun, will make you projectile-vomit for 48 hours straight. But also that you don't need to do what everyone else is doing. For me, going on a "girls on tour" trip at 17 felt like a rite of passage. But, like hen dos, Freshers' Week and Christmas, the things that should be fun are often anything but. And that's OK.

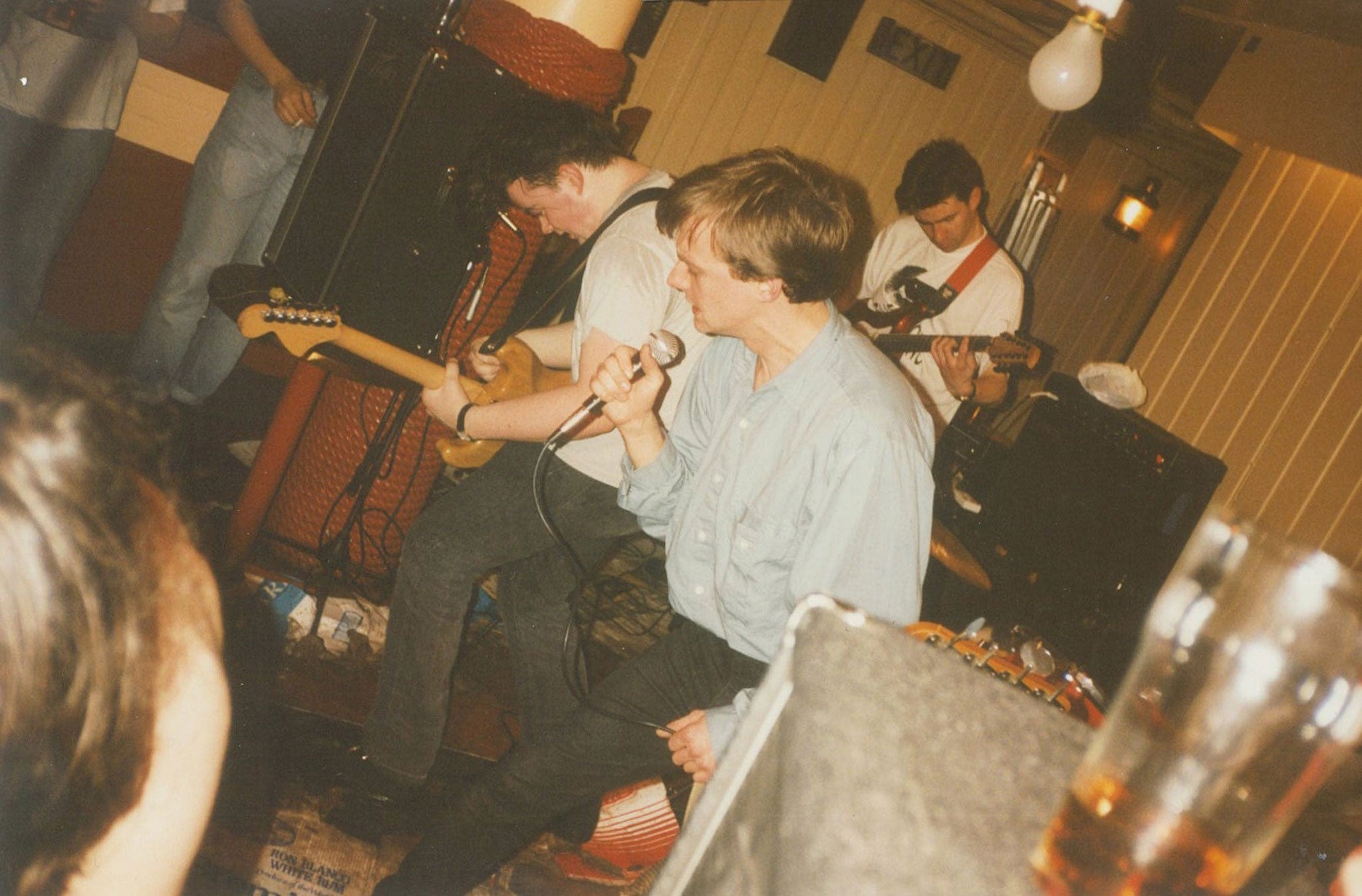

My first rock'n'roll tour, 1990

By Rhodri Marsden

My first 18 summer holidays followed a similar pattern. My parents would drive me down the M4 to visit one set of grandparents for a week, then drive me up the M6 to visit the others. Those were pleasant times, but in August 1990, the summer after my A-levels, it was time for me to do my own thing. The band I'd recently joined had decided to head to Scotland with a group of friends for a fortnight to play some gigs, spread our unique cultural message, and experience freedom, excitement and joy. But I quickly learnt that adult life doesn't always go to plan.

I stood on a street corner, waiting for the minibus. What arrived was a large, red furniture-removal van. "Cock-up at the hire company," explained our bass player. "This is all they had." He opened the back to reveal seven miserable people lying in the darkness, surrounded by sleeping bags, amplifiers and drums. As one person wrote in the tour diary, it was "like sitting in a hot gas oven, with the gas on but not lit, during an earthquake". I got in.

In a remarkable piece of logistical planning, our first gig was on the Isle of Lewis. The journey, which took the best part of 24 hours, passed through some breathtaking scenery. I didn't see it, because I was in the back of a furniture-removal van. I'd spend most of that fortnight in the back of that van. Tempers quickly frayed. Half the tour party announced they were going home. But they couldn't afford to. So they got back in the van.

That Stornoway gig was attended by 15 people who mainly chose to stare at a TV set showing the 1977 adventure film The Deep. As the tour proceeded, reward was repeatedly outstripped by effort expended.

The tour diary became a document of passive-aggressive messages and bad feeling, until an explosive entry in Inverness that began, "Hero worship, arrogance, selfishness, posing and snidery." One faction then sped home in a hire car they'd managed to pool the money for. The rest of us pressed on, stoically. When September arrived, we finally rumbled south in a furniture van that, if it could speak, would be able to tell you a great deal about the nature of human emotion.

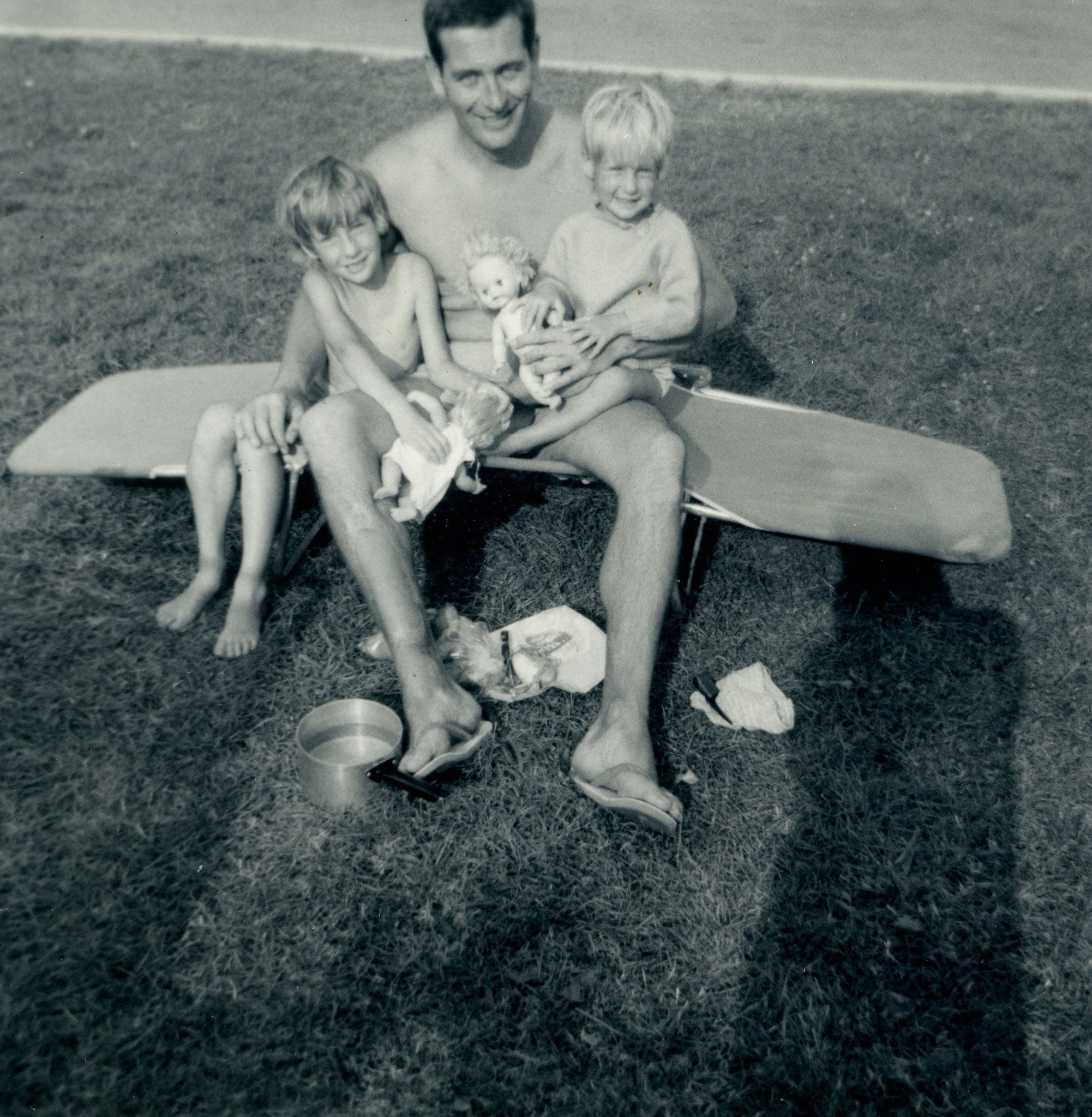

The neverending road trip, 1970

By Lisa Markwell

Travel was a quieter, more slow-paced pursuit before smartphones and tablets and even before audiobooks. God, it was boring.

Yet, in the 1970s, travel was also supposed to be exotic and exciting – and it was, for the neighbours we knew who were flying off to Tunisia and Spain. They were coming back with camel saddles and yard-wide sombreros.

The Markwells, meanwhile, were taking a road trip to Scotland, in a campervan. At best we'd return with some tablet (in those days, just a dense block of fudgy sugar). At worst, faces and bodies pitted with midgey bites.

Without an iPhone, Kindle or a story on tape, we made our own fun – but even the most convoluted game of I Spy eventually palled for Claire, eight, and me, then five. (A side note: in the 1970s, we children could mooch about untethered in the van, and often did. I have a feeling we even made hot drinks on the gas stove as dad negotiated the winding roads.)

At some point we must have got there, because there's a photograph of Dad hauling me to the summit of some low-level bit of the Grampians using a length of washing line. I'm pretty sure I whined and dug my heels in all the way. I had my white-blonde hair in a pixie cut that summer and looked rather adorable. My behaviour by no means matched.

The moment that stuck in my parents' minds, the one they like to remind me of many decades later and recount with glee to my own daughter, is of the journey back.

It was when the card games and the I Spy and sing-alongs had dried up. In desperation, my mum pondered what might be in the tanker snaking along the road in front of us, making our already slow progress through Derbyshire glacial. She was using the very last reserves of parental benevolence, it seems to me now. "Guess What's in the Tanker in Front" became the game. She guessed milk. My dad guessed petrol. Claire said "juice", and I announced loudly – in all likelihood very well aware of how awful it was to say this out loud, but too young and silly to think it through – "I think it's sh*t."

The next year we went to the Costa Brava.

The not-so-wicked stepmother, 1993

By Rebecca Armstrong

By the time I was 13, I'd done Disney World (bitterly disappointing to a seven-year-old who believed in magic but was surrounded by queues and plastic), visited two Canary Islands and been skiing twice. But the place I loved best in the world was Corsica.

The whole place smelt lovely, the ice creams were out of this world, and while my parents ate disgusting fish soup, I was allowed chunks of baguette smothered in pink garlic stuff (rouille) and grated cheese. There were also real, not made-up Disney, crenellations in the fortress town of Bonifacio, where the sea, hundreds of feet beneath the battlements, was unbelievably turquoise.

I'd been a few times as a child with my mum and dad – it was where I'd learnt to swim and dive – and it was heaven. So, despite my parents splitting up when I was 11, I lobbied hard for a return trip. I got my way, spending a fortnight with my dad, his new girlfriend and her son. What made things complicated was that said girlfriend was my mum's ex-best friend. I'm sure she would have preferred to go elsewhere, and to go there unencumbered by her former best mate's mini-me.

The summer that I was 13, though, that ill-fated liaison was over. My dad had a new girlfriend, whom he'd met on one of those skiing holidays. Where would we go on holiday? Corsica, I insisted. Where would we stay? In the beautiful (to me) self-catering apartments we'd stayed in before. I was given a choice of the exact place we – well, my dad and the ex-best-friend ex – had stayed, or a different set of rooms. Adult me shudders at what 13-year-old me made poor Helen, dad's new girlfriend, do. We'd stay in the same apartment, of course. I wanted things to be the same as before as much as possible, even though everything had changed.

Despite my insisting that she sleep in the same bed as her predecessor, Helen was a good sport. More so than I deserved, really, since I went on to blot my copybook on another trip away, this time to Ireland, when our B&B landlady, Mrs Hickey (really), referred to Helen as my mum. "She's not my mother!" I shot back (a response that still gets an airing more than 20 years later from the woman who went on to become my stepmother).

My memories of that Corsican summer are as idyllic and idiosyncratic as the other times we went there. We found a scorpion, and videoed it. We left it under a glass and found it next morning, thrillingly half-eaten by ants. And Helen got her own back, I realise now, by convincing me that she could teach me not to be ticklish. She didn't manage to stop me squealing, but I think she considered the process successful nonetheless.

My long walk to freedom, 1993

By Robert Epstein

"Smell that, boys. That's fresh countryside air, that is. Beautiful." I'd like to say that this was true. That the slightly odd gent who'd accompanied us for two days was breathing in the glory of the Lake District on a sunny, third morning. But the reality was that we were standing on a footbridge over the M62, and a relentless drizzle was slowly seeping through our so-called waterproofs.

It was July 1993, and I and three friends had decided, in the final school holiday before our A-level year, to take off on an adventure. Starting in the scenic town of Matlock in Derbyshire, we would hike the length of the Pennine Way (some 268 miles), plus a bit more, to end up in Edinburgh. (Or rather, in Peebles, a bus ride away – and home to far-cheaper B&Bs.) The walk would take us three weeks. We had it planned meticulously, using youth hostels along the way as each day's destination.

What we hadn't planned for were the setbacks: the unscalable scree mountains; the terrain so boggy it left one of our party bootless; the gnats so big and vicious that we looked as though we had leprosy; the rain that saturated 17 of our 21 days; the loner who tagged along and offered us Mars bars that we feared might be poisoned, before we convinced him that we really ought to part ways. You know, for reasons.

But – as painful the blisters, as dreadful the bites, as worried as we were that we might be murdered if we didn't get away from our newfound pal – setting off for yet another mizzle-ridden hill, I felt a growing sense of independence. And not just because spending such a long time in close quarters had resulted in inevitable teenage bickering and long sessions walking 50m in front of the others.

Independent me could eat what I wanted (it turns out you can have too much Kendal Mint Cake) and wear the same filthy clothes day after day after day – even if I did look like a 1930s throwback in my rolled-up shirt, puffy, beige trews and big-lapelled cagoule. And if we got lost (which we frequently did), no one was coming to help us – which was both blessing and curse.

Perhaps that was what Mr M62 was trying to tell us: that in adulthood, whatever you do, however you think, it's on your terms. It was a timely lesson in being self-reliant, because within a couple of years, after we had gone our separate university ways, I never saw my three fellow ramblers, and former really rather good friends, again. Quite why fades with memory – but perhaps I should have changed those trousers every so often after all…

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments