GCHQ can delete extremist content online all it wants, but it won't help defeat Isis

The head of GCHQ is wrong to blame tech companies for the rise of terrorist groups

Recent comments made by the head of Britain’s surveillance agency, Robert Hannigan, insinuate that social media companies are in part to blame for the ease in which jihadists and extremist groups use online tools to propagandise and recruit.

Not only is this line of thought misguided, but it remains counterproductive to focus security measures on censorship initiatives that, invariably, target a symptom rather than its cause. It is imperative that security services evolve alongside the rapidly changing threat.

Yesterday, Quilliam launched its new report, Islamic State: The Changing Face of Modern Jihadism, addressing the modernisation of jihadism by Islamic State (IS). Among other findings, our research showed that negative measures, such as blocking and filtering content, are often ineffective, if not counter-productive, in combating online extremism.

In our tracking of online accounts across various social media platforms, we witnessed constant take-downs and suspensions of jihadist and pro-Islamic State accounts. Like Twitter, most social media corporations have taken the initiative to suspend and take down accounts that contain explicitly illegal content, using guidelines that mirror European and UK Laws. Content take-downs are also conducted using user-generated flagging systems, whereby users flag content they believe to against the terms of use as laid out by the social media platform in question.

However, despite social media companies’ activism, this has is proven to be widely ineffective as a whole. One jihadist Twitter user has been seen re-establishing his 21st Twitter account, after having his 20 previous accounts shut down. Furthermore, within a short amount of time the user was able to re-amass over 20,000 new followers.

It is also difficult to broadly filter terrorist-related content, none-the-less ‘extremist’ content. Terrorist and ‘extremist’ material cannot be filtered through similar mechanisms as those used for Child Sexual Abuse Imagery (CSAI). While CSAI content is image- and video-based, the majority of extremist and jihadist online content is rhetoric, despite the more widely known violent images. For this reason, content must be overlooked reactively, rather than filtered pre-emptively.

Despite current efforts to take down pro-Islamic State content, censorship alone will never be the answer. Forcing social media platforms to require and hand over personal data for security officials, as called for by GCHQ, is also inefficient. As one online platform increases its censorship initiatives, or requests increased personal information, extremist and terrorist organisations simply migrate onto newer less restricted platforms. We have already seen this take place with jihadist discourses now taking place on alternative platforms such as Ask.fm, VK and Kik.

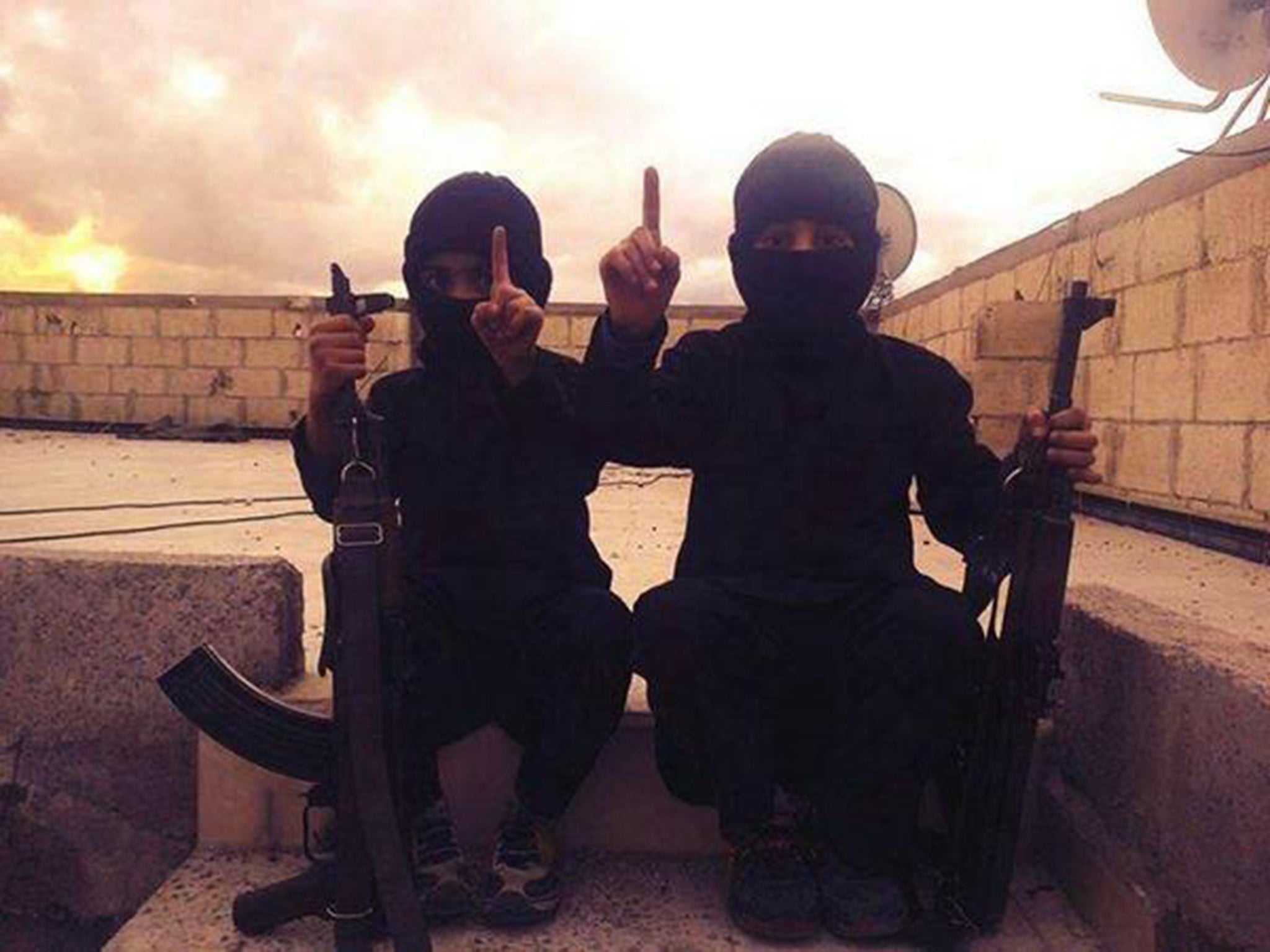

As fears continue to escalate over the unprecedented number of foreign fighters going to Syria and Iraq we need to come to terms with the real causes of radicalisation. When young Britons, Muslim or otherwise, feel that joining a violent terrorist organisation in a distant country is the best and most fulfilling life option for them, we have a problem that is much broader, with roots much deeper, than online content.

Islamic State has been highly successful in rejuvenating jihadism for a broader global audiences, facilitated by heightened tech-savviness. However, it is the nature of the propaganda that needs to be addressed. Both online and offline efforts need to be heightened to counter this propaganda. In the UK, and elsewhere, we have only just begun to see civil society and government initiatives aimed at countering and preventing the roots of extremism.

Young people need to be better trained in critical consumption skills in schools, (something just starting in the UK) so that extremist content is questioned, rather than accepted. Better communication within communities, religious circles and family units, discussing larger social and political concerns, such as the crisis in Syria and Iraq, should also be facilitated. Islamic State continues to win the propaganda game simply by being resilient, innovative and persistent. Surveillance, counter-terrorism and counter-extremism efforts should channel the same drive in promoting critical consumption skills and producing stronger counter narratives.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks