The Weasel: The fat of the land

By Christopher Hirst

A laid-back sort of dude, I don't get het-up about American annexation of the English language. I am amiably disposed towards heist, feisty and hike (as in price increase, not walk). My blood pressure does not rocket too radically when people pronounce schedule as skedule, spell programme as program or kick ass rather than arse. I even manage to withhold an Anglo-Saxon retort when presented with incomprehensible metaphors about "reaching first base", "not playing softball" or "ballpark figures". But when America attempts to exercise its hegemony over the English dumpling, I say enough's enough.

My doughty outburst is prompted by a doughy volume from the US. With the exceptions of Gormenghast and Lady Chatterley's Lover, I cannot recall any title that promised so much but delivered so little as A World of Dumplings by Brian Yarvin (Countryman Press, £15.50). At least, this is the case with the section devoted to British versions of this transglobal delicacy. Mr Yarvin's book is fine if you want to know about such specialities as xiao long bao (Shanghai-style soup dumplings), gnudi con zucca (cheese and pumpkin ravioli without the pasta) or vuska (Ukrainian folded dumplings whose name "comes from their resemblance to a certain feature of a cat's anatomy").

However, there's a shock in store on page 216, where the British chapter starts. Mr Yarvin describes our main contribution to the World of Dumplings as "something more home grown than burgers or pizza but still with a touch of the exotic". This, you'll be astounded to learn, is the Cornish pasty. Bizarre. Even Mr Yarvin admits it's an odd inclusion: "Aren't these pies? Still, they're wrapped in dough... and therefore you'll find them right here." Continue this weird tour d'horizon of the British dumpling and you'll find that our other great offerings in this field are the "traditional beef and turnip pasty", the vegetarian onion and turnip pasty and the mild curried lamb pasty. Mr Yarvin reveals his perplexity with British cuisine in an aside on mushy peas: "not mushy and not exactly peas".

Though it's scarcely conceivable, the real traditional British dumpling does not merit a mention in A World of Dumplings. It's like Hamlet without the Prince. Bobbing on the surface of a stew, these gravy-tinged clouds of delight draw cheers from any right-thinking Briton. Like oxtail stew, it is one of those dishes that make you wish it were winter all year round. The main reason for Mr Yarvin's strange omission is that Americans are strangers to suet. Or almost. You will find an American "Suet Page" on the web, but this turns out to be part of the Baltimore Bird Club website. In America, suet, which is the hard fat found around ox kidneys, goes on to bird tables not into dumplings. For his Quebecois apple dumplings ("an intensely English recipe"), Mr Yarvin advocates the use of lard, which he obtains from "the freezer case of a local Chinese supermarket".

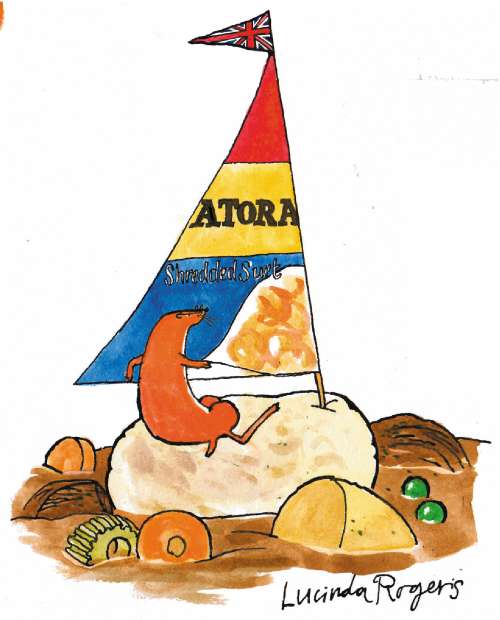

It is primarily due to a Mancunian printer of French birth called Gabriel Hugon that we continue to consume suet. Observing his wife hacking at a huge lump of suet, the idea for one of the world's first convenience foods occurred to Monsieur Hugon. In 1893, he opened a factory selling refined shredded beef suet. Sold in tricolor-coloured boxes, his bovine product was named Atora from the Spanish toro. Now based in Hartlepool and owned by Premier Foods, the Atora factory produces 2,300 tons of suet, both beef and vegetable, per year. In a slightly daunting calculation, the company estimates that this is "enough for 1 million dumplings a day". In an attempt to expand its applications, Atora has issued a cookbook called Not Just Dumplings. If the citizens of the US were to catch a whisper of such suet-enhanced temptations as date citrus spotted dick, savoury Eccles cakes or roast curried cod with savoury dill dumplings, there can be little doubt that a mighty clamour would arise from across the Atlantic: "Americans demand Atora! We'll sue for suet!"

However, these dishes are the tip of the iceberg in suet cuisine. I happen to be the proud owner of an earlier booklet from Atora (undated but it looks to come from around 1960) that offers a wonderful suetty smorgasbord. In the savoury dept, it suggests such toothsome, Atora-enriched items as tongue rolls, liver-and-rice mould and, for a special Christmas treat, giblet pudding. Traditional dishes include Buckinghamshire dumpling (stuffed with liver and bacon), Cotswold dumplings (grated cheese) and the irresistibly alluring Sussex blanket. On the dessert trolley, Atora is an essential ingredient in apricot delight, chestnut meringue pudding and rice croquettes ("when cold, form into attractive shapes").

In the final section, "Sundries", a whole new world of possibilities opens up for suet lovers. When making porridge, we are urged to "add a teaspoon of Atora for each person". This amendment "gives a marked improvement in flavour". If we include a tablespoon of Atora with a pint of milk when making rice pudding, "immediately, you will notice the difference". Remarkably, the use of suet is not limited to gastronomy. "A teaspoon of Atora, taken in a glass of hot milk at bedtime is a very soothing and beneficial treatment in the case of a cough or sore throat." It is also "definitely beneficial in all cases of catarrh, chest or bronchial troubles". Since Mrs W happens to be burdened with a troublesome cough, I suggested this sure-fire panacea. Inexplicably, she turned me down like a bedspread. I blame America.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks