2016: the year we had to admit the experts got it wrong

For those on the centre left, it was an annus horriblis – but there was eventually something to cheer

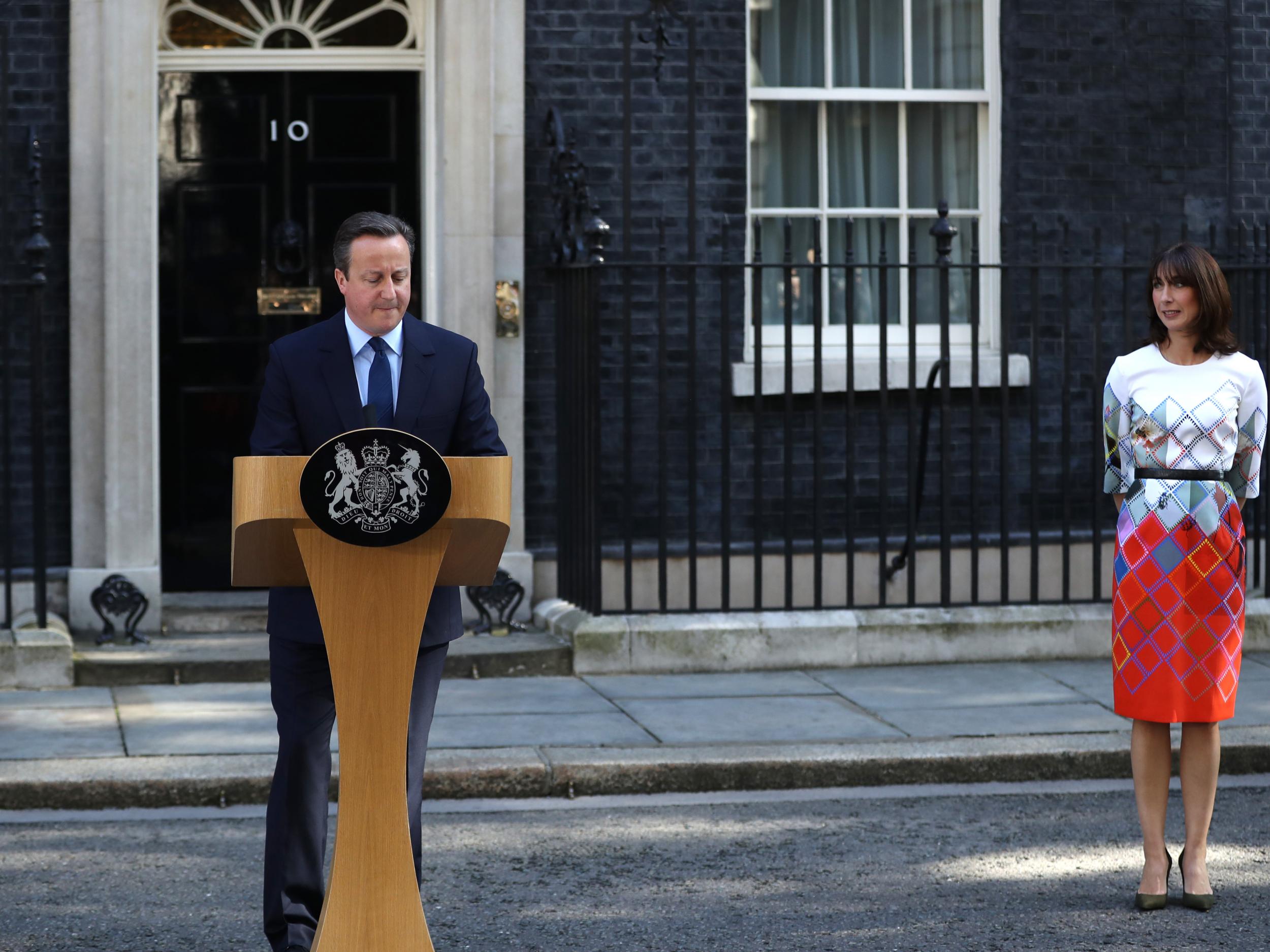

“Oh, and by the way, the Prime Minister has resigned.” That wasn’t quite what the BBC said on 24 June, but almost. Remarkably, David Cameron’s decision to stand down was relegated to the third item of the BBC News bulletin – behind the vote for Brexit and the ensuing turmoil on global financial markets.

It was a momentous day in a momentous year that also brought us Donald Trump’s election as US President; a failed coup against Jeremy Corbyn and the murder of a much-loved Labour MP on the streets of her constituency.

Arguably, Cameron’s fate was sealed in February, when he returned from Brussels with a threadbare new deal after renegotiating the UK’s EU membership terms. Although he won some curbs on benefits claimed by EU migrants, his fellow EU leaders would not let him restrict the number of migrants. So when the referendum came, the Remain camp had very little to say on what became the most salient issue – immigration.

Nigel Farage was frozen out of the official Vote Leave campaign but, after saying it would not join him in playing on public anxiety about immigration, it did precisely that. Farage’s crude populism, which divided voters, was given a respectable veneer by Boris Johnson and Michael Gove, the figureheads of Vote Leave. It was a powerful combination, and proved lethal for Cameron. He avoided the immigration issue, calculating that a relentless message on the economic risks of leaving the EU would triumph. It was a catastrophic misjudgement: by 52 to 48 per cent, the British people voted to leave the EU.

Perhaps we should not have been so surprised. A three-month referendum campaign was never going to turn a 30-year tide of hostile press coverage of the EU. Even Europhiles like Tony Blair missed their moment to “sell” the EU to the public.

Many voters seized the moment to make an anti-establishment protest after years of wage stagnation and being “left behind” by globalisation. Some 2.8 million people who voted in the June referendum had not bothered to vote in the 2015 general election. They were “missed” by the opinion pollsters, who therefore got the referendum wrong.

The result sparked a Shakespearian drama in the Conservative Party. When Cameron bowed to the inevitable and resigned, the front-runner to succeed him was Johnson. Yet there were doubts about his suitability for the top job. Genuinely shaken by his part in Cameron’s downfall, Johnson failed to focus on the Tory leadership election. Gove, his fellow co-leader of Vote Leave, knifed Boris just before his campaign launch and ran himself. The act of betrayal left Gove without enough support from Tory MPs. Soon Theresa May was the only candidate left standing after her only rival, Andrea Leadsom, self-destructed.

After expecting a two-month contest against Leadsom, the then Home Secretary had just two days to move into Downing Street. She made Johnson her Foreign Secretary, another of the year’s great surprises and its quickest comeback. As May purged the Government of Cameron allies, the Eurosceptics David Davis and Liam Fox were also given key jobs implementing Brexit. May, a reluctant Remainer who kept her head down during the referendum battle, tried to win her party’s trust by making control of migration her “red line” in the EU negotiations.

The complexity of Brexit made it a difficult baptism for May. She ended the year without the “plan for Brexit” demanded by MPs and with the Cabinet’s crucial decisions put off until the New Year. But May provided stability and reassurance when the country desperately needed it. She and her party were rewarded with a commanding lead in the opinion polls.

The seismic shock of Brexit helped to prepare the ground for another earthquake. Trump, the Republican outsider in the US presidential race against the Washington insider Hillary Clinton, urged Americans to copy Britain’s “independence day” and, after his remarkable victory in November, was able to celebrate “Brexit plus, plus, plus”.

US voters staged their own anti-establishment protest. Although the parallels can be overdone, struggling white working-class voters again felt neglected by the political class: “Washington,” like “Westminster”, became a dirty word. Trump’s “America first” policy echoed the nationalist, anti-immigration message of the Leave campaign. He was lucky to have Clinton as his opponent; the Democrats lacked a clear message and failed to connect with working-class people who, like many who voted for Brexit, felt they had nothing to lose by backing Trump.

Both results were a defeat for the liberal elite which had dominated politics on both sides of the Atlantic. Nationalism triumphed over globalism in a bad year for international bodies. Warnings by the IMF and OECD against Brexit were ignored as voters seemed to agree with Gove that we “have had enough of experts”. The EU was shaken by the decision by its second largest economy to leave. The future of Nato and international trade deals were called into question by Trump’s victory.

In the short term, the arrival of President Trump will have a bigger impact on an uncertain world but he may last for only four years. Whatever form Brexit takes, it will transform the UK’s relationship with the EU forever; there will be no going back.

One man who could celebrate both events was Farage – along with May, the one to benefit most in a tumultuous year. Love him or hate him, Farage secured the referendum and then achieved what he went into politics for, a rare triumph. He also advised Trump and the lasting image of 2016 is the grinning faces of the former Ukip leader and President-elect in the golden lift of Trump Tower in New York. The anti-establishment forces were suddenly the new establishment. Farage left the UK Government looking flat-footed after it banked on a Clinton victory – a salutary lesson that nothing could be taken for granted in the new world.

The shockwaves from the referendum also destabilised Jeremy Corbyn, who fought a half-hearted campaign even though Labour was committed to staying in the EU. The backlash from Labour MPs led to a vote of no confidence in Corbyn and a leadership challenge by Owen Smith. But it was a chaotic, premature coup and Smith, running as a more competent version of Corbyn, failed to woo enough of Labour’s fast-growing 600,000-strong membership. In September, Corbyn won a bigger mandate than a year earlier, beating his challenger by 62 to 38 per cent.

Labour’s three-month leadership contest summed up its wasted, inward-looking year and was in sharp contrast to the three weeks it took to install May as Cameron’s successor. Although Sadiq Khan won the London Mayoralty for Labour in May, he kept his distance from Corbyn. The Labour leader sharpened his act at Prime Minister’s Questions but his party made little headway; it often looked irrelevant and invisible, and anything but a government-in-waiting.

For those on the centre left, it was annus horriblis. But there was eventually something to cheer when Liberal Democrats showed they are back in business by winning the Richmond Park by-election in December against the Tory-turned-independent Zac Goldsmith.

Overall, however, it was the year of the populist and politics had a dark side. The attacks and bullying on social media by right and left got nastier. America saw “fake news” stories such as the claim that the Pope backed Trump. Britain, too, became a less tolerant country; hate crimes rose after the referendum.

The nadir was not Brexit or Trump but the murder in June of Jo Cox, a pro-EU rising Labour star and mother of two young children, outside her constituency surgery in Batley and Spen, Yorkshire. Her political epitaph – we have “far more in common with each other than things that divide us” – was tested to destruction in 2016. But it provided a ray of light for those hoping that the year was a one-off rather than the start of a dangerous new era.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks