The world according to Simon Calder

For 20 years The Man Who Pays His Way has journeyed to the ends of the Earth for 'The Independent'. Here he looks back at the changes in travel he's witnessed over the past two decades

In May 1994 our travel habits were much the same as now. You and I enjoyed going to Paris or Rome for a weekend of culture and cuisine, to the Med for a week of sun and sea, and to the US for a fortnight's fly-drive. For something more adventurous, there's always Cuba.

That summer, I was aboard the first charter flight to the island from Gatwick, a pioneering package holiday that baffled everyone: the Cubans, on their first exposure to Brits abroad en masse, and the sunburnt holidaymakers bemused by the curious Cuban cocktail of sun, sea and socialism that rendered the most basic transaction in tourism – dos cervezas, por favor – a matter of Marxist uncertainty. Predictions of the imminent demise of both Castro and communism proved premature and Cuban holidays are still a bit wobbly. Yet for many aspects of travel, the past is not so much another country as a different planet. Travel is cheaper, easier and safer than 20 years ago. We can do more of it and enjoy richer experiences at the destination.

That trip to Paris? If, like most of us, you were time-rich, cash-poor in 1994, you would walk up to the window at Charing Cross station in London and buy a rail-sea-rail ticket. (That official on the concourse with de Gaulle-esque gold braid hat and walkie-talkie could well have been Mark Smith, then station manager – better known today as the global rail guru who runs Seat61.com). You spent £60 and all day reaching the French capital.

A flight? Before Eurostar started running high-speed trains through the Channel Tunnel in November 1994, Heathrow-Paris Charles de Gaulle was the busiest international air route in the world (today, it barely troubles the scorers). But fares on British Airways, Air France and British Midland were frustratingly high. To find anything cheaper involved finding a youth-and-student travel specialist not overly pedantic about age or academic status and ending up on a slow Air UK propeller plane from Stansted. At least you could reach the Essex airport quickly; the rail journey from London was five minutes faster than today.

The Med? Off you went to the travel agent to be sold a package holiday for a week or a fortnight. Prices were keen: the first low-cost airlines, after all, were the charter carriers. But choice was limited and durations were fixed. The big tour operators – Airtours, First Choice, Thomas Cook and Thomson – ordained the terms for travel. Once the low-cost carriers arrived, passengers started voting with their feet. The package-holiday companies lost the plot. Today, the holidays arm of easyJet is on course to become Britain's third-biggest tour operator, after Thomson (which took over First Choice) and Thomas Cook (which devoured Airtours/MyTravel).

The low-cost airlines have been responsible for an astonishing expansion of the options for short-haul flying, and the equally remarkable contraction of air fares. Britain and Ireland have led Europe in transforming travel. First out of the blocks was a funny little Irish airline, Ryanair, which had nearly gone bust before a young accountant named Michael O'Leary took over. In October 1995 it took advantage of "open skies" rules to shuttle between Stansted and Prestwick. A month later, easyJet started up between Luton and Glasgow with a one-way fare of £29 – at the time revolutionary.

Today easyJet and Ryanair are the most successful airlines in Europe, carrying an astonishing 400,000 people a day between them. The £29 Luton-Glasgow fare is still available, though £13 goes straight to the Chancellor in air passenger duty. APD, introduced in 1995 with a £5 rate, has become the Treasury's all-time favourite tax: easy to collect and difficult to avoid. The original no-frills mantra maintained that the business model worked only on flights of two hours or less, but travellers have demonstrated that they are happy to put up with non-reclining seats for five hours or more, if the price is right and the destination enticing enough. Morocco and Egypt are now far more accessible.

The single most dramatic change for travellers? The internet. It was made for travel – connecting the disparate needs of millions of individuals with instant access to the building blocks of travel. The web has also enabled airlines to cut fares, starting with easyJet – which has never issued a paper ticket.

Twenty years ago, British Airways spent almost as much on "distribution" – commission on flights, plus the tangled bureaucracy involved in handling flight coupons – as it did on fuel, and kept fares high to compensate. In those days only a fool would book a long-haul flight direct: by cutting in the middle-man, you could save a fortune. The best deal in 1994 was a Heathrow-Los Angeles/New York-Heathrow open-jaw ticket on Virgin Atlantic for £179, available through Trailfinders. To preview the 1994 World Cup, I bought one and combined it with a £300 Delta airpass – a month's worth of travel on the airline's US network, which unlocked America's cities in all their flamboyant might.

Today, you might well choose to go through an agent for their expertise, but for the keenest fare (£483 for the LA/New York trip in 2014) virgin-atlantic.com is probably your best bet.

Online travel doesn't always end well. As the obligation to use the web to check in for flights or visit the US intensifies, the opportunities for those without the traveller's best interests at heart intensifies. Tap "Turkish visa" into Google to see the scope for wasting a fortune by inadvertently going through a commercial site rather than the official website.

How to plan a trip? For a decade from 1994, travel-guide firms enjoyed the best of times. Guidebook sales soared in line with multiplying travel options: after the Yugoslav civil war, for example, the Dalmatian coast was rebooted as Croatia and became great independent traveller territory, and Dubai transitted from a desert refuelling stop to Manhattan-on-the-Gulf. But when content such as TripAdvisor's hotel reviews and even The Independent's 48 hours city guides became easy to find online, sales began to slide. The BBC had bold ideas for exploiting the wealth of data and opinion in Lonely Planet when it took over the firm in 2007. The promise foundered and the travel-guide publisher was sold for less than half the price the BBC paid.

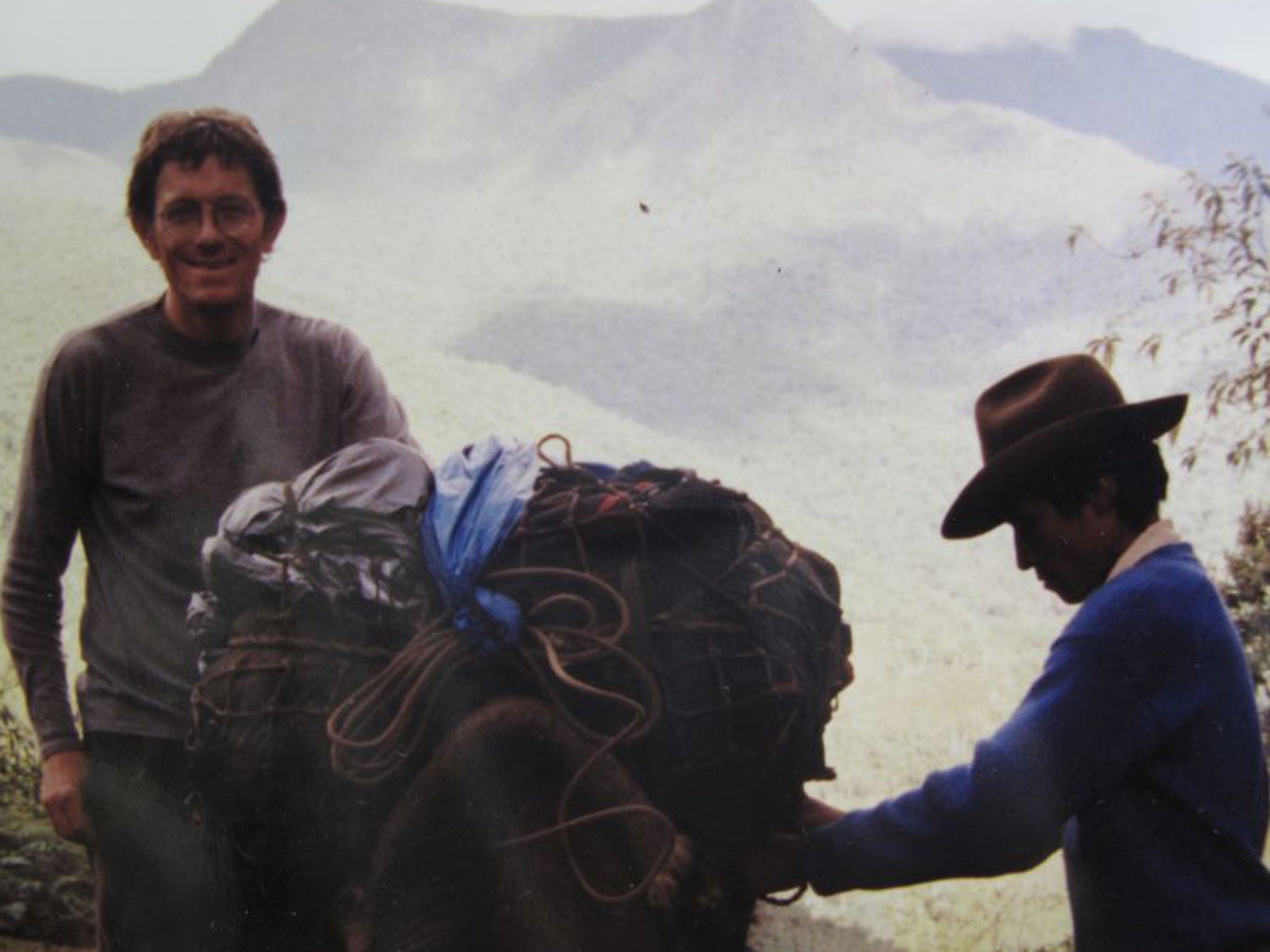

With or without a guidebook, travel is safer – which, given the climate of fear about terrorism, may sound unlikely. Threats to civilised travellers from extremism were rare in 1994. The only organisation that vowed harm to tourists was Peru's Shining Path, but with its leader captured the long and winding Inca Trail to Machu Picchu seemed safe – it remains the great South American journey.

In 1997 visitors to Luxor were massacred; a year later, adventure travellers were targetted in Yemen; in this century, Bali, Sharm el Sheikh and Mumbai became venues for the wanton slaughter of innocent tourists and locals. Yet far fewer British travellers die at the hands of terrorists than on European roads – where, thankfully, safety is improving. The highway carnage in our favourite nations, France and Spain, has almost halved.

Hitch-hiking remains high on my personal risk register, not because of malevolent drivers but because of the inherent risks of road travel. Thumbing is a valuable weapon in the traveller's armoury whether you are trying to reach base camp for an ascent of Japan's majestic symbol, Mount Fuji (as I was in 1996) or merely making up for a cancelled train in Cumbria (as I did last Monday).

Aviation's safety record has gone from excellent to astonishing. In 1994, British airlines had enjoyed five years without a fatal accident involving a passenger jet. Today that run has extended to 25 years – even though far more people are flying. The UK has earned the world's best aviation record thanks to an obsessive safety culture embedded in airlines and air-traffic controllers – plus occasional outstanding airmanship at Heathrow. In 1997, a Virgin Atlantic jet from Los Angeles landed safely on three wheels. In 2008, BA flight 38 from Beijing lost power on the final approach; the Boeing 777 was written off in the crash landing, but all on board survived, mostly uninjured.

In 1994, the world's most exciting routine landing was at Hong Kong's Kai Tak airport, which involved 747 pilots swerving past apartment blocks close enough to see which TV channel the residents were watching. A shiny new airport replaced it in 1998, and it has been reinvented as a cruise-ship terminal. But if you make a happy landing in what is now a "Special Autonomous Region" of China, old-school transportation still prevails in the clunky but civilised shape of Hong Kong's double-deck trams to Happy Valley and beyond.

Airport security remains both the most uncivilised aspect of the travel process and the most worrying safety concern. The slaughter of 11 September 2001 exposed a fatal flaw. The system was designed to keep specific threats – guns and bombs – off planes, and the 9/11 hijackers passed through the standard airport security search. The rules tightened afterwards to exclude blades. In 2006 they were turned up a notch: liquids (and even, in my recent experience, cheese) were added to list of perceived threats. Yet there is something wrong with a system that presumes every passenger to be an international terrorist until they pass through a checkpoint, whereupon they and their possessions are deemed to present no threat. It's pure list-ticking: just because systems can detect and confiscate a ripe slab of Brie, it doesn't follow that the skies are safe from those with evil intent.

That concern apart, this generation enjoys unprecedented freedom to travel. I am celebrating this weekend with a trip to a Spanish city that is now half as expensive and a quarter as tricky to reach as it was in 1994: La Coruña in Galicia. These days, paying your way costs less and delivers more.

Wish you were here? With friends in exotic places in possession of cheap technology, you can be. Skype and FaceTime have superseded poste restante and Instagram renders postcards obsolete. The low-cost revolution combined with the ability to access a world's worth of information through a smartphone have democratised travel and disseminated its virtues. Our minds are broader, our understanding is deeper, our wealth is spread more widely and our memories are deeper: of friendly faces, joyful days and enchanting nights a long way from home.

1994 vs 2014

Cruise news

Then: Airtours launched the cheapest-ever cruises, costing £399 for four days in the Canaries.

Now: the number of British cruise passengers has quadrupled, with around £100 per person per night still a reasonable price.

Snow options

Then: you either flew on a package to the Alps or piled into the car and drove south.

Now: a no-frills flight to Geneva and an independently booked apartment have become the norm.

Holiday money

Then: traveller's cheques, francs, lire, pesetas.

Now: pre-loaded travel money card, euros.

Welcome arrivals

Angel of the North, easyJet, Eden Project, Eurostar, Guggenheim Bilbao, London Eye, Megabus, Tate Modern, The Independent Traveller.

Gone but not forgotten

British Midland (though BMI Regional continues), Concorde, Jill Dando, Holiday programme, Sir Freddie Laker, Eric Newby, Alan Whicker.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks