If Renee Zellweger wants to look different, who are we to question it?

The human face is a mystery we try to unravel at our peril

Renee Zellweger once served me canapés. I hope, at least, that I said “Thank you very much”. Under the sobriquet of “Bridget Cavendish”, the actor had dived deep undercover during three weeks as a publishers’ publicity intern to prepare for her uncannily pitch-perfect title role in the film of Bridget Jones’s Diary. No other member of the hawk-eyed media present at that book launch detected her either - even after her breakthrough performance in Jerry Maguire.

Ever since that evening - or rather, ever since I found out about its secret star - my admiration for Ms Zellweger has been tinged with a degree of awe. Here was a masterclass in method acting so flawless that no one even noticed it. How curious, then, that an actor repeatedly applauded for her chameleon powers should now attract a deluge of abuse when she decides to change herself.

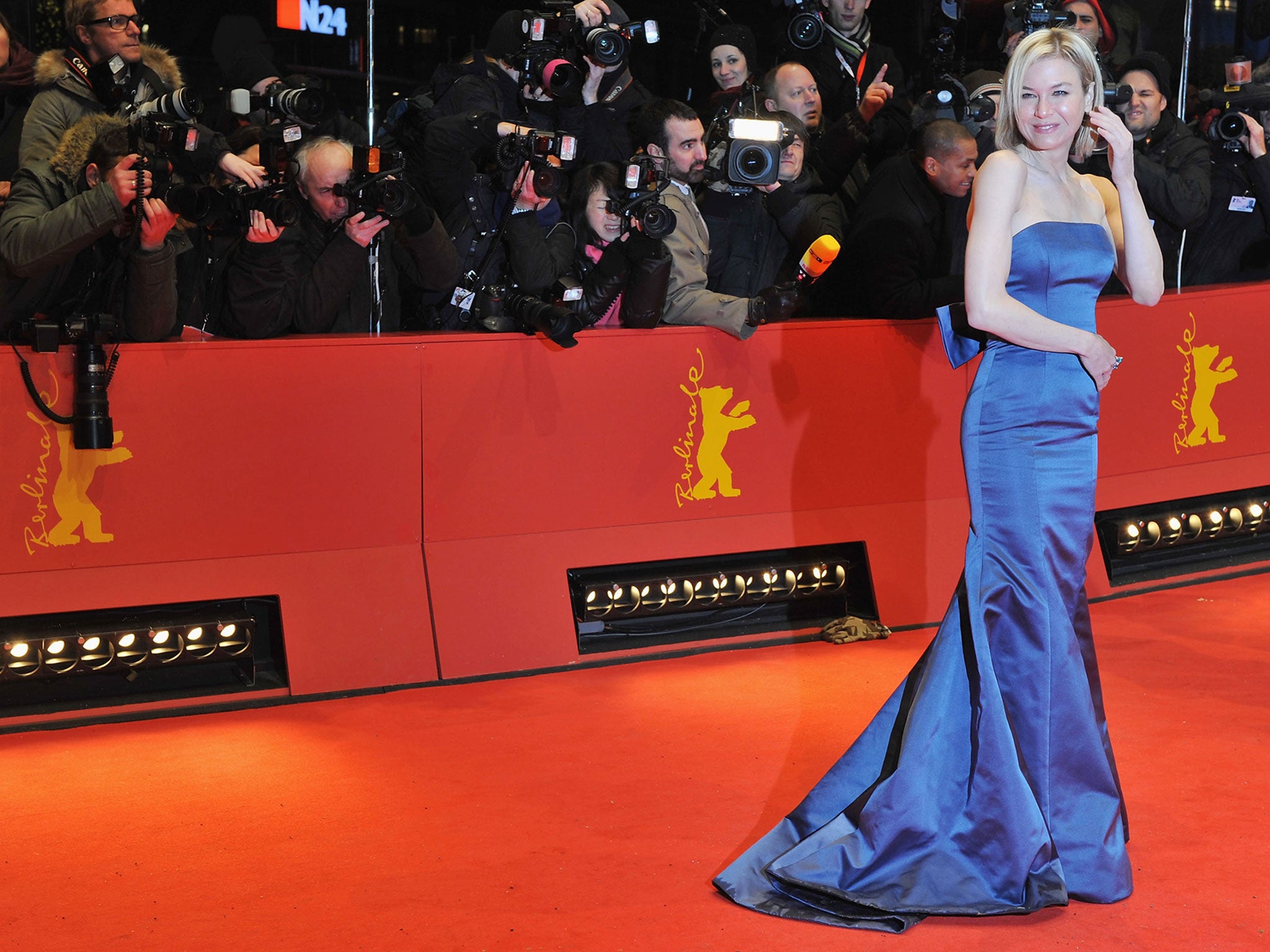

Zellweger’s New Face - that instantly-mythical artefact, first exposed to the lens at the Elle Women in Hollywood Awards on Monday - has already launched a thousand shits. Most of these malevolent snipers seem to believe that the public has or should have an absolute power of veto over the appearance of their favourite celebs. Stuff that for a game of soldiers, as Bridget (if not Renee) might say. For the actor herself, what matters is that “I’m living a different, happy, more fulfilling life, and I’m thrilled that perhaps it shows”. For me, the most painful aspect of this fiesta of spiteful innuendo has been to hear this smart graduate in English and drama defend herself with new-agey guff about “growing as a creative person and finally growing into myself”. Bridget might have managed a crisper “Naff off”.

Serious discussions about the perils of Botox, the ethics of cosmetic surgery and the pressure on women to stay young and beautiful have a place. Yesterday brought news that a British woman has died in Thailand after an operation to correct cosmetic surgery. But the Zellweger frenzy feels different: an atavistic outcry against the freedom to choose the face one shows to the world. Fans let their repressive instincts off the leash when, like border guards or secret agents, they seek to police the “real” visage behind an actor’s various personae.

Somewhere behind this furore lies a reflex puritan distrust of painted women. It could be that nips, tucks and fillers now occupy the place of shame that mascara or rouge took a century ago. The history of civilisation, however, is unambiguously on the side of face-sculpting slap. Make-up dates back to the earliest urban cultures. For the ancient Egyptians, kohl, henna and malachite came under the protection of the falcon-headed god Horus. Ever since, the universal quest for embellishment has gone along with an equally entrenched disdain for such artifice as a bid, sinful or futile, to defy the ravages of time. “Let her paint an inch thick,” as Hamlet - no stranger to misogynistic outbursts - snarls as he contemplates Yorick’s skull: “To this favour she must come.”

Theocracies such as Iran aside, the fight against women in warpaint was lost long ago. So the battleground of condemnation shifts. Now surgery - or, here, the mere imputation of professional “work” - counts as the ultimate hubristic denial of nature, truth and time. Since the 19th century, though, the moralist’s scorn has had a political dimension. When modern nations first began to photograph, fingerprint and measure their citizens, the policing of identity came to include the monitoring of appearance. Authority demanded to see, and to record, your one true face. Next time you step up to an e-passport scanner, read the rules to see how far the state still wants to register your unadorned features.

Supposedly, an open face reflects a clear conscience. Conversely, hair, hoods or veils mean that the bearer wants to hide. In the interests of transparency and equality, France has since 2010 outlawed the wearing of full-face veils - or any garment that “disguises the face” - in public. This month, singers at the Opera Bastille in Paris requested that a niqab-wearing spectator - a tourist from the Gulf - should leave the theatre. Without protest, she did. Curiously, the lady in the niqab had to quit a performance of La Traviata: Verdi’s tear-jerker about that earlier category of stigmatised and excluded woman, the courtesan.

In one light, the aggrieved celebrity-hounds outraged that an actor should change her “real” features look like secular fundamentalists. For them, any cosmetic refurbishment, just like the niqab or burka, denies an allegedly authentic self. But we know that the “open” visage also lies. From an early age, we learn that human faces both reveal and conceal. They may be mirrors to the soul or masks of deceit. “There’s no art/ To find the mind’s construction in the face,” laments King Duncan in Macbeth, as he contrasts the duplicitous Thane of Cawdor with the honest looks of Macbeth himself - his future murderer.

This contradiction breeds anxiety - and superstition. The ancient “art” of face-reading sought to guide judgment of character at a time when we knew little or nothing about the background of people with whom we worked, traded or even lived. Face-reading survives, in that netherworld where antediluvian tradition collides with celebrity obsession. A recent book on the “technique” classifies ours phizzogs into wood, metal, water, fire and earth - Renee Zellweger, it seems, has a water face, “flexible, adaptable and good company”. However, in the 19th century, the pseudo-science of “physiognomy” - in effect, an updated version of medieval lore - garnered heavyweight support precisely at the time when mug-shots and measurements sought to define and confine offenders, subversives, “defectives” and other anti-social elements. For the arch-eugenicist Francis Galton, close-up photography could reveal the criminal face.

Nobody credits such bunkum now. One doesn’t have to live too many years on earth to run across the choirboy-featured thug, the baby-faced schemer and the sweet, kind angel who resembles a wasp-chewing mastiff. Yet still we scan features for evidence of frankness or deceit. Anyone cheered by the rough sleeper who tells you (as he does everyone) that you have a “kind face” after dropping a few coins lives partly in the Middle Ages. That means all of us.

So facial features modified by medicine, art or fashion can still arouse suspicion. The mistake lies in a confusion between alteration and dissimulation. A face can be a work of art that tells the truth. No acclaimed truth-teller ever looked more proudly unimproved than George Orwell, who wrote on his deathbed that “At fifty, every man has the face he deserves”. Orwell really was the man you see in the pictures, that tweed-clad granitic pillar of bloody-minded courage and integrity. Yet self-fashioning, chosen experience and sheer willpower had helped him look like that. True to his dictum, Orwell made his own face almost as much as Renee Zellweger has made hers.

Even the most straightforward visage may seek to twist our arm or change our mind. When Oliver Cromwell commissioned the famous “warts and all” portrait from Samuel Cooper, he knew full well it could boost his image. When you trade in rugged austerity, then blemishes bring benefits. Look at the 500-year history of self-portraiture in Western art and you grasp that the most unflinching analytic gaze cast by artists on their wrinkles, bulges, lines, scars and bags can amount to a kind of self-dramatisation. Haggard, drawn or puffy, on the far edge of age, exhaustion or anxiety, a Rembrandt, Munch or Van Gogh will still always act the star on the great stage of life.

In his excellent new survey of the genre (The Self-Portrait: a cultural history), the critic James Hall points out that Rembrandt’s 1665 self-portrait - one of more than 40 he drew or painted, and now at Kenwood House in London - depicts the artist not just as a flabby, rubicund old man but a “grandiose and heroic” figure. For Hall, Rembrandt’s self-representations “created his fame as much as they reflected it”. Faces need not be smooth, bland or pretty to celebrate, and market, their owners.

Equally, the face - especially for modern women artists - may be the least revealing dimension of autobiographical or confessional work. Hall remarks that, in Frida Kahlo’s many self-portraits, her “expressionless, mask-like face surmounts a body to which many things can and do happen - mostly involving suffering”. More recently, the photo-artist Cindy Sherman has transformed her own features into a spectrum of looks - many taken from movie or magazine stereotypes - in haunting tableaux. Their candour and insight about femininity and its discontents have nothing to do with putting on a “natural” face.

Thanks to the ubiquitous “selfie”, we can all be self-portraitists now. But such constant access to our own physiognomies ought to show how plastic and malleable our features are. Even without “a trace of make-up” (as those old hairspray ads put it) or the touch of a chemical-filled syringe, faces may mutate along with moods, day by day or hour by hour. Rather than denounce Zellweger on the suspicion of having “work” done, the looks police ought to glance in the mirror. We all do work on our faces. And that work is our ever-changing self.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies