Ebola virus in the US: How did the disease ever spread this far?

This crisis exposes the great fallacy of the West’s global development agenda.

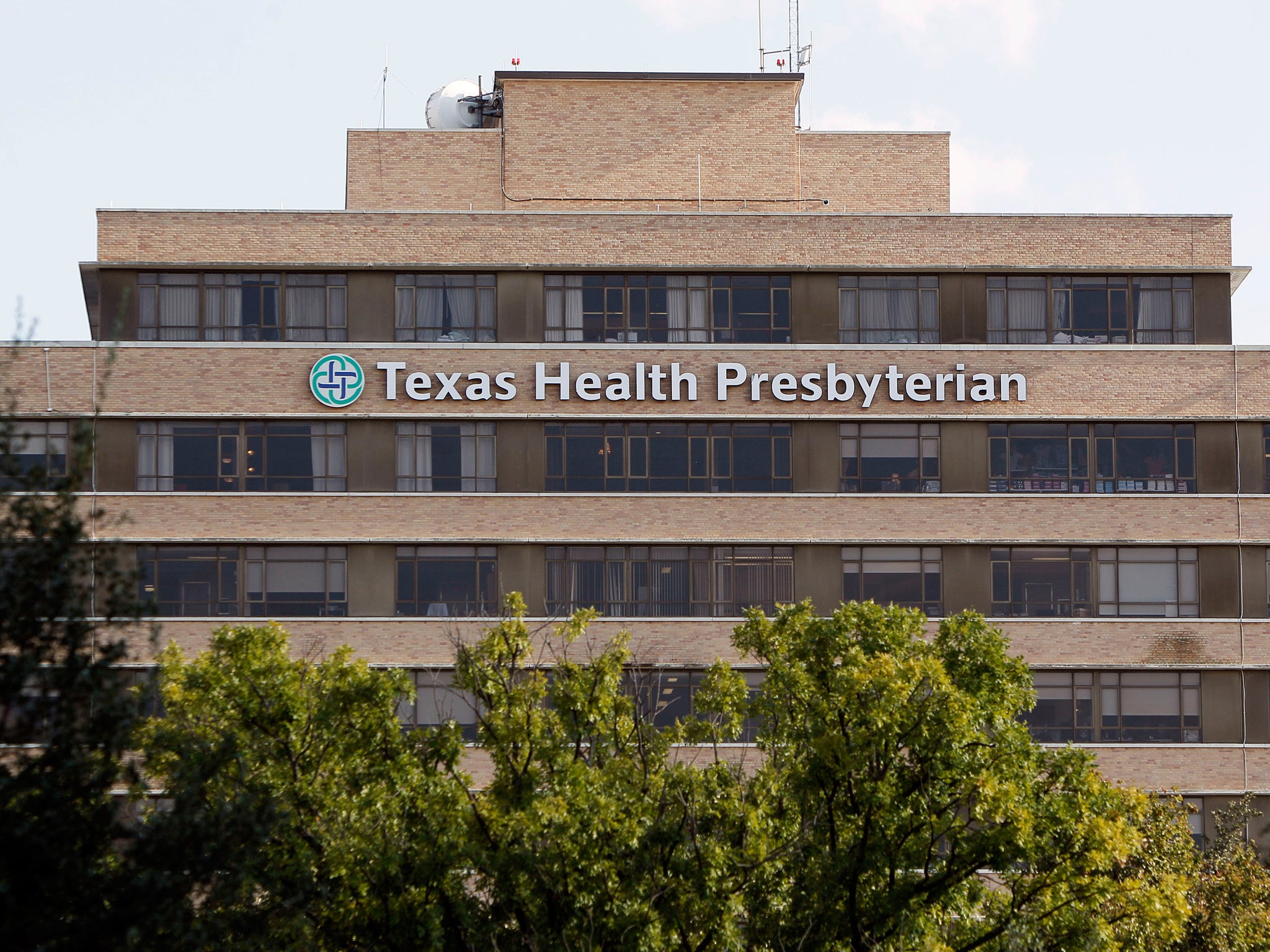

Confirmation of the first case of Ebola by the US Center for Disease Control (CDC) was accompanied by a telling message by its Director Tom Friedan “Ebola can be scary. But there’s all the difference in the world between the U.S. and parts of Africa where Ebola is spreading. The United States has a strong health care system and public health professionals.” The clear line here is ‘we got this’ in ways that African health systems don’t.

What this statement does not make clear is why West African health systems are struggling to cope with Ebola and how the international health community – including CDC– have contributed to this problem through a preoccupation with performance and prioritising specific diseases over investment in health systems.

Health systems – hospitals, clinics, procurements structures, research programmes, community health workers, training provision – are the first line of defence in the face of outbreaks such as Ebola. When that bulwark is breached so easily, as it was in Sierra Leone and throughout the region, it raises urgent and uncomfortable questions about the focus of our development priorities.

In fact, this crisis exposes the great fallacy of the West’s global development agenda. While the international health and development community in which USAID has played a leading role obsesses about technocratic development goals, targets, and indicators; the basic building blocks of health provision in poor countries have been desperately neglected.

There is a contradiction here. Isn’t it recognised that global health has done well out of the last 15 years of development spending?

This tide of resources, expertise and good will has led to a preoccupation with ‘vertical interventions’ – programmes that prioritise specific diseases such as Malaria. This is of course, not a bad thing in itself. Malaria is a scourge on the health and lives of Africans, and programmes to mitigate its transmission and effects are both vital and badly needed. I am not proposing that we cut off support for disease-specific programmes nor that development is a zero sum game - but our limited resources cannot ignore the less glamorous but no less urgent areas of clinics, hospitals and systems.

The singular focus on specific diseases, to the detriment of health systems, is a major reason why we are where we are in West Africa and presents a stark contrast to the rhetoric of contain and control presented by CDC in the US. The failure of the healthcare infrastructure to cope with Ebola in West Africa should not be a surprise; it is certainly not for those living and working in the region, many of whom have spent decades decrying the ramshackle state of hospitals, clinics and systems.

Will this failure cause a shift in our priorities?

The WHO has stressed the importance of health systems, and the World Bank began to make them the focus of its regional efforts a few years ago. Yet, the idea that health systems should be a key feature of the new Sustainable Development Goal process is gaining little traction in international development circles. In short, without a radical focus on health systems; the future is bleak.

The struggle to contain Ebola in West Africa and the confidence in the US shows how strongly equipped and fully-functioning health systems are fundamental to the management of health emergencies as well as the everyday health and well-being of people in vulnerable, poorer regions.

The stubborn focus on goals and specific diseases over the last fifteen years has led to a chronic and senseless neglect of health systems in developing countries. This focus has contributed to a catastrophic public health emergency. If we are to salvage anything from this human and regional tragedy, it should include a reappraisal of performance targets and disease-specific interventions and a commitment to invest money and expertise in regional health infrastructure in Africa. That, requires an urgent and radical shift in our accepted model of global health and development in which the US plays a crucial part.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies