Errors & Omissions: Between you and me, a lot of us mess up our pronouns

Inflection confusion, a bad case of reality and imprecise whales in this week's Independent

Several readers have written in about this puff from Tuesday’s front page, advertising an article inside the paper: “Why cheap oil should make you and I richer.” That should be “you and me”. Nobody would write: “Why cheap oil should make I richer.”

The personal pronoun, being the object of the verb “make”, should be in the accusative case. Putting “you and” in front of “me” makes no difference to that.

The trouble is that modern English has lost nearly all its inflections for case. (Modern German and Russian retain much more of the richness, in this respect, of ancient Indo-European languages.) In today’s English, apart from the possessive -s ending, there are only two cases, nominative and accusative. They appear only in personal pronouns in the first and third persons: I/me, he/him, she/her, we/us, they/them. That’s the lot.

The result is that English speakers are not used to dealing with case forms in a flexible, logical way. They tend just to extrude familiar clumps of words. And, of course, they have been taught from the cradle up never to say “me and my brother” (which is vulgar), but “my brother and I”. So they are not equipped to spot the times when logic demands “my brother and me”.

µ “Labour will call for an urgent statement into the agreement,” said a news story on Monday. “Inquiry into” is established style. In recent years we have got used to the “inquiry into” producing a “report into”, rather than “on”. And now we have a “statement into”. This is getting sloppy.

You can see that an inquiry passes into its subject like a probe or a knife blade laying bare the interior of an object. But what picture are we supposed to form in our minds when we read “a statement into”?

µ A Voices piece on Monday, criticising the British Empire, fell for the fatal charms of that slippery word “reality”.

“Our education syllabus focuses on imperial vanities, not realities.” Really? Writers love to accuse their opponents of ignoring “realities” – in this case presumably such horrible facts as the Amritsar massacre and the Bengal famine. But it is absurd to suggest that imperial “vanities” are not “real”.

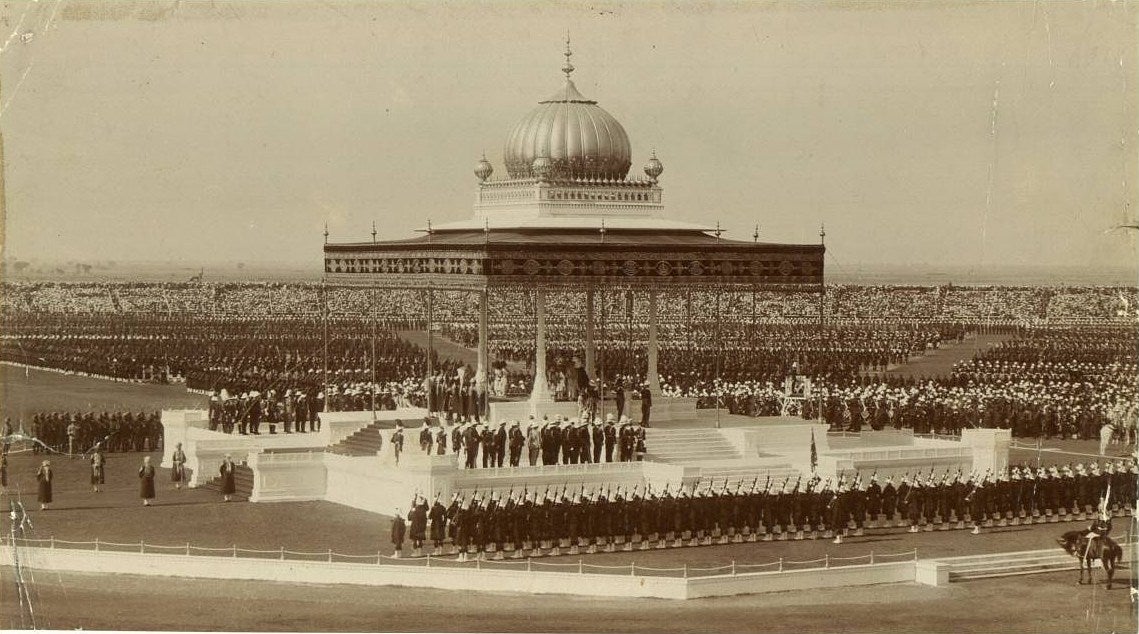

The Delhi Durbar of 1911 (above), for instance, really did happen. You may think such “vanities” absurd or immoral, but they are just as real as the massacre and the famine.

µ On Monday we reported on the beaching of sperm whales on the Lincolnshire coast: “The giant animals, which are up to nearly 15m long, attracted crowds of onlookers.” “Up to nearly” won’t do. “Up to” has a ring of precision, suggesting “thus far and no farther”. Then “nearly” makes it vague again. It must be said differently: “The giant animals, which can approach 15m in length…”

µ Our review yesterday of Spotlight, a new film about journalists, said of one character: “He’s the brow-furrowed, pencil-chewing exec.” Shouldn’t that be “furrow-browed”, as in “blond-haired” or “light-fingered”?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks