Care about poverty and inequality? Then you must give credit to tax credits

It has been predicted that there will be an immediate 200,000 increase in the numbers of children living in poverty if the Government's cuts to tax credits go ahead

The Victorian historian JR Seeley famously suggested that Britain acquired its empire in a “fit of absence of mind”. The Government likes to argue that today’s tax credit empire grew in a similar unplanned fashion.

In his summer Budget speech George Osborne complained that the national bill for these benefits has spiralled from £1bn when it was introduced to £30bn today. He argues that Labour, which bolstered the scheme inherited from the Tories in 1997, never intended it to sprawl to such bloated proportions.

That may, or may not, be true. But let’s consider what would have happened if Labour hadn’t overhauled and expanded the income support system in 1999. Thanks to the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), we have some estimates.

Labour made a decision to target families with children through the expanded programme, with the explicit goal of slashing child poverty rates. And there was clear success in this respect. Child poverty, defined as the number of children living in households with an income below 60 per cent of the median, fell from 26 per cent in 1997 to 18 per cent in 2010. The ambitious target Labour had set itself of halving the rate was missed. Yet the progress was nevertheless substantial.

Moreover, the IFS’s estimates suggest that if the old benefit system inherited from the Conservatives in 1997 had remained in place, child poverty would have risen to 31 per cent. There were 13.2 million children in the UK in 2010/11. So without Labour’s tax credits, 1.8 million additional children would have been in poverty in 2010. That’s the counterfactual that critics of tax credits must address.

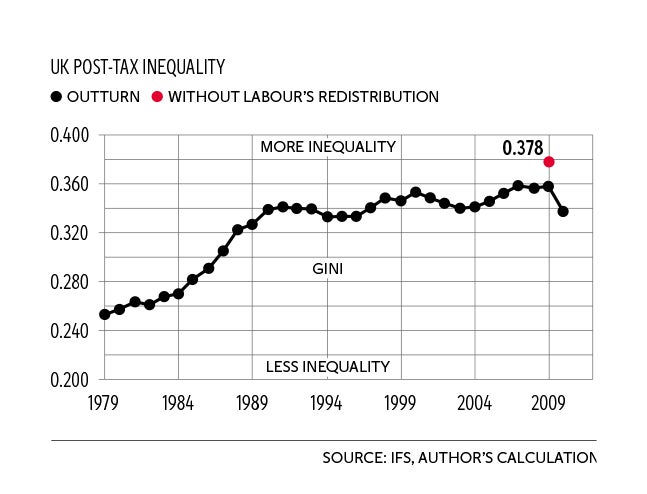

IFS research shows that overall income inequality would also have increased without Labour’s tax credits and its other new benefits targeted at reducing pensioner poverty. Some commentators, keen to push back against the rising tide of concern about the skewed distribution of rewards in our economy, point out that inequality, as measured by the Gini co-efficient, has actually been flat since the late 1980s. So why, they ask, all the fuss about inequality?

It’s true that the Gini hasn’t budged significantly since Margaret Thatcher left office in 1990. But that’s largely because of Labour’s redistribution system, which has been like a fire hose trained on the forest fire of inequality. The system has managed to keep the fire contained (at least beyond the very top of the income distribution). But the system needs to spray out increasing volumes of water to do the job. Hence the fast-rising tax credits bill. It’s intellectually dishonest to point to the benign overall inequality trend under Labour as a sign of the egalitarian nature of free markets while failing to acknowledge the redistributive policies that have delivered the stabilisation. If you care about inequality, you should give credit to tax credits.

David Cameron claims to care about it. In his 2014 party conference speech, the Prime Minister boasted that inequality rose under Labour and fell under the Coalition. It was a cheap point: the Gini ticked up very slightly between 1997 and 2010. But the greater cheek was that the Prime Minister failed to acknowledge what would have happened to inequality without the tax credits system that his government now plans to slash.

That impact will be made plain if the Treasury does follow through on its plans to make these savings. The Resolution Foundation think-tank has predicted an immediate 200,000 increase in the numbers of children living in poverty due to these cuts. And some fear that all the gains made by Labour in curtailing child poverty are going to be reversed over the next five years.

But are tax credits part of a more general problem? Some argue that they are partly responsible for the underlying trend of rising inequality because they subsidise employers, enabling them to pay lower wages than they otherwise would. This is a line that was repeatedly brandished in last week’s House of Commons debate on tax credits – and it’s a criticism that’s sometimes voiced by people on the left who would normally be sympathetic to redistribution.

It’s a misguided criticism. Research suggests that tax credits have not put downward pressure on wages. Nor is there evidence that they create a disincentive for people to take up work. Indeed, the evidence suggests that the system has encouraged more people into jobs, particularly single parents. Labour’s tax credits did weaken the incentive for couples with children to have two earners rather than one. And they did result in high marginal rates of taxation on extra income for a relatively large number of recipients. But these effects are an inherent property of any means-tested redistribution system. The only feasible goal is to minimise the disincentives, rather than eliminate them altogether. An objective look at Labour’s tax credits suggests a pretty good balance was struck.

There are certainly problems with the structure of our economy, which redistribution alone cannot solve. There’s not enough training and investment in human capital by firms. This hinders the productivity development of workers and the wages they can command. Employment growth in recent years has also been skewed towards relatively low productivity jobs, such as shop assistants. It’s welcome that the present government says it wants to address these causes of low pay directly. And there is a respectable economic case for the Chancellor’s chunky increase in the minimum wage. Median wages stagnated from around 2003, even while the economy was still growing strongly. It’s undoubtedly a problem that tax credits were necessary to make up the shortfall and that so many working people in receipt of tax credits remain on the cusp of poverty. But ministers can address these fundamental problems without dismantling tax credits.

Cameron and Osborne talk of “low wage, high-welfare” as if one leads to another, implying that cutting welfare will help to push up pay. But this is mere rhetoric, designed to provide cover for their chosen cuts to public expenditure and their chosen timetable to achieve an overall budget surplus.

“Those who oppose any savings to tax credits will have to explain how on earth they propose to eliminate the deficit,” said the Chancellor in the summer. Simple: close the deficit more slowly. The sky will not fall in if there is no absolute surplus in 2019-20 – a date Osborne has fetishised. Decent growth will take care of the deficit. And let ministers – and indeed all of us – think more deeply about how to lift the wages of the least well-off so that the tax credit bill can fall organically and without cuts pushing more working families into poverty.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks