Faragemania simply cannot last - these European elections will be the crest of his power

An ideological vacuum gives space for populist to rise and appeal across the spectrum

The only surprise about the rise of Ukip is that anyone is surprised. The context in which party leaders make their moves is nearly always decisive. There is little that leaders can do about the wider background, and in this Thursday’s European elections David Cameron, Ed Miliband and Nick Clegg are trapped, while Nigel Farage is as free as a bird.

For once, the three mainstream parties are all contaminated by power, or perceived to be so. Labour ruled in the recent past and was in government when the economy crashed. The Conservatives and Liberal Democrats took over in 2010 and led the economy towards another recession. Even if they had not done so, voters would be protesting against a ruling government.

Normally, some of the protesters would support the Liberal Democrats. This option is not available to them as Nick Clegg’s party is in power. They might have voted for the main opposition party if it had ruled so long ago that they no longer felt angry about what had happened then. The Tory soundbite about Ed Miliband and Co crashing the car when they had the keys is one of the more accessible slogans, if simplistic.

Miliband crashed the car and handed the keys to Cameron and Clegg who crashed it again. Enter Nigel Farage.

Farage is the nice bloke who has never been an MP, let alone a ruler. He alone is uncontaminated by power. He enjoys adulation similar to that conferred on Nick Clegg at the last general election, but is currently even less constrained than Clegg was then. Clegg was a leader of a fully developed party and had to compromise in the build-up to 2010 in order to maintain unity. Farage happily disowns his party’s policies, candidates and the rest if they are inconvenient to him. He is a leader unconstrained by politics – a dream scenario.

In the 2010 election, Clegg was the fresh-faced outsider, the one who would save us from those hopeless orthodox politicians, who were all in it for themselves. Now Faragemania replaces Cleggmania.

Few listen to Farage very closely. There has never been a bigger gap between, on the one hand, political obsessives on Twitter who interpret every move, and, on the other, the majority of voters, who are indifferent to the twists and turns.

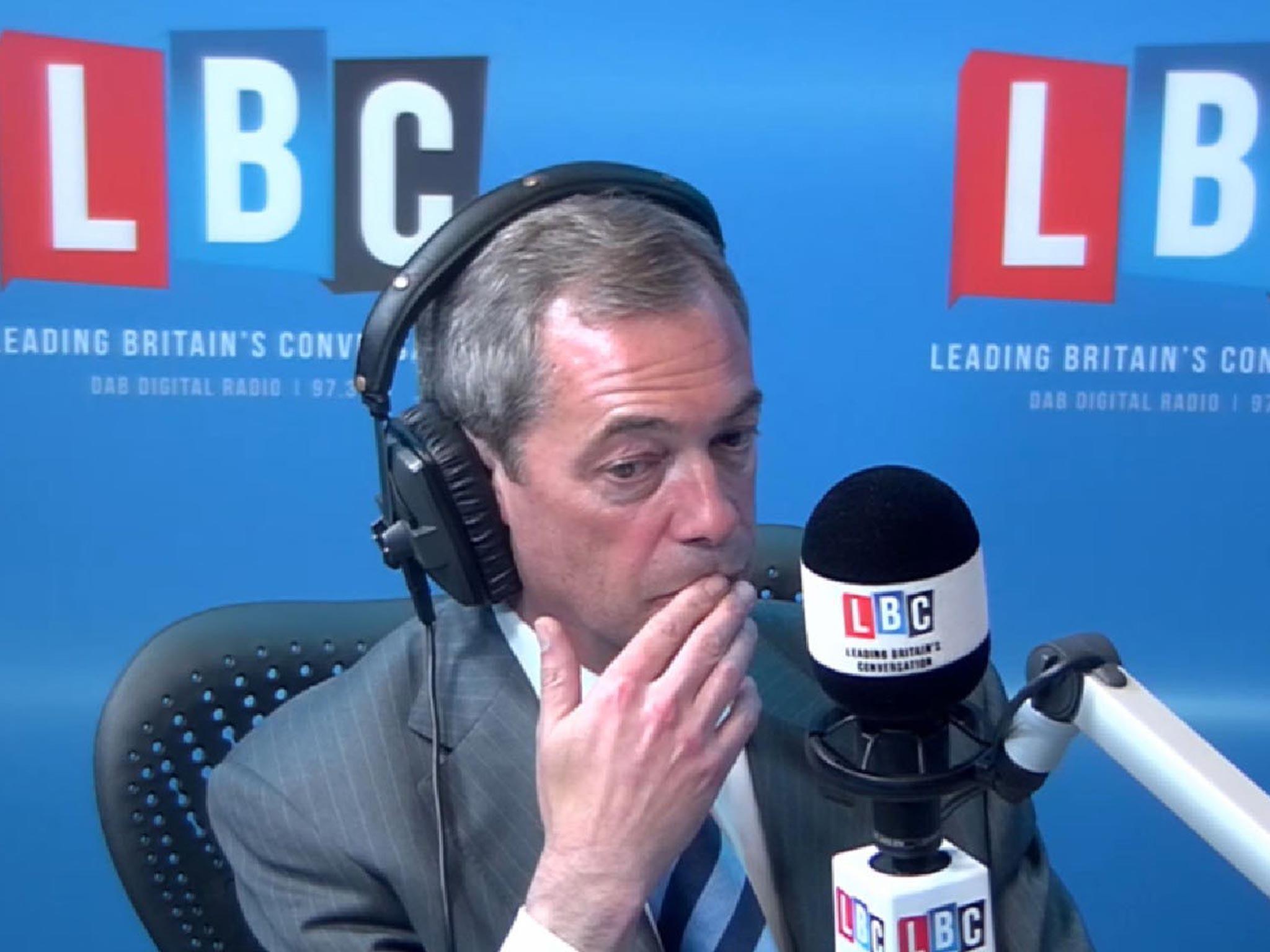

Those of us who follow politics closely wonder whether Farage will be damaged by his latest contortions. In an LBC interview last week the Ukip leader suggested he would be wary of living with certain Romanians as neighbours, but more relaxed if Germans moved in. Yesterday he placed a defiant advertisement in a newspaper, defending his comments.

Meanwhile, Ukip candidates make outrageous statements on a daily basis. In other parties such moments would lead to terminal crises. Farage ploughs on unperturbed. Whenever interviewers ask about comments from candidates, he shrugs them off with an almost endearing joke about all parties having their share of idiots. As far as his own comments are concerned, Farage moves on too. There he is, good old Nigel, speaking up for voters who are not listening very assiduously to the words.

Cleggmania lasted for a fortnight. Competing against parties with a recent governing past or ones that are in government now, Faragemania will last a little longer. Even so, these elections are the last that present Ukip with the perfect context. Soon the novelty will fade. Farage will be forced to make decisions about how his party fights the next general election, and the membership will come under closer scrutiny. He will become a more familiar political leader, dealing with dissenters, framing policy, answering to a wider programme. He will cease to be the wholly unconstrained outsider who has all the answers. Obviously this does not mean that the other parties can dismiss the discontent of voters. The 2008 crash exposed the weaknesses of assumptions that had shaped British economic policy since 1979. The subsequent recovery is fragile. There are huge regional disparities.

Senior figures from mainstream parties are nervous of stating clearly that there is a left/right divide. Indeed, some of them argue wrongly that there is no such division any longer. The ideological vacuum gives the space for the likes of Farage to rise and claim with some justification that he appeals to voters across the spectrum. As ever, there are big, complex challenges facing governments across Europe, with no easy answers. Individuals who appear to have easy answers flourish, but only fleetingly.

This week’s elections will be a very poor guide to what will happen in a year’s time at the general election. Dissenters from the three mainstream parties who panic will cause more damage to those parties’ election prospects than an increasingly exhausted, over-exposed, more politically orthodox Farage will be in a position to do.

Carney is right to worry about a housing market hangover

The Governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, worries aloud about the UK’s housing crisis. He has good cause to do so. We have been here several times before. The UK’s fragile economy recovers on the back of a house price boom in the South-east. In a single overheated region, property-owners discuss how much their homes are worth today compared with the week before. Younger people struggle to buy and can hardly afford to rent.

This happened in the 1980s and 1990s. In both decades governments sought to change rules to make it easier to buy homes rather than build additional properties. In both cases there were crashes, and some owners found that they owed more than their homes were worth. Here we go again. George Osborne’s help-to-buy scheme fuels the property boom. The boom generates another precarious recovery.

One of the curious trends in British politics is for economic mistakes to be repeated even though the ministerial policy-makers know the dangers. This happened with incomes policies and stifling corporatism in the 1970s, and now applies to the reliance on a property price boom.

There will, I predict, be another crash and that will be the last ride on this particular merry-go-round. In the end even these eerie repetitive patterns come to an end. No leader proposes an incomes policy now. After this election no leader will rely again on the huge unmet demand for property to re-heat the economy.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies