International Dylan Day: The streets, pubs and landscapes where Dylan Thomas found inspiration

To celebrate the first International Dylan Day on Thursday, Phil Carradice, Griff Rhys Jones and Andrew Lycett share their journeys through the snug suburban streets where he grew up, the pubs where he swilled, his city and his countryside.

UPLANDS

by Phil Carradice

Think of Dylan Thomas and your mind invariably turns to what was the most influential and significant of all locations for him, the Uplands area of Swansea.

This sprawling suburban enclave was crucial to the young Dylan – for his development as a writer and as an individual. It was where he was born and, arguably, with an iron-fast hold upon his imagination, it was a place he never really left.

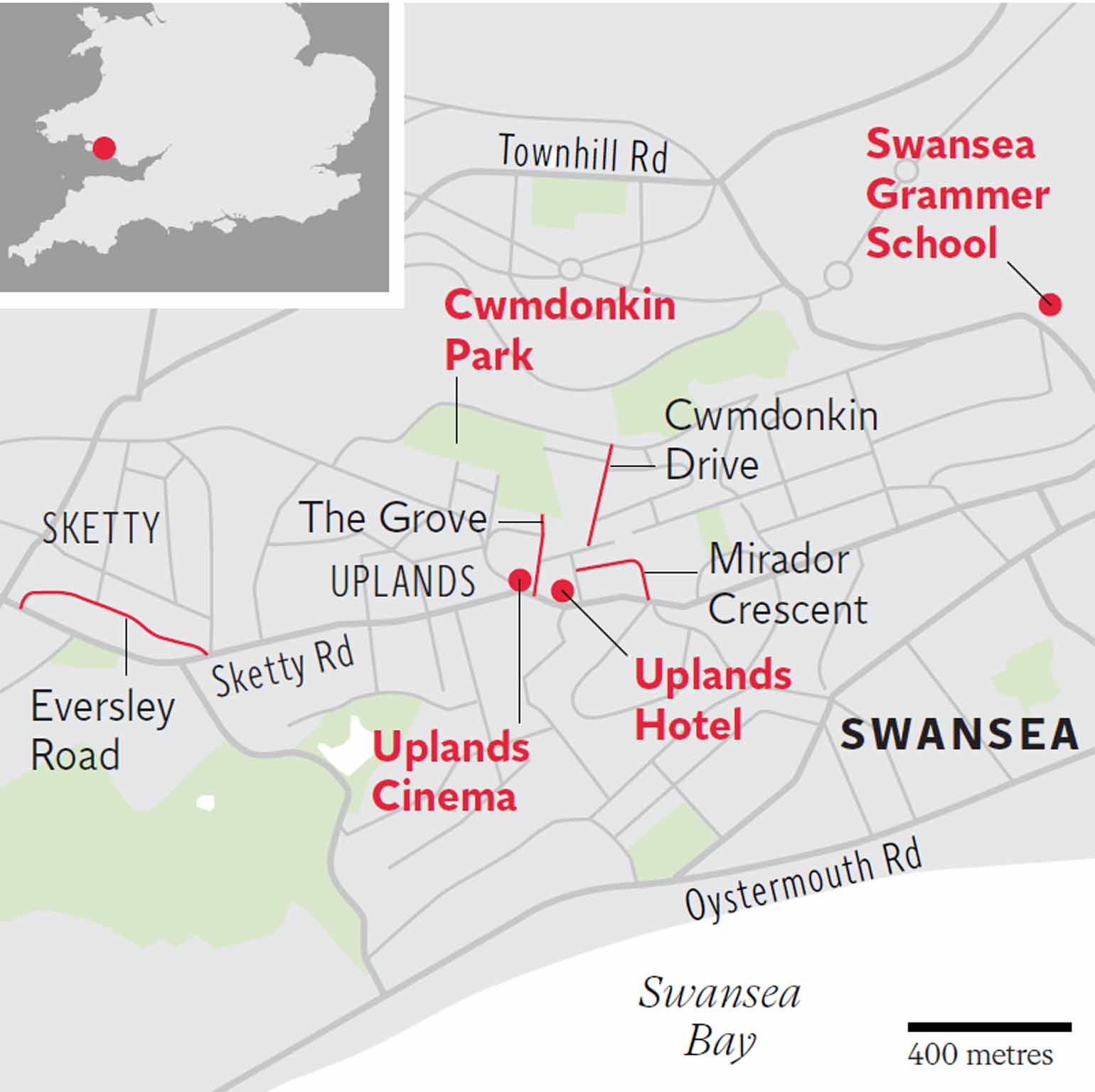

The haunts of our childhood have a claim on most of us. But with Dylan Thomas that claim was powerful beyond belief, almost pathological. Even after he became grounded in Carmanthenshire for the last four years of his life, the Uplands continued to exercise an incredible pull on his imagination. Dylan's decline, his long slow slide towards the grave, is symbolised by his longing for a long-gone innocence. He mourned for Cwmdonkin Park and the wonder-filled streets of his childhood, for the Uplands Cinema and the warm comfort of Warmley, Dan Jones' house in Eversley Road. Above all he mourned for his home, 5 Cwmdonkin Drive. It was this mourning that fuelled poems like "The Hunchback in the Park" and the stories in Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog.

Dylan was, arguably, a child who never grew up, gifted – or cursed – with the amorality of all young children. Whatever he wanted he took, that was his right, just as it had been his right to help himself to handfuls of wine gums from Mrs Ferguson's sweet shop in The Grove when he was 10 years old. He lied at will, as children will do, and had the uncanny ability to be all things to all people, like any precocious four- or five-year-old.

In later life, emotionally, Dylan Thomas never progressed beyond childhood, and there is little doubt that much of the responsibility for this emotional stultification rests with his parents. His mother Florence created a womblike security where every wish was catered for, every dream fulfilled. She protected, she embraced, she virtually embalmed him in a sickly-sweet, cloying embrace – and the house in Cwmdonkin Drive was a solid physical manifestation of his mother's love.

It is natural for any mother to want to protect her children but Florence took it to extremes – and Dylan took advantage. He played on his mother's fears: the story of him cutting his knee with a penknife then telling Florence the blood had come from his ears is just one example of the lengths to which he would go to get that extra ounce of fussing and spoiling.

Dylan's was a small, enclosed world, at least until he went to Swansea Grammar School at the age of 11. It was, at most, a mile wide, from the town centre to the outer reaches of the Uplands and Sketty, from Cwmdonkin Drive southwards to the beach and sea. The very smallness of this world meant safety and security, and within that Uplands security Dylan could reign supreme.

He was the king of Cwmdonkin Park, lord of the back seats in the flea-pit. His was the right to steal sweets and cigarettes from Mrs Ferguson, to knock on doors and run. Even at Mrs Hole's Dame School in Mirador Crescent, where he received his first formal education, he held the position of honour on the lap of Mrs Hole's daughter. And even in adolescence, the Uplands continued to provide security. A brief period as a reporter on the local paper was followed by three years in the safety and security of his room in 5 Cwmdonkin Drive, a sanctuary that was familiar enough to let him express himself in a monumental welter of poems.

The Uplands Hotel was his first "drinking hole" (although it was also his father's bolt hole and could, therefore, be used only sparingly). But there were still friends like composer Daniel Jones, painter Alfred Janes and communist grocer Bert Trick to meet and talk with. Bear them in mind and it is almost impossible to stress the significance of the Uplands on him as a writer.

It is wrong to say that Dylan left Swansea to go to London – because he did not really leave. A fortnight, three weeks, away from Mam and Cwmdonkin Drive was about all he could manage before he fled back to suburban Swansea, a whole world away from his supposed bohemian longings. And back in the Uplands the spoiling and the fussing started again.

FITZROVIA

by Griff Rhys Jones

Fitzrovia still retains the scrabbling inner city mix that Dylan Thomas plunged into when he first came to London in 1934, living for a while at 12 Fitzroy Street. He called it "capital punishment" – but the creative centre of Britain lies in these streets. Not perhaps the airy-fairy-spiritual creative centre, but certainly that of the Grub Street, hack coterie; the commercial, living-off-their-wits writers, artists and chancers.

It was in Fitzrovia that Dylan met his future wife Caitlin Macnamara, in The Wheatsheaf on Rathbone Place, laying his beer-fuddled head in her lap and stealing her away from Augustus John. They took lodgings in Conway Street and he drank in every pub in the district. He roamed the restaurants and clubs. He worked at the BBC and played nightly to his amateur audiences across Fitzrovia.

Dylan told the writer Lawrence Durrell that London "gave him the willies". He wrote that it was "an insane city" and it "filled him with terror". His greatest poetry seems to long for the pantheistic energy of nature. But was he not as much a London writer as a Welsh one? Sometimes he yearned to escape from "promiscuity, booze, coloured shirts, too much talk, too little work", but he kept coming back for another round. There was always a duality to Dylan and his work.

Dylan spent most of the war working in London but, by the end of the Blitz, he was beginning to weary of it. Not that this poet grew tired of London; rather, London seemed to wear him out. The landlords of various pubs claim they never saw him drunk. But when the Rimbaud of Cwmdonkin Drive had first hurried to join his artist friends in their digs, to sleep on floors and venture slightly nervously into the pubs of literary and artistic renown, he had become addicted to the everlasting party. As his friend Trevor Hughes noted, in the Fitzroy Tavern, "Dylan did not want to drink – no, he wanted to talk."

By all accounts, there was no single Dylan Thomas loose in London in the 1930s and 1940s. For every account of the "ugly suckling", as Geoffrey Grigson and his friends dubbed him – the sponger, or the weaving drunk – there are others of his excessive generosity with money and his sober dedication to work. He was quite capable of behaving primly in the company of TS Eliot and Edith Sitwell and then "letting the side down" at some gruesome, organised dinner.

The writer Julian MacLaren-Ross remembered that he once suggested they get a bottle in: "'Whisky? In the office?' He seemed absolutely appalled." In the 1940s the two of them wrote propaganda films for the Ministry of Information, but Dylan arrived on time, wore a suit and was liable to work more conscientiously than Julian thought necessary. That may well have changed. But if so, there are not many who seem to have any sympathy for the road he travelled.

Surely, it was the double demands of his life – the curiosity for company, the furious clowning, the infantilism, the immediate and instant – that fuelled his most vivid verse. Why does Under Milk Wood continue to enthral when Eliot's The Family Reunion sits on the shelf? It reaches down. It sets itself amongst ordinary people. It has the public bar and the post office and the chatterbox stranger written all through it. And perhaps a certain straightforward commercial nous? It was the post-propaganda film Dylan who wrote that work.

Dylan disdained the label of surrealist, but his characters use their fantasies to free themselves from the buttoned-up village and its closed minds. An artist could properly lead the Bohemian life, alongside nude models, raucous painters and their mistresses, and the "regulars, wits and bums" that MacLaren-Ross described.

Dylan Thomas was not a household name until 1945 and the success of his collection of poems Deaths and Entrances. Before that, he was known to (and part of) an informed circle. He worked in a recognisable world of the freelance media creative dogsbody. Journalism was not his métier. Instead he picked up propaganda films or bits of short story. Perhaps today he would have written television. Then he worked for the radio, and as much as an actor or "voice" as a writer, often turning out for John Arlott, later the cricket commentator, who seldom had cause to complain of lateness or indifference.

By the late 1940s Dylan was making 20 radio appearances a year, turning up to read or as a critic or a guest on a panel. He needed Fitzrovia, and it was important to him – even if it wasn't always conducive to his productivity.

OXFORD

by Andrew Lycett

They are the least celebrated years of Dylan Thomas' brief life – the ones he spent in the city and environs of Oxford between 1946 and 1949, as he negotiated the difficult transition between the frenzy of existence in London during the Second World War and his return to the tranquillity of Carmarthenshire.

But this was not a wasted period. Dylan was in great demand as a multi-faceted contributor to the BBC. He worked hard, regularly taking the train to London, where he also wrote scripts for Gainsborough and Ealing film studios. Particularly after he went to live in South Leigh, nine miles west of Oxford, he enjoyed a proper family life, mixing with villagers and absorbing material which, it is now clear, helped in the genesis of his great play for voices, Under Milk Wood.

In an ideal world, Dylan Thomas might have gone to Oxford himself, as an undergraduate. His schoolmaster father had taken a first class degree at Aberystwyth and would have loved his son to study there, or even at Oxford. But, for all his intellectual precocity, Dylan was not academic material.

He was first sighted in Oxford in November 1941 when the young poet Sidney Keyes (soon to lose his life in the war) invited him to address the English Club. Philip Larkin, a student at St John's, remembered him appreciatively: "Hell of a fine man: little, snubby, hopelessly pissed bloke who made hundreds of cracks and read parodies of everybody in appropriate voices."

In March 1946, shortly after the publication of Deaths and Entrances, his fourth and most eclectic collection of poems, Dylan returned to live in the university town – at the unlikely invitation of Margaret Taylor, wife of the historian A J P Taylor, whom he had met a decade earlier. She offered Dylan and his young family the summerhouse attached to Holywell Ford, the Taylors' own dwelling in the grounds of Magdalen College. Situated beside a small stream, it was damp with no running water – although there was gas and electricity – and his two children had to sleep in the main house.

Dylan had nowhere else to go, but at least he was in easy commuting distance of the BBC. And when in Oxford he made a name for himself, both in donnish circles and among the wider student population, propping up the bars in pubs such as the Turf Tavern, the George Hotel and the Gloucester. He even wrote an affectionate (though unpublished) poem about the university in which he muses on what might have been: "Ah, not for me the windblown scarf,/ The bicycle to the Trout, the arm in arm sweatered swing, Marx in a punt, Firbank aloud round the gas-ring".

He couldn't stay forever at Holywell Ford. So, after spending some months in Italy in 1947, courtesy of a Society of Authors grant arranged by his friend Edith Sitwell, Margaret Taylor fixed him up with a new place to live – the grand-sounding Manor House in the village of South Leigh near Eynsham.

Once again the facilities were sparse, with no electricity or inside lavatory. Most of the mains water was drawn off by a cattle drinking trough halfway up the drive. But there were compensations. In those days the village had a railway, which meant Dylan could easily travel to Oxford and London (Bill Mitchell, the station master, would keep the train waiting if he saw Dylan heaving into view). A lively social life centred on the village pub, the Mason's Arms, where Dylan was known for his skills at the pub game shove ha'penny. And Dylan often travelled by bicycle to The Fleece, in nearby Witney – which provided the unlikely location for a roving BBC programme he introduced called Country Magazine, about the Windrush Valley.

Although Dylan was busy working on radio and film scripts, and made advances in writing Under Milk Wood, his main poetic achievement in this period was the long and complex In Country Sleep, the first draft of which was written in Italy. In an effort to improve his productivity, Margaret Taylor gave him a gypsy caravan so he could work in a field next to Manor House, untroubled by family demands.

Occasionally Dylan's Oxford student friends made their way to South Leigh. He spent a boozy day with Paul Redgrave, investigating the Mistletoe Bough legend in Minster Lovell, five miles away. After an unsuccessful attempt to locate this reputed local provenance of an ancient folk tale, they ended back at Redgrave's cottage at Church Hanborough, where Dylan was so fascinated by the story of a poltergeist in the local church that he insisted on reading one of John Donne's sermons from the pulpit there.

In March 1949 he embarked on a trip to Czechoslovakia – and when he returned, his agreeable experiment with English university and country life was over. He moved to Laugharne, where the ever attentive Margaret Taylor had bought him the Boathouse; the ideal poet's residence, overlooking the Taf Estuary – and this has since become the most potent visible symbol of his life and career. µ

These essays are edited extracts from 'A Dylan Odyssey' (£20, Graffeg), a collection of collection of literary tours that is published on 14 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks