Bernanke is right to dash the expectation that ‘tapering’ is going to happen any time soon

The US economy isn't out of the woods yet, as a look at the labour market shows

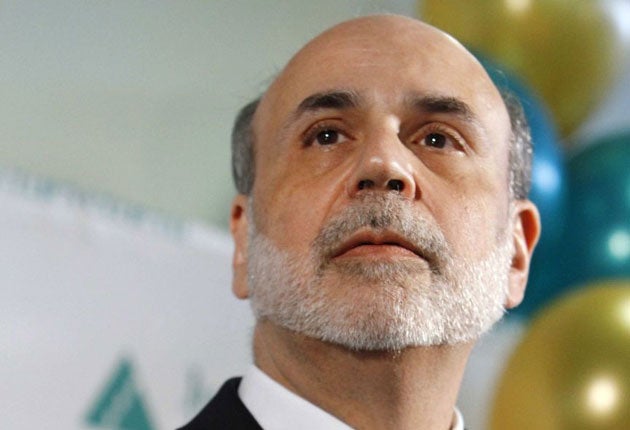

The International Monetary Fund and the US Federal Reserve both gave us a much-needed reality check this week. The IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook cut its forecast of world output in both 2013 and 2014 by 0.2 per cent to 3.1 per cent and 3.8 per cent respectively. And the Fed’s chairman, Ben Bernanke – as predicted here a few weeks ago – brought over-exuberant markets to their senses, ending the bond market rout that kicked off six weeks ago.

The message is that the US economy is nowhere near out of the woods – and we only have to take a look at the labour market to see that.

I was amused by the positive coverage surrounding the IMF’s upgrade of its UK GDP growth forecasts from 0.6 per cent in 2013 to 0.9 per cent, whilst keeping its forecast for 2014 unchanged at 1.5 per cent. For the slashers in Downing Street that shouldn’t be too much of a cause for celebration: the IMF forecast of growth of 2.4 per cent across 2013 and 2014 combined contrasts sharply with the Office for Budget Responsibility’s forecast in its June 2010 Budget forecast of 5.6 per cent. Even in March 2012 they were forecasting growth of 4.7 per cent. Furthermore, even if the IMF forecast is correct – and based on their past track record it may well be too optimistic – by the 2015 election year output would still be about 1 per cent lower than it was at the start of the recession in 2008. This would mean that George Osborne had overseen the weakest recovery that will have taken more than twice as long as occurred in the Great Depression, which was over in 48 months in output terms.

Mr Osborne still hasn’t told us what went wrong or what he would have done differently if he had known his policies would destroy growth and jobs.

The second big event was the publication of the minutes of the Fed’s June policy meeting, much awaited by some commentators who – wrongly, in my view – had anticipated tapering, or slowing, of quantitative easing in September. This was always for the birds given the state of the US economy.

There was some confusion because the minutes did suggest a substantial degree of conflict over the future path of monetary policy. The most telling part was this statement: “many members indicated that further improvement in the outlook for the labor market would be required before it would be appropriate to slow the pace of asset purchases. Some added that they would, as well, need to see more evidence that the projected acceleration in economic activity would occur, before reducing the pace of asset purchases.”

In my view “many members” refers to the majority and primarily the Big Five blocking coalition of Mr Bernanke, vice-chair Janet Yellen, William Dudley, Eric Rosengren and Charles Evans. In the US the chairman gets to decide what he wants – no minority voting here. This certainly doesn’t read like tapering given these members are looking for activity to accelerate in the same week the IMF downgraded their US forecast by 0.2 per cent in both 2013 (1.7 per cent) and in 2014 (2.7 per cent).

The key question is what has happened to the US labour market of late? Over the last three months, April-June 2013, employment, based on the household survey, is up by 480,000 (non-farm payrolls based on an employer survey are up 390,000). The table makes clear that over these same three months, despite the rise in employment, the number of unemployed is up by 118,000. The unemployment rate is also up to 7.6 per cent in June from 7.5 per cent in April, although it has come down from a year ago from 8.2 per cent. At the same time, the number of participants is up from 63.3 per cent to 63.5 per cent, which means that jobs are being taken by non-participants rather than the unemployed. The rise in the number of first-time unemployment claimants of 16,000 was further bad news. The Fed has made clear it would keep going with QE until the unemployment rate hit around 7 per cent and would keep rates at the zero-bound until unemployment was 6.5 per cent with inflation was no more than 0.5 per cent above target. The US economy is nowhere close to these gateways.

To put this in context, the single-month numbers for the UK are also presented – unlike the US which takes seriously collecting up-to-date monthly labour market data, we only have data through April for the UK. Over the last year, as well as the last three months, the unemployment rate remains stuck at 8 per cent, with the number of unemployed rising by 29,000 over the past year. Indeed, there is evidence now that the participation rate in the UK is falling as people withdraw from the labour force.

The most important event of the week though was Mr Bernanke’s lecture in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he and I are both research associates. Most notable was the question and answer session afterwards. He dashed the possibility of tapering coming any time soon.

Mr Bernanke gave us a timely reminder of the Fed’s dual mandate to pursue maximum employment and price stability. Unemployment of 7.6 per cent is a miss on maximum employment. And inflation of 1 per cent is below the 2 per cent objective – hence the need for easing. This comes in the context of fiscal tightening which the Congressional Budget Office expects to knock 1.5 percentage points of growth from the US economy this year. The chairman couldn’t have been clearer: “Putting that all together … highly accommodative monetary policy for the foreseeable future is what’s needed for the US economy.”

Mr Bernanke made it clear that the 6.5 per cent unemployment rate is a “threshold not a trigger” and there will not be an automatic increase in rates even when unemployment gets down to 6.5 per cent, which is a long way off. Instead it may well be some time after that before rates would rise.

Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England, is likely to follow suit in August, setting out thresholds for ending stimulus – especially when fiscal policy is likely pushing down so hard on growth. Ben Bernanke is the man.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies