As a former government adviser, I’m seriously worried about Boris Johnson’s attitude to racism

When he came into power, I heard that he only wanted people who were ‘demonstrably his’. Soon after, the race equality agenda came to a grinding halt

My time as the (fiercely) independent chair of the Race Equality Unit Advisory board is over. My last official task was last month when I met with the new Race Disparity Commission team, which Boris Johnson set up in the summer, and its new chair Tony Sewell. During that meeting, I made very clear the priority for the government to immediately establish a Covid-19 Race Equality Strategy to deal with an imminent Covid-19 second wave, an unprecedented raft of redundancies and the further widening of the education gap, all of which disproportionately affects black, Asian and minority ethnic groups. The challenge for both the new commission and the government is the need for race policy action right now – a test as to whether they truly believe the challenge to confront systemic racial inequality is as deep and wide as it really is.

More on that meeting in a moment.

First, a reflection about the establishment of the Racial Disparity Unit and the Advisory group that I chaired, and why a race champion is so desperately needed right now.

I had put the idea of a Race Audit to Theresa May’s special adviser, Nick Timothy, when they were both at the Home Office. They liked it, but it got kicked into the long grass because the then prime minister David Cameron wanted his vacuous “End racism by 2020” to be centre stage. I know it was pretty much gesture politics because when I went to see a Downing Street official to talk about it, he said, “Don’t get too excited, there’s really not much to it.”

But when May did come into power and spoke about “burning injustices”, the audit was back in the game, only bigger. The audit or Racial Disparity Unit as it would be named, would look at key aspects of our lives and lay bare racial disparities, or what the prime minister would describe as “uncomfortable truths”.

Every minster was given the brief once the data was there to see: explain the disparities or find policy solutions to change them. We had three priorities: employment, education and criminal justice.

My question to the PM was what happens when you’re not in the room, which I guessed would be often given that Brexit was sucking the life blood from national governance. She asked, "What do you suggest"? I said, we need a race champion, and it could be me!

The deal was done. Well, almost. As a non-party political activist, I told senior people in No 10 that the government had to show it was serious. On the day the unit and my advisory group was launched, the PM announced a £90m fund to get disadvantaged and Bame groups back intO work.

I met with cabinet ministers and senior civil servants, nearly always with Nero Ughwujabo, the first black special policy adviser to a prime minister. We set up a review about black school exclusions, we demanded the mental health review has race inequality written large. We called in the vice chancellors from the top universities. We demanded that officers get on with implementing David Lammy’s review. Every week, we brought people from various black, Asian and minority ethnic groups into Downing Street. “This is your house too,” Nero would say.

But our influence didn’t last long. As power ebbed away from the then prime minister, the backstabbing never ceased: ministers no longer felt the need to dutifully obey. One of our flagship policies trumpeted by May was the requirement to report discrepancies in ethnic minority pay. It was ready to go, but ministers dragged their feet, and the policy document sits gathering dust in the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, with, apparently, little or no interest from No 10. The other two big policies gathering dust were to twin university funding with the Race Equality Charter, which is a university policy framework that would help transform the Bame attainment gap, the lack of black professors, senior staff, and bring the curriculum into the 21st global century. And the last big idea we had was to recruit a modest 30,000 black teachers over a 10-year period. The ideal number needed would be 50,000.

When Johnson came into power, having ousted May in a Brexit coup, no one from his inner circle directly contacted me. But I was told through the political grapevine that there was “good news and bad news”: The good news was that the future for the Race Disparity Unit was looking good. An early sceptic of the Unit when it was launched in 2018, Munira Mirza, now head of policy at No 10, had had a change of heart, and had decided that an evidence-gathering unit could be useful; but the bad news for me was that the PM only wanted people who are “demonstrably his” to be involved with this government. Which I read as, “so, absolutely not you”.

I was fine with that, that’s politics. But I worried that the race equality agenda would come to a grinding halt.

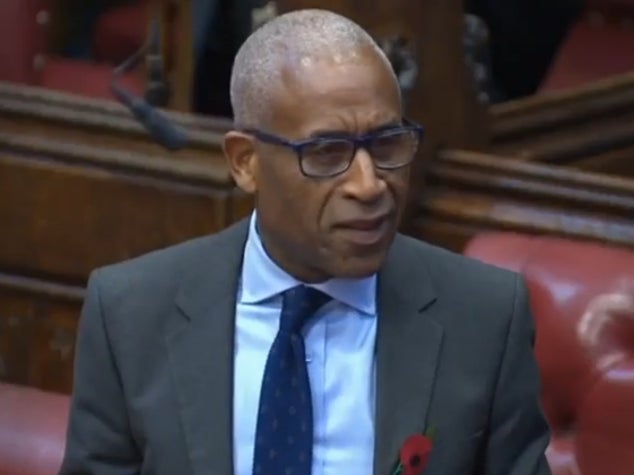

For the best part of six months, it was left in limbo, including the advisory group, until the government announced its successor, the Race Disparity Commission, headed by Dr Tony Sewell. For some in the black community, alarm bells started to ring.

More issues arose when the prime minister announced the body, stating in regard to race equality that we must “change the race narrative” as well as the notion of “victimhood”.

If I was in any doubt about this potentially dramatic shift, I soon wouldn’t be. During that handover session with the new commission, its chair told me, “we really have a problem with the prevailing narrative”. In a testing session I informed the group that you change the narrative by transforming the systems of inequality, not the other way around.

But the other huge concern is that the commission will not report its recommendations until either December or January. That’s in two or three months.

The few things we do know about the pandemic and Covid-19 is that it waits for no one and above all has an ability to target societal structural inequalities. So, as some have wrongly suggested, this virus does not target a race of people or their ethnicity but it will exploit aspects of society that can be best described as racialised: areas of within our society where systemic racial inequality persists. For example, low paid and those on zero hour contracts, essential or frontline workers who are overly exposed to the virus, including nurses, care-workers, porters, security guards, and cleaners are overrepresented by these individuals and therefore have died in greater numbers.

Furthermore, the imminent economic downturn through the chancellor ending the furlough scheme could mean tens of thousands of redundancies. Many will be already on low pay, zero hour contracts, especially in the hospitality sector, which again is often dominated by workers from black Asian and minority ethnic backgrounds. The other impending challenge is within education. The National Foundation for Education research stated last month as a result of the Covid lockdown, Bame pupils will need a more intensive catch-up than their white peers.

The overall challenge is a stark one. Lives could be needlessly lost, poverty levels could skyrocket, and a generation of young pupils’ futures are in serious danger.

The government must have a policy plan now, not in December or January.

There are two key areas that the government could enact without delay. First, it needs to implement the recommendations from the dozen or so race equality reviews over the past five years, including the Lammy Review, the McGregor Review, the Bame Covid-19 Review and the Windrush Review.

Secondly, as a matter of grave urgency, the government should put together a Covid-19 race equality policy document that begins immediately to protect lives, mitigate wholesale redundancies and ensure students don’t fall off the educational cliff.

In the medium and long term, if the commission abandons its fixation around the “narrative”, it could offer solutions that help us to dramatically reform our institutions in a way that could deliver greater race equality for generations to come. The whole of society gains by delivering such equality. Let’s not forget that.

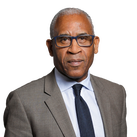

Simon Wolley is director and founder of Operation Black Vote as well as former Advisory Chair of the government’s Race Disparity Unit

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks