Kenyan schools adopt environmental education

Over 170 schools near critical Mau Forest have incorporated a tailored curriculum to teach children about environmental conservation

More than 170 schools bordering major water towers in Kenya have adopted a tailored syllabus that integrates conservation in the usual curriculum. The move is meant to conserve the water towers.

The schools bordering Mau Eburu, South West Mau forest, Aberdares and Mt Kenya forests incorporate the pioneering syllabus that covers soil conservation, water, pollution, tourism, and environment in addition to the Competency-Based Curriculum (CBC).

“When CBC came in place, we had already designed the curriculum and it was being piloted in schools. The conservation curriculum had exactly what was in some subjects under CBC,” said Alfred Orina, Chair of the Teachers’ Implementation Committee.

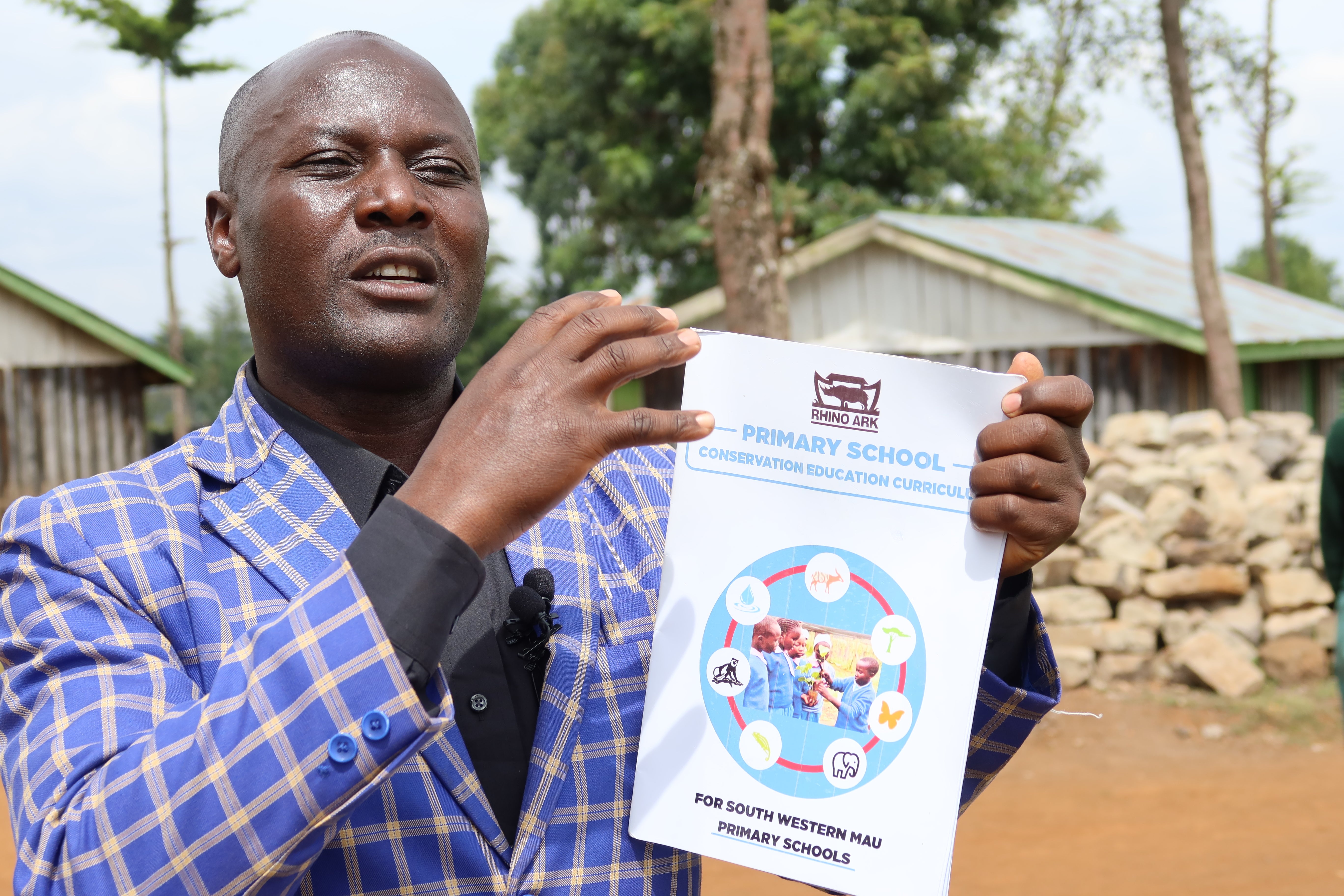

Dubbed ‘Conservation Education Curriculum’, the programme started in 2018 following development of the curriculum under a public-private partnership between Rhino Ark, and the Ministries of Environment, Education, Science and Technology.

171 schools are enrolled in the programme, from different areas across the Mau Forest Complex, which spans 273,300 hectares and is the largest indigenous montane forest in East Africa. The curriculum is, however, different across the water towers.

In schools bordering the South West, for example, the curriculum concentrates on the forest blocks within the area, highlighting the challenges, the wildlife found in that area and what can be done to address the challenges.

In schools around Eburu Forest to the east, learners are taught about endemic wildlife. They also learn about challenges such as charcoal burning, logging, hunting and how they can stop or reduce it.

In Mt Kenya and Aberdare, learners are taught about tourism and endangered wildlife species, and possible solutions.

“While undertaking their practical sessions, the learners tend their own tree nurseries and plant trees in part of the degraded areas in the forest,” Orinda said.

The curriculum starts off from Standard Four in primary school and continues to high school. Grade Four learners are widely taught about water. The topic is diverse and covers sources of water, the importance of wetlands and why they should be conserved.

In Standard Five, the syllabus is purely on wildlife, where learners are discouraged from hunting, while in Standard Six, they are taught about soil, topics that touch on degradation through poor farming practices, and charcoal burning.

In Standard Seven, the pupils learn about the environment in general and in Standard Eight they are now trained on forestry.

In secondary schools, the topics are similar but more in-depth, and also incorporate practical sessions. While there are no examinations on the curriculum, Orina said the learners are assessed through projects. The lessons are also taught alongside other topics seamlessly.

“We integrate the lessons seamlessly because it is almost the same thing. We have environmental classes which are just a replica of this and to assess their understanding, the teachers gauge it through practical, oral lessons and demonstrations. We have these projects on Wednesdays and Fridays after classes,” Orina explained.

Adopting the curriculum, he says, has seen schools come up with projects like water harvesting, tree nurseries and many have also adopted energy-saving ideas.

Cynthia Chepngeno, a pupil at Kures Primary School, says besides the curriculum equipping them with knowledge on their ecosystem, it has also earned them revenue from projects.

“We sell trees to state agencies and corporations who want to rehabilitate the forest. In doing so, we earn some money which we use on projects. The last time we sold the seedlings, we raised Sh2,500 (£16) which we spent on storybooks. Previously, we got money which we channelled to our school lunch programme,” Chepngeno said.

Isaac Kiplang, a Standard Seven pupil, said besides restoring the forests through planting trees, they also learn about different animals within the South West Mau and why they should be protected.

“Initially, we thought it was normal and fun to go hunting as boys but we do not do that anymore because we want to protect our wildlife,” Kiplang said.

Alphonce Rotich, an official with Rhino Ark in South West Mau, said the curriculum was developed with stakeholders and experts drawn from Kenya Wildlife Service, Kenya Forest

Service, National Environmental Management Authority (NEMA), Nature Kenya, Wildlife Clubs of Kenya, Ministry of Education, teachers and conservationists.

“We want the learners to be part of the rehabilitation and conservation process. We wanted them to be aware of their surroundings and why they are in a unique environment. As learners surrounding these water towers, they have the privilege to be involved in the conservation process,” Rotich said.

The programme also trained teachers who would take the learners through the curriculum. In South West Mau alone, 98 teachers were enrolled to the curriculum, which has since been launched at the Sub-County level.

This article is reproduced here as part of the Space for Giants African Conservation Journalism Programme, supported by the major shareholder of ESI Media, which includes independent.co.uk. It aims to expand the reach of conservation and environmental journalism in Africa, and bring more African voices into the international conservation debate. Read the original story here.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies