It’s time psychiatrists stopped stereotyping women with personality disorders – we can speak for ourselves

I do not have a beast within me, as Peter Tyrer's new book cover implies, waiting to be tamed by an expert mental health professional. It is irresponsible, painful and stigmatising to evoke this image

Taming the Beast Within, a new book on personality disorder diagnosis, has just been released. It features a small faceless monster on its blood-red cover. I was diagnosed with borderline personality disorder five years ago, so presumably this is supposed to represent my inner beast. The book’s author is professor of psychiatry Peter Tyrer, with a foreword by Stephen Fry.

Conventional wisdom says not to judge a book by its cover – but this book’s cover is clearly judging people like me. Covers and titles matter. They stay with people long after the content and make an impression on those who never read further. I do not have a beast within me, waiting to be tamed by an expert mental health professional. It is irresponsible, painful and stigmatising to evoke this image, whether the text itself subverts it or not.

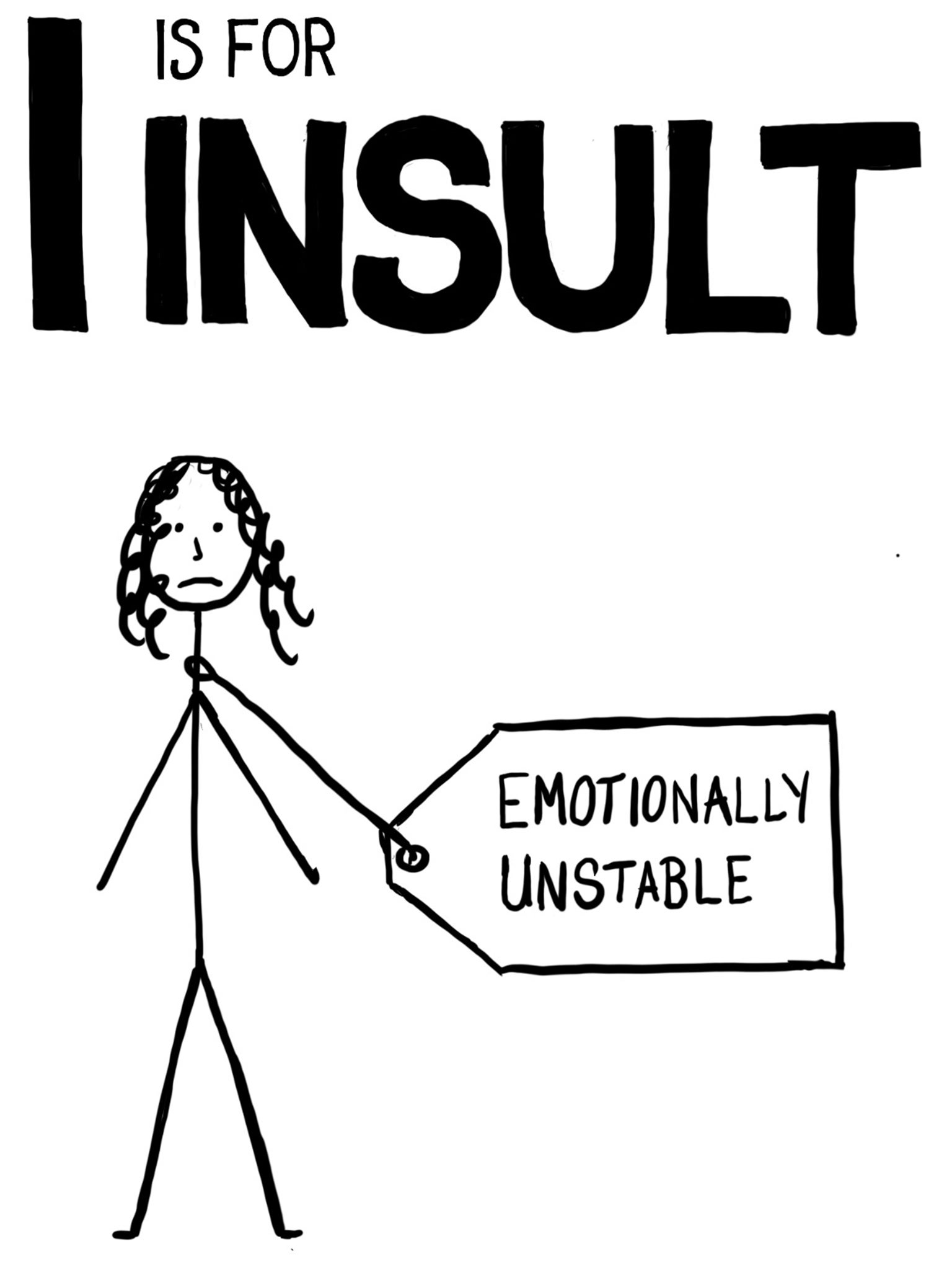

Borderline personality disorder, sometimes flatteringly known as emotionally unstable personality disorder, is the most well-known personality disorder diagnosis. Seventy-five per cent of those diagnosed are female. It is a label often given to women who fail to meet society’s standards for appropriately expressing emotion – we are too intense and too angry. This is usually because those standards have failed to protect us from trauma and have not allowed us to speak about it. For many, that trauma was sexual abuse, domestic violence and/or marginalisation due to sexuality, gender identity, race, poverty, neurodivergence or any other marker of difference.

For me, it was a combination of difficult events and relationships, set against the backdrop of an environment which invalidated at every turn. My younger self learned through a thousand mundane interactions that a confident woman will always be seen as arrogant, but that nothing less than perfection is acceptable. I learned that my queerness is dangerous – I wasn’t born when Section 28 became law, but I first heard the word “lesbian” as a playground insult. And I learned that to be a girl in a public space is more dangerous still. I responded to these experiences by retreating into bulimia, self-harm and an ever-tightening cycle of academic perfectionism. I fell apart completely shortly before my university finals. And then I was told that the problem was my personality.

In a perverse sense, I am lucky: I live in an area where this insult at least functioned as a passport to therapy. Even so, I have had my diagnosis used as an excuse for neglect when suicidal. The manager of my crisis team told me that people with “BPD” say they are suicidal in order to access services – a rehashing of the old jibes “attention-seeking” and “manipulative”. I have had my pain and anger, caused by the distressing environment of a psychiatric ward, turned against me as a symptom of my own disorder.

I write this thinking of my friend JL, a mental health blogger whose “borderline personality disorder” label led to nothing but contempt and rejection from mental health services until her death late last year. She wrote, “for me EUPD [...is...] A diagnosis resulting in stigma from staff and a judgmental attitude… Even my access to A&E has been affected as I’m told that I can’t turn up there ‘just because you are feeling suicidal’.”

Even once I was given a diagnosis, I had to prove I was disordered just the right amount to access therapy – in the increasingly narrow zone between “beyond help” and “not in need of it”. I think of it as Goldilocks and the Three Therapists.

The subtitle to Tyrer’s book is “shredding the stereotypes of personality disorder”. I no longer believe this is possible while psychiatry and psychology have licence to talk about us in these terms, yet fail to acknowledge the structural inequalities reflected in their diagnostic criteria. My personality is who I am. You cannot tell me my very self is disordered and then convince me you do not want to reduce me to a stereotype.

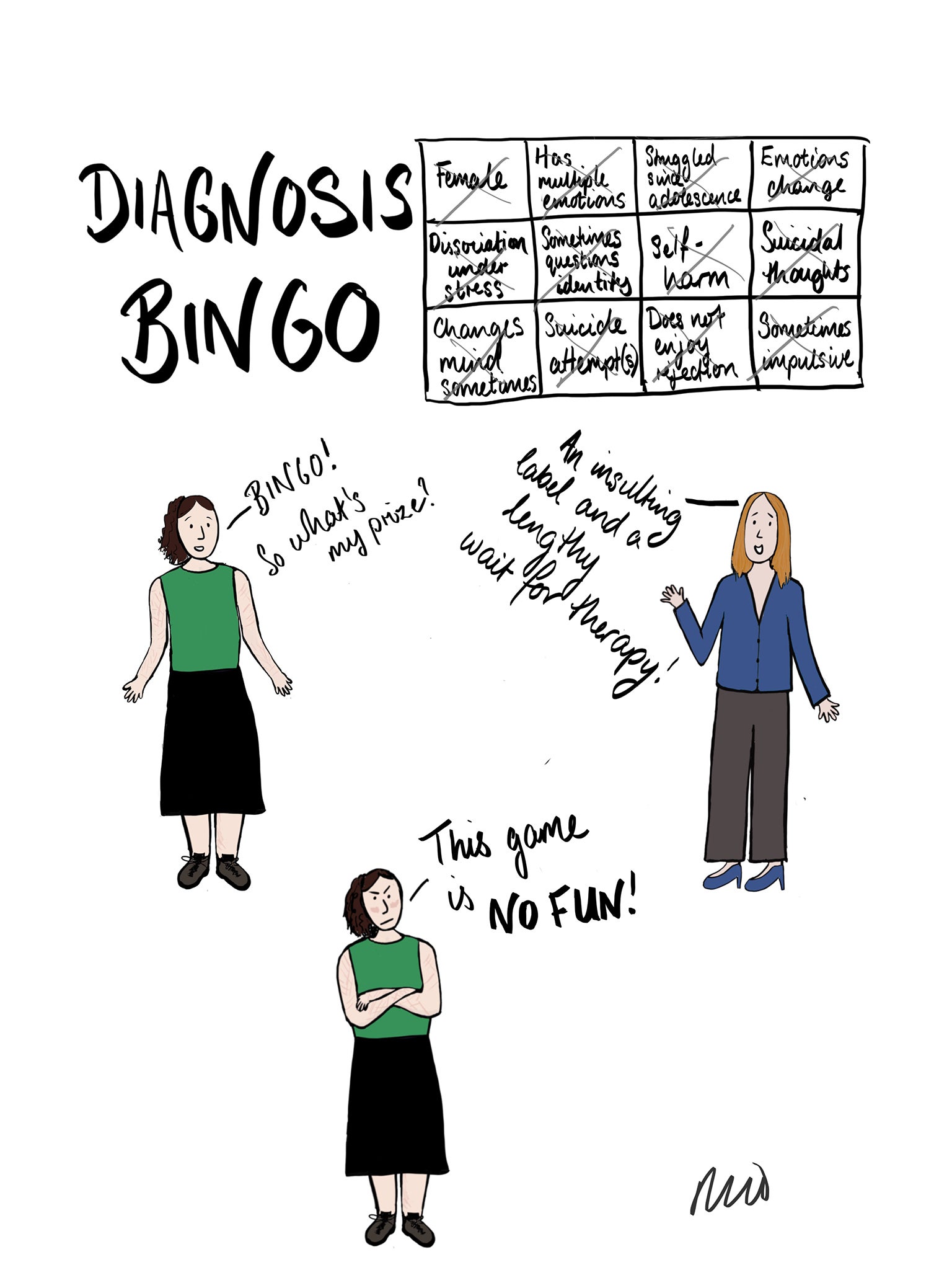

Those of us who live with this label can speak for ourselves. Many of us reclaim some power over our identities through humour – such as this satirical guide to avoiding a diagnosis of “personality disorder” written by activist collective Recovery in the Bin.

My bitterest experiences often become my funniest cartoons. Some also campaign and support each other through organisations led by lived experience experts, such as the National Survivor User Network.

Tyrer is not speaking for the people he aims to help – he is speaking over us. I want everyone to know that sometimes when people roar, it is not because they need to be tamed but because they need to be heard.

Rachel Rowan Olive is a writer and illustrator. If you have been affected by this article, you can contact the following organisations for support:

mind.org.uk

beateatingdisorders.org.uk

nhs.uk/livewell/mentalhealth

mentalhealth.org.uk

samaritans.org

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies